Complete guide to independent director eligibility under Companies Act 2013 & SEBI regulations. Learn Section 149(6) criteria, financial independence requirements, disqualifications & compliance.

Table of Contents

Understanding independent director eligibility is crucial for both aspiring directors and companies seeking to ensure regulatory compliance.

The eligibility framework under Indian corporate law involves a dual regulatory approach—the Companies Act 2013 establishes baseline criteria for all companies, while SEBI’s LODR Regulations impose additional requirements for listed entities.

This comprehensive guide decodes the complex eligibility conditions, financial independence thresholds, professional background restrictions, and legal disqualifications that determine who can serve as an independent director in India.

What constitutes independent director eligibility under the Companies Act and SEBI Regulations?

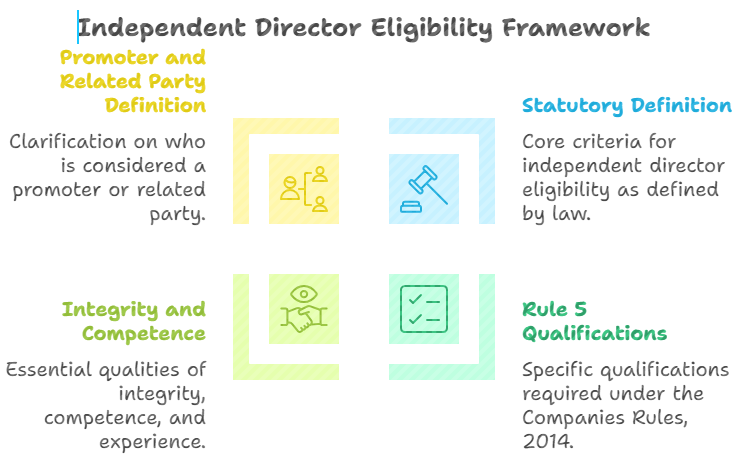

Independent director eligibility in India is governed by two parallel regulatory frameworks that work together to ensure board independence and protect stakeholder interests. The Companies Act 2013 provides the foundational eligibility criteria applicable to all companies requiring independent directors, while SEBI’s Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements (LODR) Regulations add supplementary conditions specifically for listed companies.

Understanding both frameworks is essential because listed company directors must satisfy both sets of requirements simultaneously—failing to meet either disqualifies a candidate from independent directorship.

Definition under section 149(6)

Section 149(6) of the Companies Act 2013 defines an independent director as a non-executive director who is neither a managing director, whole-time director, nor nominee director, and who meets specific independence criteria.

The director must be a person of integrity with relevant expertise and experience, as determined by the board. Critically, the individual cannot be or have been a promoter of the company or its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies, and must not be related to any promoters or directors in the company’s group.

The definition further requires the absence of any pecuniary or material relationships that could compromise independent judgment.

Definition under regulation 16(1)(b) of SEBI LODR

Regulation 16(1)(b) of the SEBI LODR Regulations supplements the Companies Act definition with additional independence criteria specific to listed companies. Under this regulation, an independent director or their relatives must not have business relationships with the company, its subsidiaries, or associates that could materially affect the director’s independent judgment.

The regulation explicitly bars individuals who are material suppliers, service providers, customers, lessors, or lessees of the company.

SEBI’s framework also imposes stricter age limits, cross-directorship restrictions, and enhanced disclosure requirements that go beyond the Companies Act baseline, creating a more stringent eligibility standard for directors of publicly traded companies.

For a more detailed breakdown of the statutory framework, see our dedicated article on independent director under the Companies Act, 2013.

Who qualifies as an independent director under section 149(6) for independent director eligibility?

Section 149(6) establishes a comprehensive eligibility framework built on multiple interdependent criteria that collectively ensure director independence. The provision creates both positive requirements—qualities and qualifications a candidate must possess—and negative restrictions—relationships and connections that disqualify candidacy. This dual approach means aspiring independent directors must not only demonstrate requisite competence and integrity but also prove the absence of any financial, professional, or personal relationships that could compromise their ability to exercise objective judgment in board deliberations.

Statutory definition and core eligibility criteria

The statutory definition under Section 149(6) requires that an independent director must first be a non-executive director who does not participate in the day-to-day management of the company.

The individual must possess integrity, relevant expertise, and experience as assessed by the board of directors during the appointment evaluation. The core eligibility framework prohibits anyone who is or was a promoter of the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies, or who has any direct or indirect relationship with promoters or directors in the company’s group. This foundational criterion ensures that independent directors have no vested interest in the company’s formation, ownership structure, or management hierarchy that could bias their oversight function.

If you’re exploring board roles and want to understand the pathway to appointment, see my step-by-step guide on how to become an independent director.

Qualifications required under rule 5 of the companies (appointment and qualification of directors) rules, 2014

Rule 5 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 operationalizes Section 149(6) by prescribing specific thresholds and clarifications for determining eligibility.

The rule that an independent director shall possess appropriate skills, experience and knowledge in one or more fields of finance, law, management, sales, marketing, administration, research, corporate governance, technical operations or other disciplines related to the company’s business.

The rule establishes that none of the relatives of an independent director can be indebted to the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies, or their promoters or directors for amounts exceeding Rs 50 lakh during the two preceding financial years or current year. Additionally, relatives cannot provide guarantees or security for third-party indebtedness to these entities exceeding Rs 50 lakh during the same period.

These monetary thresholds create clear quantitative benchmarks for assessing whether family relationships create disqualifying financial entanglements with the company.

Integrity, competence, and experience requirements under independent director eligibility norms

The integrity requirement under Section 149(6)(a) mandates that the board must satisfy itself that the proposed independent director is a person of good character and ethical standing.

This subjective assessment requires the board to evaluate the candidate’s professional reputation, track record of ethical conduct, and absence of any criminal convictions or regulatory sanctions that would cast doubt on their moral fitness.

The evaluation should include verification of the candidate’s credentials, reference checks, and review of any past instances of professional misconduct or legal violations.

The competence and experience requirements demand that independent directors possess relevant expertise in one or more fields such as law, finance, management, accounting, taxation, corporate governance, risk management, or other disciplines related to the company’s business operations.

The board must evaluate whether the candidate’s professional background, educational qualifications, and career accomplishments demonstrate sufficient subject matter expertise to contribute meaningfully to board deliberations. This assessment is context-specific—a technology company would value different expertise than a pharmaceutical company—allowing boards to tailor independent director selection to their specific governance needs and industry challenges.

Section 149(8) makes compliance with Schedule IV mandatory for both the company and the independent director, meaning adherence to the code of professional conduct and role expectations is not merely advisory but a statutory requirement.

Who is considered a promoter or related party?

Section 2(69) of the Companies Act 2013 defines a promoter as a person who has been named in a prospectus or identified by the board as someone who controls the company’s affairs, or in accordance with whose advice, directions, or instructions the board is accustomed to act. Promoters typically include the founders, initial shareholders, persons who raise capital or make arrangements for company formation, and those who exercise management control during the company’s formative stages. The prohibition on independent directors being promoters extends to promoters of the company’s holding, subsidiary, and associate companies, ensuring no directional influence from any entity within the corporate group.

Related parties encompass a broader category that includes not just promoters but also their relatives, directors, key managerial personnel, and entities controlled by these individuals. Section 2(76) read with Section 2(77) defines related parties and relatives respectively, creating an extensive network of disqualifying relationships. For independent director eligibility purposes, candidates cannot be related to any directors or promoters in the company, its holding company, subsidiaries, or associate companies through blood relations, marriage, or adoption as specified in Section 2(77). This comprehensive relationship exclusion prevents family networks and personal connections from compromising board independence.

What financial independence conditions are required for independent director eligibility?

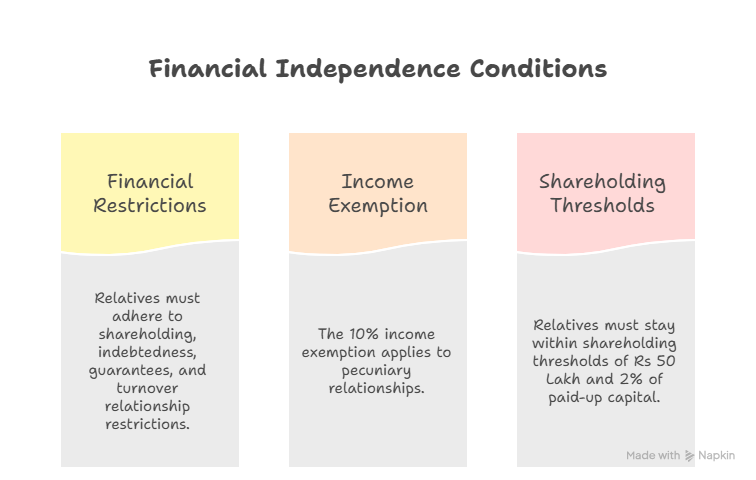

Financial independence forms the cornerstone of independent director eligibility, ensuring that directors have no monetary interests that could bias their judgment or create conflicts of interest. Section 149(6)(c) and (d) establish comprehensive restrictions on pecuniary relationships between the director, their relatives, and the company or its group entities. These financial independence conditions operate on two levels—they regulate both direct financial relationships between the director and the company, and indirect relationships through the director’s family members. The framework recognizes that even family members’ financial stakes can compromise a director’s independence, necessitating strict thresholds for permissible financial connections.

How the 10% income exemption applies to pecuniary relationships

Section 149(6)(c) prohibits independent directors from having any pecuniary relationship with the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies, or their promoters or directors during the two immediately preceding financial years or the current financial year. However, the provision carves out two critical exceptions: remuneration received as a director (sitting fees, profit-linked commission as per Section 197), and transactions not exceeding 10% of the director’s total income. This 10% threshold provides a safe harbor for minor financial dealings that don’t materially affect independence.

The 10% calculation requires computing the director’s total income from all sources during the relevant financial year and determining whether transactions with the company and its group entities exceed this threshold.

For example, if a proposed independent director earned Rs 50 lakh total income in a year, transactions with the target company up to Rs 5 lakh would fall within the exemption. Transactions exceeding this amount—whether as consulting fees, business contracts, rental payments, or any other pecuniary dealings—would disqualify the individual. This calculation must be performed separately for each of the two preceding financial years and the current year, meaning eligibility requires compliance across all three periods.

Independent directors are expressly barred from receiving stock options, and may only be paid sitting fees, expense reimbursements, and profit-related commission under Section 197. Where a company has no or inadequate profits, an independent director may still be paid remuneration in accordance with Schedule V.

Financial restrictions on relatives (shareholding, indebtedness, guarantees, 2% turnover relationships)

Section 149(6)(d) extends financial independence requirements to the independent director’s relatives, recognizing that family members’ financial interests can indirectly compromise directorial independence. Relatives cannot hold securities or have financial interests in the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies during the two preceding financial years or current year, except within specified thresholds. The restrictions cover four distinct categories: shareholding (limited to Rs 50 lakh face value or 2% of paid-up capital, whichever is lower), indebtedness to the company or group entities exceeding Rs 50 lakh, guarantees or security provided for third-party indebtedness exceeding Rs 50 lakh, and any other pecuniary transactions amounting to 2% or more of the company’s gross turnover or total income.

The 2% turnover relationship restriction is particularly broad, capturing any commercial dealings between relatives and the company that reach material significance. For instance, if a company has Rs 100 crore annual turnover, any relative’s business transactions (as supplier, customer, service provider, or any other commercial relationship) exceeding Rs 2 crore would disqualify the director candidate. This provision must be evaluated cumulatively—if a relative has multiple types of relationships (shareholding plus business dealings plus loans), their combined value matters. Even if each relationship individually falls below thresholds, their aggregate effect under sub-clause (d)(iv) can trigger disqualification if the combined pecuniary relationship reaches 2% of gross turnover or total income.

Shareholding thresholds for relatives (₹50 lakh and 2% of paid-up capital)

Rule 5(2) of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 clarifies that relatives of an independent director may hold securities in the company only if the face value does not exceed Rs 50 lakh OR 2% of the company’s paid-up share capital, whichever is lower.

This dual threshold creates a sliding scale based on company size—in smaller companies, the 2% threshold might be more restrictive, while in large corporations, the Rs 50 lakh absolute cap applies. For example, in a company with Rs 100 crore paid-up capital, 2% would be Rs 2 crore, but the Rs 50 lakh cap would govern, limiting relatives to securities with Rs 50 lakh face value regardless of market value.

Critically, this restriction applies to face value of securities, not market value, meaning that even if shares have appreciated significantly in market value, only the face value counts toward the threshold. The restriction covers holdings in the company itself as well as its holding, subsidiary, and associate companies, requiring a comprehensive audit of all relatives’ shareholdings across the entire corporate group.

If any single relative or multiple relatives collectively exceed these thresholds in any group entity during the two preceding financial years or current year, the director candidate is disqualified. Companies must conduct thorough due diligence during the appointment to verify compliance, and directors must monitor ongoing compliance as relative holdings can change through inheritance, gifts, or market transactions.

How do employment and professional relationships affect independent director eligibility?

Employment and professional service relationships create potential conflicts of interest that can compromise independent judgment, necessitating strict cooling-off periods and restrictions under both the Companies Act and SEBI regulations. Section 149(6)(e) recognizes that individuals who previously served as employees, key managerial personnel, or professional service providers to the company may carry institutional loyalties, business dependencies, or personal relationships that interfere with objective oversight.

These provisions establish temporal and financial thresholds designed to ensure sufficient separation between past professional engagements and current independent director roles, protecting the integrity of board governance.

Cooling-off rules for former employees and KMPs

Section 149(6)(e)(i) disqualifies any person who was a key managerial personnel (KMP) or employee of the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies during any of the three financial years immediately preceding the year of proposed appointment. This three-year cooling-off period ensures that former executives, managers, and employees develop sufficient independence from their previous employer before assuming oversight responsibilities. The restriction applies regardless of the seniority of the position held—even junior employees are barred during the cooling-off period—though the practical impact is greatest for former KMPs who held significant decision-making authority and developed deep institutional relationships during their employment tenure.

Restrictions on Former Auditors, CSs, CAs, and Consulting/Law Firms (10% Firm Turnover Rule)

Section 149(6)(e)(ii) creates comprehensive restrictions on professional service providers, barring individuals who were employees, proprietors, or partners of firms that served as auditors (statutory or internal), company secretaries in practice, cost auditors, legal consultants, or consulting firms to the company or its group entities during the three immediately preceding financial years.

Additionally, the provision disqualifies anyone associated with any legal or consulting firm that had transactions with the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies amounting to 10% or more of the firm’s gross turnover during the same period. This dual restriction addresses both the nature of services provided and the materiality of the business relationship.

The 10% firm turnover threshold creates particular challenges for practicing chartered accountants, company secretaries, and lawyers who may have provided professional services to multiple clients through their firms. Consider a CA firm with Rs 5 crore annual turnover—if the firm earned Rs 50 lakh or more from the target company or its group entities in any of the preceding three years, any partner in that firm is disqualified from becoming an independent director.

This calculation requires the firm-level assessment, meaning even partners who did not personally service the company account are tainted by the firm’s business relationship. The restriction applies equally to sole proprietorships, partnerships, and LLPs, and covers audit services, tax advisory, management consulting, legal representation, secretarial compliance, or any other professional services category.

A person is also disqualified from being an independent director if they are the Chief Executive Officer or director of any non-profit organisation that either receives 25% or more of its annual receipts from the company, its promoters, directors, or group entities, or that holds 2% or more of the company’s total voting power.

Voting power limits — not holding 2% or more voting rights

Section 149(6)(e)(iii) prohibits independent directors and their relatives from together holding 2% or more of the total voting power in the company. This voting power threshold differs from the shareholding restriction under sub-clause (d)—while relatives’ shareholding is capped at Rs 50 lakh face value or 2% of paid-up capital for their holdings alone, the voting power restriction applies to the combined holdings of the director and all relatives collectively. Voting power is calculated based on voting rights attached to shares, meaning non-voting preference shares or differential voting rights shares require special calculation to determine actual voting power rather than simple shareholding percentage.

SEBI-specific restriction for relatives or the director being a material supplier, service provider, customer, lessor, or lessee

Regulation 16(1)(b)(vi) of SEBI LODR Regulations adds an additional layer of restrictions not found in the Companies Act, disqualifying independent directors who are material suppliers, service providers, customers, lessors, or lessees of the company. The regulation defines “material” as any relationship that accounts for 2% or more of the company’s turnover or expenses, or Rs 50 lakh, whichever is lower. This restriction extends to the director’s relatives, creating a comprehensive bar on commercial relationships between the director’s family network and the listed company. Unlike the Companies Act’s exclusive focus on financial and employment relationships, SEBI’s provision captures operational business relationships—meaning even if a director has no ownership stake or consulting arrangement, being a major supplier or customer disqualifies them from independent directorship in listed companies.

What legal disqualifications can prevent a person from meeting independent director eligibility?

Beyond the positive eligibility criteria and financial independence requirements, Indian corporate law establishes specific legal disqualifications that create absolute bars to independent directorship regardless of a candidate’s qualifications or experience. These disqualifications recognize that certain legal violations, regulatory sanctions, and structural conflicts are fundamentally incompatible with the fiduciary duties and ethical standards expected of independent directors. Understanding these disqualifications is critical for both aspiring directors conducting eligibility self-assessments and companies evaluating candidate suitability, as overlooking these bars can result in invalid appointments, regulatory penalties, and governance failures.

Age requirements — minimum 21 years under SEBI LODR

While the Companies Act 2013 establishes only a minimum age of 18 years for directorship generally (implied through the Indian Contract Act 1872, allowing individuals above 18 to consent to act as directors), Regulation 17(1A) of SEBI LODR Regulations imposes a higher minimum age threshold of 21 years specifically for independent directors of listed companies.

Listed companies must therefore ensure that any independent director appointment complies with the more stringent SEBI age requirement. There is no maximum age limit under the Companies Act 2013 for independent directors, allowing individuals of any advanced age to serve if they meet all other eligibility criteria and possess the requisite competence and experience to contribute meaningfully to board governance.

Section 164 disqualifications

Section 164 of the Companies Act 2013 establishes comprehensive disqualifications that apply to all directors, including aspiring independent directors, creating absolute bars based on financial irregularities, legal violations, and governance failures.

A person is disqualified from being appointed as a director if they have been convicted of any offense involving moral turpitude and sentenced to imprisonment for not less than six months (disqualification lasts five years from conviction), have not paid calls on shares held by them within six months from the due date, have been declared insolvent, or have applied to be adjudicated as an insolvent (disqualification continues until discharge). These character-based disqualifications recognize that certain financial irresponsibility and criminal conduct are incompatible with director fiduciary duties.

Section 164(2) creates disqualifications for directors of companies that have failed to file financial statements or annual returns with the Registrar of Companies for three consecutive financial years, or failed to repay deposits, redeem debentures, or pay interest/dividends where such amounts remain unpaid for one year or more.

Directors of such companies are disqualified from appointment or reappointment in any company for five years from the date of default.

This provision creates contagion effects—being a director of one non-compliant company disqualifies the individual from all other directorships during the penalty period. Companies must therefore conduct comprehensive due diligence on a candidate’s past and current directorships, verifying that none of those companies are in default, as appointment of a disqualified person renders the appointment void ab initio.

DIN suspension, past defaults, and related bars

The Director Identification Number (DIN) is mandatory for all directors, and its deactivation or cancellation is governed by Sections 153 to 159 of the Companies Act, 2013, read with Rule 11 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014, which empower the MCA to deactivate or cancel a DIN for reasons including failure to file prescribed returns, furnishing false information, or non-compliance with Rule 6 databank requirements.

A suspended or deactivated DIN creates an absolute bar to appointment as an independent director, as a valid DIN is mandatory for all directors. Individuals whose DINs have been suspended must apply for reactivation by rectifying the underlying non-compliance, paying prescribed fees, and obtaining MCA approval before becoming eligible for any directorship.

Past defaults in other companies can create ongoing eligibility issues even after penalties have been paid or suspensions lifted.

For instance, if a person was previously convicted under any provision of the Companies Act or the Securities and Exchange Board of India Act and the conviction involved moral turpitude with imprisonment of six months or more, the five-year disqualification period under Section 164(1)(a) operates automatically from the date of conviction.

Similarly, if a person was a director of a company that defaulted in deposit repayment, debenture redemption, or dividend payment, the Section 164(2) disqualification continues for five years even if the person has resigned from that company. These temporal bars require careful tracking of past events and calculation of disqualification periods to determine current eligibility.

Cross-directorship restrictions under sebi — no reciprocal relationships

Regulation 26(1) of SEBI LODR Regulations prohibits any reciprocal or cross-directorship arrangements that could compromise independence. An independent director of a listed company cannot serve as a director (independent or otherwise) in more than seven listed companies. Furthermore, if the independent director is a whole-time director in any listed entity, they can serve as an independent director in only three other listed companies. This cap ensures that directors have sufficient time and attention to devote to their oversight responsibilities and prevents the emergence of a small circle of professional directors who serve on multiple interlocking boards.

SEBI regulations also prohibit specific reciprocal arrangements where independent director A serves on Company X’s board while independent director B (from Company X) serves on Company Y’s board where director A has executive responsibilities. Such cross-directorship creates mutual accommodation risks where directors may soften their oversight of each other’s companies. Listed companies must conduct conflict checks during independent director appointments to ensure no such reciprocal relationships exist. These structural independence protections go beyond the Companies Act baseline, recognizing that concentrated directorship networks and reciprocal arrangements can undermine the independent oversight function even when directors technically meet all other eligibility criteria.

Conclusion

Independent director eligibility in India operates through a sophisticated multi-layered framework that combines the Companies Act 2013’s foundational requirements with SEBI’s supplementary conditions for listed companies. This dual regulatory structure ensures that independent directors possess not only the requisite competence and integrity but also maintain comprehensive financial, professional, and personal independence from the companies they oversee.

The framework’s complexity—spanning positive qualifications, financial thresholds, relative restrictions, employment cooling-off periods, and legal disqualifications—reflects the critical governance role independent directors play in protecting stakeholder interests and ensuring corporate accountability.

For aspiring independent directors, thorough self-assessment against all eligibility criteria is essential before pursuing databank registration or accepting board appointments. Companies must conduct comprehensive due diligence during director selection, verifying not just the candidate’s qualifications and experience but also the absence of disqualifying relationships with the company, its group entities, promoters, and existing directors.

Understanding these eligibility requirements enables both individuals and organizations to navigate the appointment process confidently while maintaining compliance with India’s evolving corporate governance standards. As regulatory expectations continue to tighten, particularly for listed companies, mastering independent director eligibility criteria becomes increasingly important for effective board composition and governance excellence.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the basic eligibility criteria to become an independent director in India?

An independent director must be a person of integrity with relevant expertise, cannot be a promoter or related to promoters/directors, must have no pecuniary relationships with the company (except minor transactions under 10% of total income), and their relatives cannot hold more than Rs 50 lakh or 2% shareholding.

Can a relative of an independent director hold shares in the company?

Yes, relatives can hold shares if the face value does not exceed Rs 50 lakh OR 2% of the company’s paid-up capital, whichever is lower, and the combined voting power of the director and all relatives does not exceed 2%.

What is the minimum and maximum age to become an independent director?

The minimum age is 21 years for independent directors of listed companies under SEBI LODR Regulations, though the Companies Act requires only 18 years for unlisted companies. There is no maximum age limit under the Companies Act 2013.

Can a practicing Chartered Accountant become an independent director?

A practicing CA can become an independent director only if they were not an auditor, tax consultant, or service provider to the company or its group entities during the preceding three financial years, and their firm’s dealings with the company did not exceed 10% of firm turnover.

What is the pecuniary relationship restriction under Section 149(6)?

Section 149(6) prohibits independent directors from having any pecuniary relationship with the company or its group entities during the two preceding financial years or current year, except for director remuneration and transactions not exceeding 10% of the director’s total income.

Can an independent director have been an employee of the company?

No, individuals who were key managerial personnel or employees of the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies during any of the three financial years immediately preceding the proposed appointment are disqualified from independent directorship.

What disqualifies a person from becoming an independent director?

Disqualifications include Section 164 bars (convictions involving moral turpitude, insolvency, defaults in filing/payments), DIN suspension, being a promoter or related to promoters/directors, failing financial independence thresholds, and holding 2% or more voting power in the company.

Is registration with IICA databank mandatory for independent director eligibility?

IICA databank registration is not mandatory for eligibility itself, but Rule 6 of the Appointment Rules requires individuals willing to be appointed as independent directors to register with the databank and pass the online proficiency self-assessment test within specified periods.

For a detailed strategy on preparing for and passing the IICA test, refer to our guide on how to clear the independent director exam.

Can a person be an independent director in multiple companies?

Yes, but SEBI LODR Regulations cap independent directors at serving in maximum seven listed companies; if serving as whole-time director in any listed company, the limit is three other listed companies as independent director.

What is the difference between Companies Act and SEBI eligibility requirements?

SEBI LODR Regulations add stricter requirements for listed companies including minimum age 21 years (vs 18 under Companies Act), restrictions on material supplier/customer relationships, cross-directorship limits, and enhanced disclosure obligations beyond the Companies Act baseline.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications