Independent Directors in India: Comprehensive guide to roles, eligibility criteria, responsibilities, compensation, liability framework, committee functions under Companies Act 2013 & SEBI regulations.

Table of Contents

Independent directors serve as the cornerstone of robust corporate governance in Indian companies.

These non-executive board members bring objectivity, expertise, and impartiality to boardroom deliberations, acting as safeguards for minority shareholders while ensuring companies operate within ethical and legal boundaries.

Under the Companies Act, 2013, independent directors have emerged as critical gatekeepers who balance the interests of management, shareholders, and other stakeholders.

This comprehensive guide explores everything you need to know about independent directors in India—from their legal definition and eligibility criteria to their roles, responsibilities, compensation structure, and liability framework.

What does one mean by Independent Director?

An independent director is fundamentally a non-executive board member who maintains complete independence from the company’s management, promoters, and substantial shareholders.

Unlike executive directors who are involved in day-to-day operations, independent directors provide oversight, strategic guidance, and objective evaluation from an arm’s length position.

Their independence is not merely a label but a legally defined status backed by specific criteria that ensure they remain free from conflicts of interest.

The concept of independent directors gained prominence in India following corporate governance scandals like Satyam Computer Services, which exposed the need for stronger checks and balances within boardrooms.

Today, independent directors serve as the “conscience keepers” of companies, bringing external perspectives, industry expertise, and unbiased judgment to critical decisions involving strategy, risk management, financial reporting, and executive compensation.

They act as mediators between management and shareholders, ensuring that corporate actions serve the long-term interests of all stakeholders rather than benefiting a select few.

Definition under section 149(6) of the Companies Act, 2013

Section 149(6) of the Companies Act, 2013 provides a comprehensive definition of an independent director through a series of negative conditions.

According to this provision, an independent director means a director other than a managing director, whole-time director, or nominee director who, in the board’s opinion, is a person of integrity and possesses relevant expertise and experience.

The law then specifies what an independent director must not be or have been, creating a framework of disqualifications designed to ensure true independence.

The definition emphasizes several core requirements that collectively define independence.

First, the person should not be or have been a promoter of the company or its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies.

Second, they should not be related to promoters or directors in the company or its group entities.

Third, the person should not have or have had any pecuniary relationship with the company exceeding 10% of their total income or as prescribed, during the two immediately preceding financial years or the current financial year.

These restrictions ensure that independent directors maintain objective judgment unclouded by financial dependencies or personal relationships.

Additionally, the definition lays down other certain that helps in determining independence, these criterias are dealt in detail in the later part. Bottom line is these provisions under section 149(6) collectively create a robust framework ensuring that independent directors truly operate independent of management influence.

Key characteristics that define independence

True independence in the context of directorship encompasses several dimensions beyond mere compliance with statutory criteria.

The primary characteristic is impartiality in judgment—independent directors must evaluate situations objectively without bias toward management, controlling shareholders, or any particular stakeholder group. This impartiality allows them to ask difficult questions, challenge assumptions, and provide candid feedback even when it conflicts with management’s proposals. They must resist pressures from promoters or executives and prioritize the company’s long-term interests over short-term gains or personal relationships.

Another defining characteristic is financial independence.

Independent directors should not derive significant income from the company beyond what is allowed in the law, ensuring their financial well-being doesn’t depend on maintaining good relations with management. This financial autonomy enables them to take unpopular stands when necessary, oppose questionable transactions, and if needed, resign rather than compromise their principles. The prohibition on stock options for independent directors under Section 149(9) further reinforces this principle, preventing their interests from becoming too closely aligned with short-term stock price movements.

Professional expertise and experience constitute the third pillar of independence. Independent directors are expected to bring specialized knowledge in areas like finance, law, technology, or industry-specific domains that complement the board’s collective capabilities. This expertise gives them the credibility and confidence to question management decisions, evaluate complex proposals, and contribute meaningfully to strategic discussions. Their external perspective, often shaped by experience across multiple organizations, helps boards avoid groupthink and consider alternatives that insiders might overlook.

Finally, ethical integrity and reputation form the foundation of an independent director’s value proposition. These directors must demonstrate high moral standards, transparency in their dealings, and commitment to good governance practices. They should have no history of fraudulent activities, regulatory violations, or conflicts of interest that could undermine stakeholder confidence. This reputational capital allows them to serve as credible voices for shareholders, particularly minority investors who may lack direct influence over company affairs.

Difference between Independent Director vs. Non-Executive Director vs. Executive Director

The Indian corporate governance framework recognizes three distinct categories of directors, each with different roles, powers, and obligations.

Executive Directors are actively involved in the company’s management and operations. They typically hold positions like

- Managing Director (MD),

- Whole-Time Director (WTD), or

- Chief Executive Officer (CEO).

These directors receive monthly salaries, participate in day-to-day decision-making, implement board policies, and are accountable for operational performance.

Their compensation is often linked to company performance through bonuses, profit-sharing, and stock options. Executive directors have the highest level of information access and control over company affairs but also face the greatest scrutiny for operational failures.

Non-Executive Directors (NEDs) do not participate in daily management but attend board meetings to provide guidance and oversight.

They may have relationships with the company through shareholding, prior employment, or business connections that would disqualify them from being classified as independent. NEDs can be promoter representatives, investor nominees, or individuals with strategic interests in the company. They receive sitting fees and may receive profit-linked commission similar to independent directors. The key distinction is that NEDs need not meet the strict independence criteria specified in Section 149(6). For example, a venture capital investor’s nominee on a startup board would be a non-executive director but not an independent director due to the material financial relationship.

Independent Directors (IDs) represent a specialized subset of non-executive directors who meet all the negative criteria specified in Section 149(6) and maintain complete independence from the company, its management, and substantial shareholders. They cannot hold more than 2% voting power, should have no pecuniary relationships exceeding prescribed limits, and must not be related to promoters or directors. Independent directors are specifically mandated for certain board committees like the Audit Committee (must form two-thirds) and Nomination & Remuneration Committee (must form at least half). They cannot receive stock options under Section 149(9), unlike other non-executive directors.

The liability framework also differs significantly across these categories. While executive directors can be held liable for operational decisions and day-to-day management failures, independent directors enjoy limited liability under Section 149(12). They are only liable for acts of omission or commission that occurred with their knowledge (attributable through board processes), consent, or connivance, or where they failed to act diligently.

This protection recognizes that independent directors, unlike executive directors, lack access to complete operational information and do not control daily business activities. Non-executive directors who are not independent fall somewhere in between—they may face greater liability than independent directors but less than executive directors, depending on their level of involvement and knowledge.

From a tenure perspective, executive directors and non-executive directors are subject to retirement by rotation under Section 152 of the Companies Act, whereas independent directors are explicitly exempted from this requirement.

Independent directors serve fixed terms of up to five consecutive years and can be reappointed for another five-year term only through special resolution. Executive directors typically have longer continuous tenures without mandatory rotation, while other non-executive directors must retire by rotation as per statutory requirements. These distinctions in appointment, tenure, compensation, and liability reflect the unique governance role that independent directors play in balancing management power and protecting stakeholder interests.

What are the eligibility and disqualification criteria for independent directors?

The appointment of independent directors is governed by stringent eligibility requirements designed to ensure that only qualified, ethical, and truly independent individuals serve in these critical positions. The Companies Act, 2013, and SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 establish both positive eligibility criteria—qualities that candidates must possess—and negative criteria—circumstances that disqualify individuals from serving as independent directors. This dual framework ensures that independent directors bring value to the board while remaining free from conflicts that could compromise their objectivity.

Understanding these criteria is essential for both companies seeking to appoint independent directors and professionals aspiring to these positions. The eligibility requirements focus on integrity, expertise, and professional standing, while disqualification provisions address relationships, financial interests, and past conduct that could undermine independence. Together, these provisions create a comprehensive screening mechanism that upholds the integrity of India’s corporate governance framework.

Who can be appointed as an Independent Director?

Integrity, Expertise and Qualification Requirements

The foremost requirement for an independent director is that they must be a person of integrity, as assessed by the board of directors. This integrity requirement is subjective yet fundamental—it encompasses honesty, ethical conduct, professional reputation, and a track record of principled decision-making.

Boards evaluate integrity through background checks, reference verification, and assessment of the candidate’s professional history for any instances of fraud, misconduct, or regulatory violations. A person with questionable ethical standards, regardless of their professional qualifications, cannot serve effectively as an independent director.

Relevant expertise and experience constitute the second pillar of eligibility.

Independent directors must possess specialized knowledge in one or more fields such as finance, law, management, marketing, technology, operations, or other disciplines relevant to the company’s business. This expertise requirement ensures that independent directors can meaningfully contribute to board deliberations rather than merely rubber-stamping management proposals. For instance, a technology company would benefit from independent directors with experience in software development, cybersecurity, or digital transformation, while a pharmaceutical company might seek directors with regulatory affairs or clinical research backgrounds.

Professional qualifications further strengthen an independent director’s credibility and effectiveness. While the law doesn’t mandate specific degrees or certifications, directors with professional credentials—such as Chartered Accountants, Company Secretaries, lawyers, engineers, or MBA degrees—bring structured analytical frameworks and industry knowledge to their roles.

Many independent directors are former CEOs, CFOs, or senior executives who can leverage their leadership experience to guide current management.

Age and Professional Considerations

The Companies Act, 2013 does not specify a minimum age for appointment as an independent director. However, this is largely academic since independent directors are expected to bring substantial professional experience and expertise, which typically requires decades of career development.

In practice, most independent directors are senior professionals in their 40s, 50s, or 60s who have accumulated the knowledge, reputation, and networks that make them valuable board members. Early-career professionals, despite being legally eligible, rarely possess the gravitas or experience necessary to effectively challenge management or guide corporate strategy.

The SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 impose additional age restrictions for listed companies.

The minimum age is 21 years as per Regulation 16, and the maximum age is 75 years as per Regulation 17 of the (Listing Obligation and Disclosure Requirement). If you are above 75 years old, your appointment requires approval by a special resolution from shareholders, along with an explanatory statement justifying why your age shouldn’t disqualify you.

This upper age limit recognizes that while experience is valuable, boards also benefit from fresh perspectives and the energy that younger directors can bring to oversight roles.

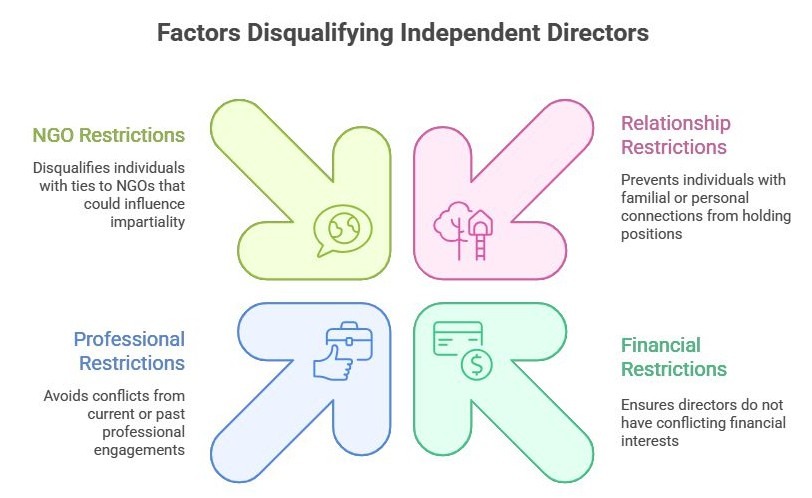

Who Cannot Be an Independent Director? (Negative Criteria)

Under Section 149(6) of the Companies Act

Section 149(6) establishes comprehensive negative criteria that disqualify individuals from serving as independent directors.

Relationship restrictions

The independence principle fundamentally requires separation from company control structures and decision-makers. These relationship-based restrictions ensure you maintain objectivity.

Cannot Be a Promoter of the Company or Its Group

If you’re a promoter—someone who founded the company, controls its management, or holds substantial equity—you cannot serve as an independent director. This extends beyond just the company itself to its holding, subsidiary, and associate companies.

The logic is straightforward.

Promoters have vested interests in the company’s success and typically significant financial stakes. Appointing a promoter as an independent director would defeat the purpose of having independent oversight, as you could not objectively evaluate management decisions when you are part of the management control group.

Cannot Be Related to the Promoters/Directors of the Company or Its Group

Relationship restrictions go beyond direct promoter status.

If you are related to promoters or directors of the company, its holding company, subsidiary, or associate company, you are disqualified.

“Related” here means close family relationships as defined under section 2(77) the Companies Act: spouse, parent, brother, sister, and children, etc.

This restriction prevents family networks from circumventing independence requirements.

Imagine if a promoter’s brother-in-law served as an independent director—would that person truly provide independent oversight, or would family loyalty influence their judgment?

The law eliminates this ambiguity by prohibiting such appointments entirely.

Financial & shareholding restrictions

Financial relationships compromise independence by creating economic dependencies that could influence your judgment. The law sets specific thresholds to maintain your economic independence.

No Material Pecuniary Relationship with the Company/Group/Promoter or Director Beyond a Limit

You cannot have a material pecuniary relationship with the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies, or their promoters or directors, during the current financial year or the two immediately preceding financial years. “Material pecuniary relationship” means financial transactions exceeding 10% of your total income or such higher amount as prescribed.

What does this mean practically?

If you are a consultant earning ₹20 lakhs annually and ABC Ltd. pays you ₹3 lakhs for consulting services, that is 15% of your income—a material pecuniary relationship that disqualifies you from being an independent director of ABC Ltd.

However, receiving sitting fees and commission as an independent director doesn’t count as a pecuniary relationship—that’s specifically permitted remuneration.

No Relative to Hold ≥2% Voting Power in the Company or Group

If your relatives hold 2% or more of the company’s voting power (either individually or together), you are disqualified. This rule extends to the company’s holding, subsidiary, and associate companies.

Here’s why this matters: A relative with 2% voting power has meaningful influence over shareholder resolutions. If your spouse or parent holds significant shares, their financial interest could unconsciously bias your board decisions, even if you believe you are acting independently.

Restrictions relating to relatives of independent directors

The restrictions extend beyond your own financial relationships to those of your relatives, recognizing that family financial interests can compromise your independence just as effectively as your own.

Holding Securities Above the Threshold

Your relatives cannot hold or have held 2% or more of the company’s total voting power during the current financial year or the two immediately preceding financial years. This is the mirror provision of the previous restriction—it focuses on your relatives’ shareholdings rather than your relationship to shareholders.

Indebtedness to the Company/Group/Promoters/Directors

Your relatives cannot be indebted to the company, its subsidiary, holding, or associate company, or their promoters or directors. Even indirect indebtedness through a third party creates a disqualification.

This prevents scenarios where a company provides loans or credit facilities to your family members, creating obligations that could influence your independent judgment when evaluating management proposals or financial decisions.

Guarantees/Security for the Indebtedness of Others

Your relatives cannot have provided guarantees or security in connection with third-party indebtedness to the company or its group companies, promoters, or directors, exceeding ₹50 lakhs at any time during the two immediately preceding financial years or during the current financial year.

This restriction might seem obscure, but it prevents indirect financial entanglements. If your brother guaranteed a ₹1 crore loan that a supplier took from the company, that financial connection could compromise your independence when evaluating the supplier relationship or loan terms.

Pecuniary Transactions ≥2% of Turnover/Income

Your relatives cannot have had any other pecuniary transaction or relationship with the company, or its subsidiary, or its holding or associate company amounting to two per cent. or more of its gross turnover or total income, singly or in combination with the transactions referred to in sub-clause (i), (ii) or (iii) stated above, during the current financial year or the two immediately preceding financial years.

Suppose XYZ Ltd. has a gross turnover of ₹500 crore. Two per cent of its turnover is ₹10 crore.

If the spouse of an independent director runs a consulting firm that earns ₹12 crore from XYZ Ltd. during the financial year — whether through a single contract or multiple smaller transactions — this would cross the 2% pecuniary transaction threshold.

Even though the independent director personally has no direct financial dealing with XYZ Ltd., the relative’s substantial business with the company would compromise the director’s independence, making them ineligible to serve as an independent director under Section 149(6)(iv) of the Companies Act, 2013.

Professional and employment restriction

Past professional and employment relationships create potential conflicts even after they have ended, so the law mandates cooling-off periods.

Past 3 Years as KMP/Employee of Company or Group

If you were a Key Managerial Personnel (KMP) or employee of the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate company within the three immediately preceding financial years, you’re disqualified. KMPs include the CEO, Managing Director, CFO, Company Secretary, and Whole-time Director.

This three-year cooling-off period ensures you have developed sufficient separation from management thinking. If you were the CFO until two years ago, your recent involvement in financial decisions could bias your supposedly independent evaluation of those same financial matters.

Partner/Proprietor/Employee (Past 3 Years) of Specified Service Providers

You cannot have been, within the three immediately preceding financial years, a partner, proprietor, or employee of firms providing specific professional services to the company or its group:

- statutory audit firms,

- internal audit firms,

- cost audit firms,

- legal firms, or

- consulting firms receiving 10% or more of their gross turnover from the company or its group.

This restriction prevents potential conflicts from recent professional service relationships.

If your law firm earned substantial fees from ABC Ltd. until two years ago, you might find it difficult to objectively evaluate legal matters or challenge management decisions that benefited your former firm.

The 10% threshold for consulting and legal firms recognizes that some professional contact is inevitable, but substantial economic dependence creates disqualifying conflicts. If the company represented only 5% of your firm’s revenue, that’s permitted; if it represented 15%, you’re disqualified.

NGO restriction

Even seemingly benign relationships through non-profit organizations can compromise independence if financial dependencies exist.

CEO/Director of NGO Receiving ≥25% Funds from Company/Group/ Promoters or Holding ≥2% Voting Power

If you are the Chief Executive or Director of a non-profit organization that receives 25% or more of its receipts from the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies, or their promoters or directors, or if the company holds 2% or more voting power in that NGO, you are disqualified.

This rule recognizes that NGOs dependent on corporate funding might face pressure to align with corporate interests.

If you lead an NGO that receives ₹50 lakhs annually from ABC Ltd., comprising 30% of your NGO’s total funding, your independence as an ABC Ltd. board member would be questionable—you might hesitate to challenge decisions if you feared jeopardizing your NGO’s funding.

Disqualification under Section 164 of the Companies Act

Beyond independence-specific restrictions, general director disqualifications under the Companies Act apply to independent directors as well.

Section 164 of the Companies Act, 2013 sets out the circumstances under which a person becomes ineligible to be appointed as a director, including as an independent director. The provision aims to ensure that only individuals with integrity, sound financial standing, and a clean compliance record can hold directorship positions.

Personal and legal disqualifications

A person shall not be eligible for appointment as a director if they:

- Are of unsound mind and have been so declared by a competent court;

- Are an undischarged insolvent;

- Have applied to be adjudicated as an insolvent and the application is pending;

- Have been convicted by a court of any offence and sentenced to imprisonment for a period of at least six months, and five years have not elapsed since the expiry of the sentence;

- Have been convicted of an offence and sentenced to imprisonment for a period of seven years or more (in which case the person is permanently disqualified from being appointed as a director in any company); or

- Have been disqualified by an order of a court or tribunal which remains in force.

Financial and compliance disqualifications

A person also stands disqualified if they:

- Have failed to pay any call money on shares held by them, whether alone or jointly with others, for a period of six months from the last day fixed for payment;

- Have been convicted of an offence relating to related party transactions under Section 188 during the last five years;

- Have not obtained a valid Director Identification Number (DIN) or have not complied with Section 152(3); or

- Have not complied with the provisions of Section 165(1) regarding the maximum number of directorships permissible.

Company-level disqualifications

A person who is or has been a director of a company that:

- Has not filed its financial statements or annual returns for any continuous period of three financial years; or

- Has failed to repay deposits, redeem debentures, or pay interest or dividends for one year or more,

shall be ineligible to be reappointed as a director in that company or appointed in any other company for a period of five years from the date of such default.

However, a person appointed as a director in a defaulting company will not incur the disqualification for a period of six months from the date of their appointment.

4. Additional disqualifications by private companies

Section 164(3) also empowers private companies to prescribe additional disqualifications for directors in their Articles of Association, over and above those provided under the Act.

In essence, Section 164 establishes a comprehensive framework to ensure that individuals who have demonstrated financial impropriety, non-compliance, or lack of integrity are prevented from occupying board positions. It acts as a safeguard to promote transparency, accountability, and good governance in corporate management.

Disqualification under Section 165 of the Companies Act

Section 165 limits the number of directorships you can hold concurrently.

You cannot be a director in more than 20 companies at a time, with a sub-limit of 10 public companies.

However, for independent directors specifically, a more restrictive limit applies: you cannot be an independent director in more than 7 listed companies simultaneously in terms of Regulation 17A of SEBI (LODR).

If you are already a whole-time director in any listed company, your independent directorship limit drops to 3 listed companies. These restrictions ensure you have sufficient time and attention to devote to each directorship, preventing overextension that could compromise your effectiveness.

Disqualification under SEBI LODR

The SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 impose similar disqualification criteria for independent directors of listed companies under Regulation 16(1)(b).

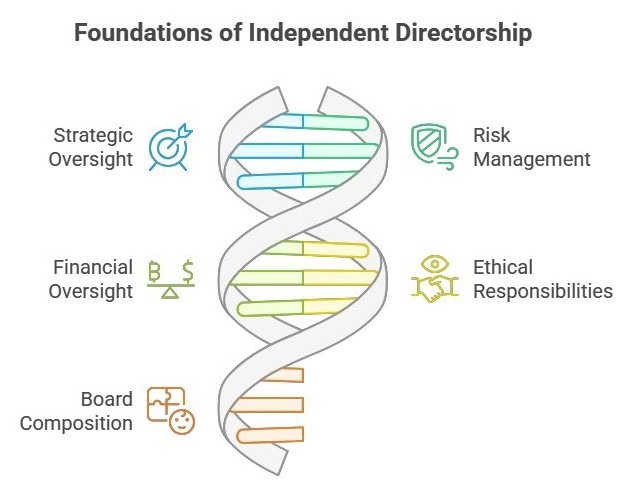

What are the roles and responsibilities of independent directors?

Independent directors discharge multifaceted responsibilities that span strategic guidance, financial oversight, stakeholder protection, and ethical governance.

Their roles are defined by the Companies Act, 2013 (particularly Schedule IV), SEBI Regulations, and evolving judicial interpretations that have clarified the scope and limits of their duties.

The responsibilities of independent directors extend beyond passive attendance at board meetings.

They must actively engage with company information, seek clarifications when necessary, monitor management performance against agreed objectives, and intervene when they detect governance lapses or ethical violations. Schedule IV of the Companies Act specifies that independent directors should help bring independent judgment to the board’s deliberations, particularly on strategy, performance, risk management, resources, key appointments, and standards of conduct.

This active engagement requirement distinguishes effective independent directors from token appointees who merely lend their names to company letterheads without substantive involvement.

Strategic and governance oversight

Independent directors provide objective judgment on the company’s strategic direction. They assess whether management’s plans align with long-term value creation, not short-term gains. This includes scrutinizing assumptions behind major initiatives such as acquisitions, expansions, and capital expenditures to ensure that risks and returns are balanced.

Their governance role also involves establishing performance expectations and holding management accountable through clearly defined KPIs. They evaluate both financial and operational performance, seeking explanations for deviations and ensuring that corrective actions are taken when goals are missed.

Further, independent directors ensure the presence of robust internal control systems — mechanisms to prevent fraud, detect errors, and ensure compliance with laws and regulations. Oversight of internal audit findings, data security, and remediation actions forms part of this responsibility.

Risk management and executive oversight

Independent directors are guardians against excessive or mismanaged risk. They must ensure that the company identifies and mitigates risks across strategic, financial, operational, and reputational dimensions. Their task is to test management’s risk appetite — avoiding both reckless exposure and excessive conservatism.

A crucial aspect is the evaluation of top executives. Independent directors appraise the performance of the CEO, managing director, and senior leaders against agreed objectives, combining quantitative results with qualitative factors like leadership, ethics, and stakeholder management. Maintaining professional distance enables them to give candid feedback and recommend leadership changes when required.

Financial and audit oversight

Ensuring the integrity of financial statements is one of the most critical board functions. Independent directors review financials before board and shareholder approval, verifying that they reflect a true and fair view of the company’s position. They must understand key accounting policies and estimates, question aggressive recognition practices, and ensure transparent disclosure of contingencies and related-party arrangements.

They also oversee the adequacy of internal financial controls — ensuring proper authorization hierarchies, segregation of duties, and audit mechanisms that prevent misstatements or misuse of assets.

Special vigilance is expected in reviewing related-party transactions (RPTs). Independent directors must ensure that RPTs are at arm’s length, commercially justified, and in the interest of all shareholders.

Stakeholder and ethical responsibilities

Independent directors act as protectors of minority shareholders and other stakeholders who cannot directly influence corporate decisions. They ensure that all board actions are equitable — particularly in matters like related-party transactions, buybacks, and mergers where promoter and minority interests may diverge.

Beyond shareholders, they must balance the expectations of employees, customers, suppliers, and the community. Independent directors are expected to advocate sustainable practices, resisting decisions that boost short-term profits at the cost of ethics, compliance, or social license to operate.

Adherence to Schedule IV of the Companies Act demands integrity, objectivity, and independence. Directors must stay informed, seek clarifications when necessary, and avoid conflicts of interest or misuse of position.

Board composition and remuneration oversight

Independent directors ensure that the board’s structure supports effective governance. This involves identifying gaps in skills and diversity, guiding succession planning, and ensuring the right mix of expertise and independence.

They also determine fair and transparent executive remuneration, linking pay to performance while avoiding excess. Compensation structures should attract talent yet align rewards with long-term shareholder value.

Committee roles

While the substantive roles above define what independent directors must do, committees under SEBI LODR and the Companies Act provide the procedural mechanism through which these roles are executed.

Audit committee (Regulation 18, SEBI LODR)

The audit committee, which must comprise at least two-thirds independent directors, plays the primary role in RPT oversight. As an independent director on this committee, you should establish clear policies defining what constitutes a material RPT requiring board approval, implement robust identification mechanisms to capture all related party relationships, and maintain detailed records of your approval process including the analysis performed and dissent expressed. When RPTs raise concerns about fairness or disclosure adequacy, you must have the courage to reject them or demand modifications, even if this creates tension with promoters or management. This vigilance prevents the tunneling of company resources to related parties, protecting minority shareholder interests. Stakeholder and Ethical Responsibilities

Nomination and remuneration committee (Regulation 19, SEBI LODR)

The Nomination and Remuneration Committee, which must comprise at least three non-executive directors with at least half being independent directors, handles the critical functions of board composition planning, director appointments, executive compensation, and performance evaluation.

As an independent director on this committee, you identify gaps in board skills and competencies, source suitable candidates for director positions, and evaluate their qualifications against predetermined criteria. You must ensure that board composition reflects diversity in skills, experience, gender, and backgrounds, avoiding the tendency toward homogeneity that leads to groupthink. Your recommendations on director appointments shape the board’s collective capabilities and governance effectiveness for years to come.

Executive remuneration represents perhaps the most sensitive committee responsibility, requiring independent directors to balance competing considerations of attracting and retaining talent while preventing excessive pay that enriches management at shareholder expense. You must establish clear remuneration policies linking executive compensation to company performance, recommend appropriate structures combining fixed pay, performance bonuses, and long-term incentives, and set specific compensation levels for the CEO, managing director, and senior executives. Independent directors should benchmark compensation against industry peers while resisting the upward ratchet effect where every company seeks to pay above-market rates. Your oversight ensures that executive pay remains reasonable, transparent, and aligned with shareholder value creation rather than rewarding mediocre performance or creating perverse incentives for excessive risk-taking.

Stakeholders’ relationship committee (Regulation 20, SEBI LODR)

The Stakeholders’ Relationship Committee, which includes at least one independent director, focuses on resolving shareholder grievances and ensuring effective communication with investors. You oversee and addresses shareholder and investor grievances, ensuring fair communication and redressal. May also look at share transfers, dividend payments, and investor correspondence.

Risk management committee (Regulation 21, SEBI LODR)

The Risk Management Committee, mandated for top 1000 listed companies by market capitalization, requires at least one independent director among its members. Here you oversee the company’s risk management framework, evaluate the adequacy of risk identification and mitigation processes, and monitor emerging risks that could threaten business objectives. Your role involves: –

Corporate social responsibility committee (Section 135, Companies Act, 2013)

The Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Committee must include at least one independent director among its three or more members, giving you a voice in how companies fulfill their social obligations. You participate in formulating the CSR policy, which outlines the company’s approach to spending at least 2% of average net profits on specified social, environmental, and economic development activities. Independent directors should ensure that CSR initiatives genuinely address community needs rather than serving as disguised marketing expenses or benefiting related parties. You must monitor project implementation, assess social impact, and ensure transparent reporting of CSR expenditures, intervening when funds are misappropriated or projects fail to deliver intended benefits.

Your committee responsibilities may extend beyond these mandatory committees to include specialized bodies addressing specific governance needs. Many companies establish sustainability committees to oversee environmental, social, and governance (ESG) initiatives, requiring independent directors to evaluate climate risks, diversity metrics, and sustainability reporting. Technology or cybersecurity committees may engage independent directors with relevant expertise to oversee digital transformation initiatives and data protection practices. In each committee context, you bring objective oversight, challenge management assumptions, ensure robust processes, and protect stakeholder interests through vigilant monitoring and constructive engagement.

How long can independent directors serve on a board of directors?

The tenure framework for independent directors balances the benefits of continuity and institutional knowledge against the risks of entrenchment and diminished independence over time.

The Companies Act, 2013 establishes specific term limits, reappointment procedures, and rotation exemptions that govern how long independent directors can serve on boards.

These provisions recognize that while experience enhances an independent director’s effectiveness initially, extended tenures can erode independence as directors develop closer relationships with management, become invested in past decisions, and lose the fresh perspective that makes them valuable.

Understanding tenure rules is essential for both companies planning board succession and independent directors managing their professional commitments. The legal framework attempts to optimize the trade-off between expertise accumulation and independence preservation, while providing flexibility for companies to retain valuable directors through clearly defined reappointment processes.

What are the term limits and reappointment rules?

Independent directors can be appointed for an initial term of up to five consecutive years on the board of a company. This five-year term provides sufficient time for directors to understand the company’s business deeply, build relationships with management and fellow directors, and contribute meaningfully to strategic decisions. The term begins from the date of appointment approved by shareholders in a general meeting and continues until the sixth AGM unless the director resigns, is removed, or becomes disqualified. Unlike executive directors who may have employment contracts spanning decades, independent directors operate under fixed-term appointments that automatically expire without renewal.

Reappointment for a second term requires more stringent approval procedures reflecting heightened scrutiny of continued independence after five years of service. An independent director can be reappointed for one additional term of up to five consecutive years, but only after passing of a special resolution by shareholders in a general meeting as per Section 149(10).

This special resolution requirement (requiring 75% approval) gives minority shareholders greater voice in evaluating whether a director has maintained independence and effectiveness during their first term. The explanatory statement accompanying the resolution must justify the reappointment, typically highlighting the director’s contributions, unique expertise, and continued independence.

After completing two consecutive terms totaling ten years, an independent director cannot continue in that capacity without at least a three-year cooling-off period, though they may serve as a non-executive non-independent director or executive director without such restrictions.

Do rotation requirements apply to independent directors?

Section 149(13) explicitly exempts Independent Director from the retirement by rotation provisions of Section 152 of the Companies Act, 2013.

Under Section 152, at least two-thirds of the total number of directors (excluding independent directors) must be rotational directors who retire at every annual general meeting based on seniority, with one-third retiring annually.

This rotation mechanism ensures periodic shareholder approval of director appointments. However, independent directors were deliberately excluded from this requirement, operating instead under the fixed-term framework described earlier. This exemption recognizes that the special approval processes for independent director appointments, combined with their term limits and special resolution requirements for reappointment, provide adequate shareholder oversight without needing rotation.

The exemption from rotation by requirement provides independent directors with tenure stability during their five-year terms, allowing them to focus on long-term strategic issues without concern about annual shareholder votes. It also simplifies board composition planning since companies can predict when independent director terms will expire based on their appointment dates rather than tracking rotation schedules.

For independent directors, this exemption means you don’t face the annual uncertainty of retirement by rotation, providing clearer visibility into your board tenure. However, you remain subject to the maximum term limits and reappointment procedures specific to independent directors, which ultimately impose stricter tenure restrictions than the rotation requirements applicable to other non-executive directors.

Can an independent director resign or be removed?

Independent directors possess the right to resign from their positions at any time by submitting written notice to the company.

When you decide to resign, you should provide reasonable notice—typically 30 to 90 days—allowing the company time to identify and appoint a replacement.

Your resignation letter should be addressed to the board of directors or the chairperson, and the company must file the requisite form (DIR-11) with the Registrar of Companies within 30 days of receiving your resignation.

While you’re not legally required to provide detailed reasons for resignation, it’s good practice to explain your decision, particularly if you’re resigning due to governance concerns, ethical disagreements, or loss of confidence in management. Such explanations create a record that may protect you from future liability allegations.

Removal of an independent director before term completion is possible but requires following stringent procedures that protect directors from arbitrary dismissal.

The company must pass an ordinary resolution in a general meeting to remove any director, including independent directors, before their term expires. However, the director must receive reasonable opportunity to be heard, either personally or through a representative, at the meeting where removal is being considered. In practice, removal of independent directors is relatively rare because it signals governance problems and may damage the company’s reputation with investors and regulators.

How are independent directors compensated in India?

Independent directors in India are compensated primarily through sitting fees for attending board and committee meetings, and in some cases, through profit-linked commissions when the company records profits. Their remuneration structure reflects their part-time advisory role, unlike executive directors who draw fixed monthly salaries and benefits.

Sitting fees under section 197(5)

Under Section 197(5) of the Companies Act, 2013, independent directors may receive sitting fees for attending meetings of the board or any of its committees. Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Remuneration of Managerial Personnel) Rules, 2014 caps such fees at ₹1,00,000 per meeting, though boards may fix lower amounts based on company size and financial strength.

The sitting-fee mechanism incentivizes directors to attend and contribute meaningfully to board deliberations. It also recognizes the significant time independent directors spend reviewing board papers, engaging with management, and participating in committee work. Many large listed companies pay the maximum permissible amount, while smaller companies typically pay less.

Profit-linked commission under section 198

In addition to sitting fees, independent directors may receive a commission on profits calculated under Section 198 of the Act.

- The aggregate commission payable to all non-executive directors cannot exceed 1% of net profits if the company has a managing or whole-time director, or 3% otherwise.

- Distribution among directors generally depends on committee memberships, attendance, and special contributions, as recommended by the Nomination and Remuneration Committee (NRC) and approved by the board.

Profit-linked commissions aim to align directors’ interests with company performance, but critics caution that they may encourage an excessive focus on short-term profitability at the expense of independent oversight.

Minimum remuneration during loss periods — companies (amendment) act, 2020

The Companies (Amendment) Act, 2020 resolved a long-standing anomaly where independent directors in loss-making companies were eligible only for sitting fees, while executive directors could still draw remuneration under Schedule V.

A proviso to Section 149(9) now allows payment of minimum remuneration to independent directors during periods of no profits or inadequate profits, within Schedule V limits. The ceiling varies by effective capital as follows:Companies may exceed these limits through a special resolution, ensuring flexibility while maintaining shareholder oversight.

This reform ensures that independent directors receive equitable compensation even in financially challenging years, acknowledging the continuity of their fiduciary duties irrespective of profitability.

What is the liability framework and legal protection for independent directors

The liability framework for independent directors represents a delicate balance between accountability and protection, recognizing that these non-executive directors lack day-to-day operational control while still bearing responsibility for governance oversight.

Unlike executive directors who can be held liable for operational decisions, independent directors benefit from statutory protections limiting their exposure to liabilities arising from acts or omissions they didn’t know about, consent to, or participate in. However, these protections aren’t absolute—independent directors who fail to act diligently, ignore red flags, or rubber-stamp management decisions can still face civil and criminal consequences.

The evolution of independent director liability in India reflects tensions between competing policy objectives.

On one hand, stringent liability encourages vigilant oversight and deters token appointments of prominent individuals who lend their names without substantive engagement. On the other hand, excessive liability discourages qualified professionals from accepting board positions, as evidenced by the surge in independent director resignations following high-profile corporate scandals.

Limited liability under section 149(12)

Section 149(12) of the Companies Act, 2013 provides crucial statutory protection limiting independent director liability.

This provision states that an independent director or non-executive director shall be held liable only in respect of acts of omission or commission by a company which occurred with their knowledge, attributable through board processes, and with their consent or connivance, or where they had not acted diligently.

This three-pronged test establishes that for independent director liability to attach, there must be:

(1) knowledge of the act or omission attributable through board processes,

(2) consent or connivance in the wrongful act, or

(3) failure to act diligently despite knowledge.

The “knowledge attributable through board processes” element is particularly important because it limits independent director liability to matters that came before the board or its committees rather than operational issues handled by management without board involvement.

If management engages in wrongdoing without informing the board, independent directors generally aren’t liable unless they should have discovered the misconduct through diligent oversight. This protection recognizes the information asymmetry between independent directors who attend periodic board meetings and management who control daily operations and information flows. However, the “failure to act diligently” exception means you can’t simply claim ignorance—you must actively engage with available information, ask probing questions when issues arise, and ensure adequate monitoring systems exist.

Practical risk mitigation strategies

Pre-appointment due diligence checklist

Before accepting an independent directorship, you should conduct thorough due diligence to understand the risks and responsibilities you’re assuming.

Start by reviewing the company’s financial statements for at least the past three years, examining trends in revenue, profitability, debt levels, and cash flows.

Look for red flags like frequent restatements, qualified audit opinions, significant related party transactions, or unusual accounting treatments that might indicate aggressive financial reporting or governance weaknesses. Request access to recent board minutes to understand the nature of discussions, quality of information provided to directors, and whether independent directors actively participate or merely rubber-stamp management proposals.

Investigate the company’s regulatory compliance record by checking for past penalties, ongoing investigations, or litigation involving the company, its promoters, or management.

Review the composition of the existing board, assessing whether other independent directors have strong reputations and relevant expertise that would support effective governance. Evaluate the company’s business model, competitive position, and strategic challenges to determine whether you possess the industry knowledge necessary to contribute meaningfully. This upfront investment in due diligence helps you make informed decisions about whether to accept board positions and negotiate appropriate terms.

Meeting documentation and whistleblower mechanisms

Once appointed as an independent director, meticulous documentation of your participation, questions raised, and dissent expressed becomes your primary liability protection.

Always ensure that board and committee meeting minutes accurately reflect your attendance, the issues you raised, concerns you expressed, and positions you took on controversial matters. When you disagree with board decisions, insist that your dissent be recorded in the minutes rather than remaining silent. If the board approves actions despite your opposition, your recorded dissent demonstrates that you fulfilled your oversight responsibility and didn’t consent to or connive in potentially problematic decisions.

Whistleblower mechanisms and vigil committees provide independent directors with additional tools for risk mitigation.

You must ensure that the company maintains a functional whistleblower policy allowing employees, customers, and other stakeholders to report concerns about unethical conduct, fraud, or legal violations.

As an independent director, you should review whistleblower complaints received, ensure they’re investigated thoroughly and independently, and protect complainants from retaliation. The vigil committee, typically chaired by an independent director, oversees these processes. Active engagement with whistleblower mechanisms helps you detect problems early, before they escalate into major scandals that could expose you to liability while demonstrating your commitment to diligent oversight.

D&O insurance considerations

Directors and Officers (D&O) insurance provides financial protection against legal costs and liability awards arising from your service as an independent director. These policies typically cover legal defense expenses even if allegations prove unfounded, protecting your personal assets from depletion due to protracted litigation.

When evaluating board opportunities, you should verify that the company maintains adequate D&O insurance coverage with reputable insurers, ensuring policy limits are sufficient to cover potential claims given the company’s size, industry, and risk profile. The policy should cover independent directors individually (not just the company or management) and include advancement provisions that pay defense costs as incurred rather than only after final judgments.

However, D&O insurance isn’t a panacea—policies typically exclude coverage for fraud, deliberate wrongdoing, personal profit, and criminal fines. If you knowingly participate in misconduct or fail to exercise basic diligence, insurance likely won’t protect you. Additionally, Indian insurance regulations and policy terms may limit coverage for certain regulatory actions or penalties.

Therefore, while D&O insurance is a valuable risk mitigation tool, it complements rather than substitutes for diligent discharge of your oversight responsibilities. You should review policy terms carefully, understand coverage limitations, and factor insurance adequacy into your decision about accepting board positions.

Conclusion

By now, you’ve seen the full picture — who an Independent Director is, what qualifies (and disqualifies) them, their roles, duties, liabilities, and the fine balance they must maintain between guidance and governance.

But understanding what makes an independent director is only half the story. The real challenge lies in being one — in practicing independence not just in designation, but in thought, action, and principle.

True independence is tested when difficult decisions arise, when management pressures mount, or when silence feels safer than dissent. That’s where an Independent Director proves their worth — not as a statutory appointee, but as the company’s ethical guardrail.

As India’s corporate governance landscape matures, the future will belong to boards that don’t just include independent directors for compliance, but empower them to speak, question, and act without fear. Because independence, in the truest sense, isn’t granted by law — it’s earned through integrity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a practising Company Secretary be appointed as an Independent Director?

Yes, a practicing Company Secretary can be appointed as an independent director since it is a non-executive position that doesn’t conflict with professional practice obligations. However, they cannot serve as independent director in a company where they provide professional services as a company secretary.

What is the maximum tenure for an Independent Director in India?

An independent director can serve a maximum of two consecutive terms of five years each, totaling ten years. After completing two terms, they must observe a three-year cooling-off period before being eligible for reappointment as an independent director.

Can an Independent Director receive monthly remuneration like Executive Directors?

No, independent directors cannot receive monthly salaries like executive directors. They can only receive sitting fees (up to ₹1 lakh per meeting), profit-linked commission, and minimum remuneration as per Schedule V during loss periods, but not regular monthly compensation.

Is an Independent Director liable for day-to-day operations of the company?

No, Section 149(12) limits independent director liability to acts occurring with their knowledge through board processes, with their consent or connivance, or where they failed to act diligently. They’re not liable for operational matters handled by management without board involvement.

What is the difference between Independent Director and Non-Executive Director?

While both are non-executive, independent directors must meet specific independence criteria under Section 149(6) including no material relationships with the company, promoters, or management. Non-executive directors may have such relationships, like being nominee directors representing investors, without meeting independence requirements.

How many board meetings must an Independent Director attend annually?

While there’s no statutory minimum specifically for independent directors, companies must hold at least four board meetings annually with maximum gaps of 120 days. Independent directors should strive to attend all meetings to fulfill their oversight responsibilities effectively.

Can an Independent Director be removed before completing the term?

Yes, independent directors can be removed through an ordinary resolution passed in a general meeting before their term expires. However, they must be given reasonable opportunity to be heard at the meeting, and removal signals potential governance concerns.

What happens if an Independent Director loses independence during the term?

An independent director who loses independence due to changed circumstances must immediately inform the board. They can no longer continue as an independent director but may transition to a non-independent non-executive director role if the company and director agree.

Are Independent Directors required to register with the Independent Directors Databank?

Yes, individuals seeking appointment as independent directors must register with the Independent Directors Databank maintained by the Indian Institute of Corporate Affairs and pass an online proficiency self-assessment test, unless they qualify for exemptions based on prior experience.

What is the sitting fee limit for Independent Directors in India?

The maximum sitting fee for independent directors is ₹1,00,000 per board or committee meeting as per Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Remuneration of Managerial Personnel) Rules, 2014. Companies may pay lower amounts based on their policies.

Can Independent Directors receive Employee Stock Options (ESOPs)?

No, Section 149(9) explicitly prohibits independent directors from receiving stock options. This restriction ensures their independence isn’t compromised by equity holdings that could align their interests too closely with short-term stock price movements rather than long-term governance.

What are the committee responsibilities of Independent Directors?

Independent directors must form at least two-thirds of the Audit Committee and at least half of the Nomination & Remuneration Committee. They serve on CSR, Risk Management, and Stakeholders’ Relationship Committees, providing independent oversight of financial reporting, executive compensation, social responsibility, and stakeholder grievances.

How is Independent Director liability different from Executive Director liability?

Independent directors have limited liability under Section 149(12)—liable only for acts with their knowledge through board processes, consent, connivance, or failure to act diligently. Executive directors face broader liability for operational decisions and management actions due to their day-to-day control.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications