Learn how to define Independent Director under Section 149(6) of the Companies Act 2013 and SEBI LODR Regulation 16. Understand eligibility, material relationships, and key compliance requirements.

Table of Contents

When you’re navigating India’s corporate governance landscape, understanding what makes a director “independent” isn’t just about memorizing statutory language—it’s about grasping a fundamental principle that protects shareholder interests and ensures unbiased board oversight.

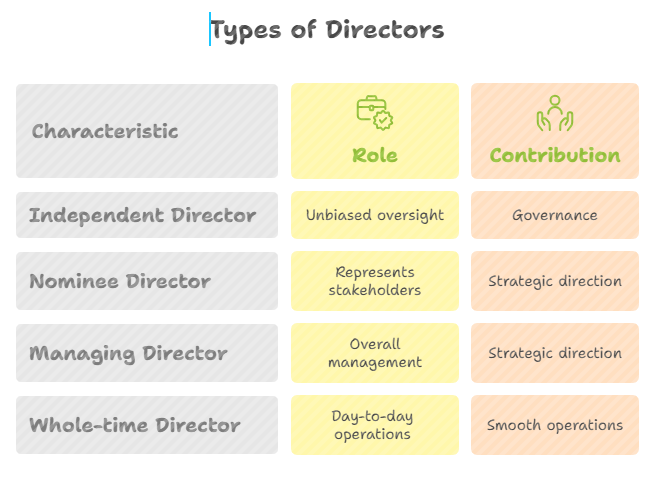

An independent director is essentially a non-executive board member who brings impartial judgment to corporate decision-making precisely because they lack the financial, familial, or professional ties that could compromise their objectivity. If you’re considering this role, learn how to become an independent director step-by-step.

Unlike executive directors who manage day-to-day operations or nominee directors who represent specific stakeholder interests, independent directors serve as watchdogs—scrutinizing management decisions, safeguarding minority shareholder rights, and ensuring the company adheres to governance best practices. The entire regulatory framework around independent directors rests on one core principle: these individuals must be genuinely free from relationships that could cloud their judgment or create conflicts of interest.

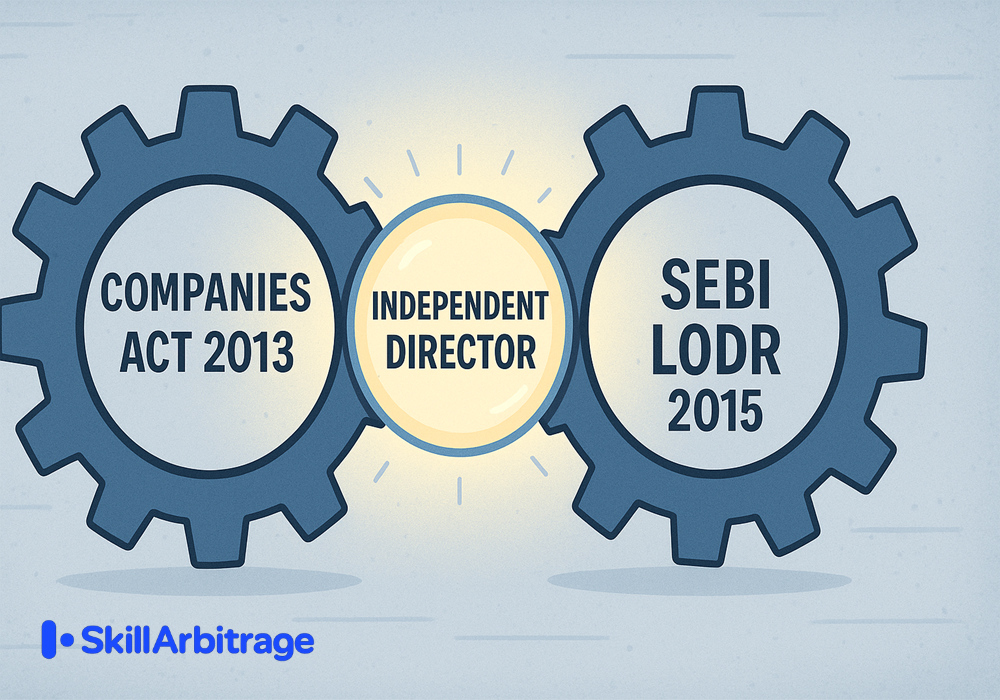

The definition of an independent director in India operates through a dual regulatory framework. For all public companies meeting certain thresholds, Section 149(6) of the Companies Act 2013 provides the foundational criteria. For listed companies specifically, SEBI’s Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements (LODR) Regulations 2015, particularly Regulation 16(1)(b), add an additional layer of requirements. Both frameworks work together to ensure that independent directors maintain true independence—not just on paper, but in practice.

I’m going to walk you through exactly how Indian law defines an independent director, starting with the conceptual foundation and then diving into the precise legal requirements under both the Companies Act 2013 and SEBI regulations.

How does one define independent director in accordance with Indian corporate laws?

In corporate governance, “independence” refers to the ability of a director to exercise judgment free from influence, bias, or conflicts of interest that might compromise their duty to act in the company’s best interest.

When we say a director is independent, we mean they have no material relationship with the company, its promoters, or its management that could affect their decision-making. This independence is what allows them to challenge management when necessary, question strategic decisions objectively, and protect the interests of all shareholders—especially minority shareholders who otherwise have little voice in board decisions.

Independence isn’t merely about being an outsider or not holding an executive position. It’s about the absence of relationships—whether financial, familial, or professional—that create dependencies or obligations. A director might not work for the company, but if their consulting firm derives 40% of its revenue from that company, can they really vote objectively on management compensation or related party transactions?

The regulatory framework recognizes that true independence requires both structural separation (not being part of management) and relational separation (not having material ties that create conflicts). This is why the legal definition goes far beyond simply requiring directors to be “non-executive.”

How does section 149(6) of the companies act 2013 define independent director?

Section 149(6) of the Companies Act 2013 defines an independent director as “a director other than a managing director or a whole-time director or a nominee director” who meets specific criteria designed to ensure their independence.

The statute begins by establishing what an independent director is NOT—they cannot be any form of executive director or a nominee representing specific interests. From there, the definition builds a comprehensive framework requiring that the person possess integrity and relevant expertise in the board’s opinion, and critically, that they have no relationships with the company, its promoters, or management that could compromise independent judgment.

The definition operates through six detailed sub-clauses covering

- promoter relationships,

- pecuniary relationships,

- restrictions on relatives,

- past employment or professional relationships,

- shareholding limits, and

- involvement with non-profit organizations connected to the company.

Each criterion addresses a different type of potential conflict.

For instance, subsection 149(6)(c) prohibits any material pecuniary relationship exceeding 10% of the director’s income during the current or preceding two financial years, while subsection (e) disqualifies anyone who has been a key managerial personnel or employee in the preceding three years.

How does Regulation 16 of the SEBI LODR 2015 define independent director?

Regulation 16(1)(b) of the SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations 2015 defines an independent director for listed companies as “a non-executive director, other than a nominee director” who satisfies the conditions specified in Section 149(6) of the Companies Act 2013, along with additional criteria specific to listed entities.

SEBI’s definition builds upon the Companies Act foundation but adds enhanced requirements recognizing that listed companies have broader stakeholder bases and greater public interest considerations. The regulation emphasizes that listed company boards need directors who can provide truly independent oversight of management and protect dispersed public shareholders.

SEBI’s framework introduced stricter thresholds through subsequent amendments, particularly the 2021 Third Amendment which extended cooling periods from two to three years and tightened financial relationship limits.

The regulation also addresses situations the Companies Act doesn’t explicitly cover—such as restrictions on being a non-independent director of another company where any non-independent director of the listed entity serves as an independent director.

This cross-directorship limitation, along with requirements around material suppliers, service providers, and customers, reflects SEBI’s holistic approach to assessing independence. You can access the complete regulatory text through SEBI’s LODR Regulation 16.

Difference in how companies act and SEBI LODR define Independent director?

The key difference lies in scope and stringency: Section 149(6) of the Companies Act 2013 applies to all public companies meeting specific thresholds, while SEBI LODR Regulation 16(1)(b) applies exclusively to listed companies and adds stricter requirements on top of the Companies Act baseline.

Think of the Companies Act as establishing the floor—the minimum criteria any independent director must meet. SEBI regulations then raise the ceiling for listed companies, recognizing that entities with publicly traded securities need enhanced governance protections. A director might meet the Companies Act definition but still fail SEBI’s additional tests.

The practical differences manifest in several ways.

SEBI’s 2021 amendments extended the cooling period for certain relationships from two to three financial years, meaning former employees, Key Managerial Personnel, or professional service providers must wait three years before becoming independent directors of listed companies, whereas unlisted companies following only the Companies Act face a shorter waiting period.

SEBI also introduced more granular restrictions on cross-directorships and enhanced thresholds for security holdings and pecuniary relationships. For example, SEBI explicitly addresses scenarios involving material suppliers and customers—relationships that could create economic dependencies even without direct financial transactions.

Furthermore, SEBI imposes procedural requirements that don’t exist under the Companies Act alone. Listed companies must pass special resolutions for appointing, reappointing, or removing independent directors, and must disclose detailed reasons for resignation along with the independent director’s letter to stock exchanges. The evaluation process is also more rigorous—SEBI mandates that boards assess not just performance but specifically whether the director continues to fulfill independence criteria. This dual-layer framework means that for listed companies, you must satisfy both sets of requirements, and where they differ, the stricter SEBI standard prevails. The regulatory guidance from SEBI, including informal guidance and enforcement orders, emphasizes that independence must be assessed holistically, not just as a checklist exercise.

How do independent directors differ from other types of directors?

Understanding the distinctions between independent directors and other director categories is crucial because these differences define the unique role independent directors play in corporate governance. The law creates clear boundaries between executive directors (who manage the company), nominee directors (who represent specific interests), and independent directors (who provide unbiased oversight). Let me clarify exactly what sets independent directors apart from these other board positions.

How are independent directors different from nominee directors?

The fundamental distinction between independent directors and nominee directors lies in who they represent and where their loyalties lie. A nominee director is appointed by a specific stakeholder—typically a lender, financial institution, investor, or government body—to represent and protect that stakeholder’s particular interests on the board. Their very purpose is to be non-independent; they’re placed on the board to ensure their appointing authority’s concerns are heard and addressed. For example, when a bank provides substantial financing, it might require the right to appoint a nominee director who monitors the company’s financial decisions from the lender’s perspective.

Independent directors, in contrast, must not represent any particular constituency’s interests. Section 149(6) explicitly states that an independent director is “a director other than a managing director or a whole-time director or a nominee director.” Their job is to represent the interests of the company as a whole, including minority shareholders who otherwise lack board representation. Where a nominee director might vote based on their appointing authority’s instructions or preferences, an independent director must exercise their own judgment objectively. This is why the law prohibits nominee directors from being classified as independent directors—the two roles are fundamentally incompatible in purpose and function.

What is the difference between independent and managing director or whole-time director?

Independent directors are categorically non-executive, meaning they cannot be involved in the day-to-day management of the company, whereas managing directors and whole-time directors are executive positions responsible for running the business operations. A managing director typically serves as the CEO, making strategic and operational decisions, leading management teams, and implementing board policies. Whole-time directors similarly hold executive responsibilities, whether as CFO, COO, or other senior management roles. Section 149(6) opens by stating an independent director must be “a director other than a managing director or a whole-time director,” establishing this as the first disqualification criterion.

The distinction goes beyond job description to encompass the fundamental relationship with the company. Managing and whole-time directors are employees receiving salaries and often holding significant equity stakes through ESOPs or other arrangements. They have material financial interests in the company’s performance beyond director’s remuneration. Independent directors, however, can only receive sitting fees (capped at Rs. 1,00,000 per meeting under the Companies Act), reimbursement of expenses, and profit-linked commission approved by shareholders. They cannot receive stock options and must not hold securities exceeding specified thresholds. This compensation structure ensures independent directors remain financially separate from management, preserving their ability to evaluate and, when necessary, challenge executive decisions without personal financial conflicts clouding their judgment.

For a complete breakdown of what independent directors actually do on company boards, see our guide on the Role of Independent Director.

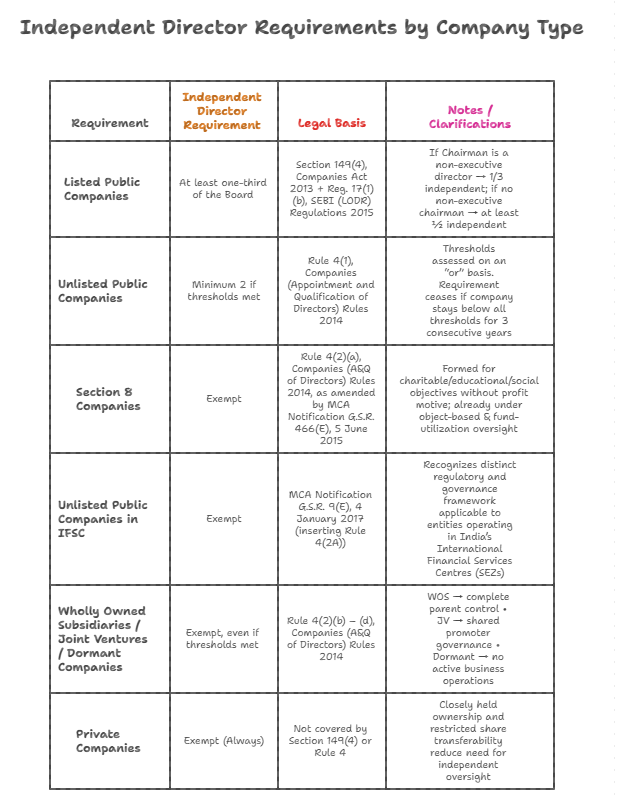

Which companies must appoint independent directors — and who is exempt?

Not every company needs independent directors, but the law casts a wide net to ensure significant companies—whether listed or unlisted—have independent board oversight. The applicability rules balance the need for governance safeguards with the practical realities of smaller companies where mandating independent directors might be burdensome. Let me break down exactly which companies must have independent directors and which ones get exemptions.

What are the requirements for listed and unlisted public companies?

One-third board composition rule for listed entities

Every listed public company must have at least one-third of its total number of directors as independent directors, as mandated by Section 149(4) of the Companies Act 2013. If calculating one-third results in a fraction, you round up to the nearest whole number—so a board with seven directors needs three independent directors (7 ÷ 3 = 2.33, rounded up to 3). This requirement applies regardless of the company’s size, revenue, or market capitalization.

SEBI LODR Regulation 17 adds nuance: if the chairman is a non-executive director, at least one-third must be independent, but if the company lacks a regular non-executive chairman, at least half the board should comprise independent directors.

Thresholds for unlisted public companies

Unlisted public companies face a different, threshold-based regime under Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014.

Your unlisted public company must appoint at least two independent directors if it meets any one of three financial thresholds:

(1) paid-up share capital of Rs. 10 crore or more,

(2) turnover of Rs. 100 crore or more, or

(3) aggregate outstanding loans, debentures, and deposits exceeding Rs. 50 crore.

These thresholds are assessed based on the figures in your latest audited financial statements, and all three criteria are evaluated on an “or” basis—meeting even one triggers the requirement.

There’s a practical relief provision: if your company ceases to meet all three conditions for three consecutive years, you’re no longer required to maintain independent directors until you again meet at least one threshold. Additionally, even if your unlisted company doesn’t meet these thresholds, you might still need a higher number of independent directors if your audit committee composition requires it, since audit committees must have specific proportions of independent directors.

Which companies are exempt from appointing independent directors?

Certain categories of companies are entirely exempt from appointing independent directors, even if they otherwise meet the financial thresholds. Section 8 companies—those established for promoting charitable, educational, religious, or social welfare objectives without profit motives—are exempted from appointing independent directors. The rationale here is that these non-profit entities already operate under strict regulatory oversight regarding their object-based restrictions and fund utilization, providing alternative governance safeguards.

Specified IFSC public companies incorporated in India’s International Financial Services Centres are also exempt, recognizing the distinct regulatory environment and governance structures applicable to entities operating in these special economic zones.

Furthermore, Rule 4 specifically exempts three types of unlisted public companies, even if they exceed the financial thresholds:

- wholly owned subsidiaries,

- joint ventures, and

- dormant companies.

The logic is straightforward—wholly owned subsidiaries are controlled entirely by their parent companies, joint ventures have built-in governance from their multiple promoters, and dormant companies by definition aren’t conducting active business operations requiring independent oversight.

One important clarification: private companies are never required to appoint independent directors under the Companies Act 2013, regardless of their size or financial metrics.

The independent director mandate applies exclusively to public companies. This reflects the fundamental difference in shareholder structure—private companies have restricted share transferability and typically closer-knit ownership, while public companies have broader, often unknown, shareholder bases requiring stronger governance protections.

How is “Independence” evaluated in practice when one define independent director?

Understanding independence isn’t just about reading statutory checklists—it’s about recognizing how these criteria function in real-world scenarios to preserve genuine objectivity.

When you’re evaluating whether someone qualifies as an independent director, you need to assess both the letter of the law and its underlying purpose: ensuring the director has no relationships that could compromise their judgment.

Let me show you how the key independence safeguards work in practice and why they matter.

What is a “material pecuniary relationship” and why does it matter?

Interpreting materiality and financial linkages

Section 149(6)(c) prohibits independent directors from having any “pecuniary relationship” with the company, its holding, subsidiary, or associate companies, or their promoters or directors, during the current or two preceding financial years, with an exception for directors’ remuneration and transactions not exceeding 10% of the director’s total income. The critical question becomes: what makes a financial relationship “material” enough to disqualify independence?

The 10% threshold provides a quantitative test, but materiality is also qualitative. If you’re a consultant earning Rs. 8 lakh annually from the company when your total income is Rs. 1 crore (8%), that’s technically within limits, but if that Rs. 8 lakh represents your only consulting contract and losing it would significantly impact your livelihood, the relationship might still be considered material.

SEBI’s enforcement approach, particularly in orders like Maxheights Infrastructure Limited (2024), emphasizes that materiality must be assessed holistically, not mechanically.

In the said order, SEBI held that appointing a director who had been an employee of the company or a promoter-group entity and had pecuniary ties meant that the independence test could not be satisfied — underscoring that independence must be assessed on a ‘facts and circumstances’ basis rather than by relying on fixed numeric thresholds.

This means you can’t rely solely on meeting the 10% test—you need to ask whether the financial relationship, regardless of percentage, creates a practical dependency that could compromise your independence.

Common scenarios and practical illustrations

Let me walk you through some common situations.

Suppose you’re a senior partner at a law firm that has provided legal services worth Rs. 75 lakh to the company over the past year, and your personal income from the firm is Rs. 10 crore. The transaction is less than 10% of your income, but Section 149(6)(e)(ii) creates a separate disqualification: you cannot have been “a partner in any of the three financial years immediately preceding” in a legal consulting firm that had transactions with the company amounting to 10% or more of the firm’s gross turnover. If Rs. 75 lakh exceeds 10% of your law firm’s turnover, you’re disqualified—even though it’s a tiny fraction of your personal income.

Here’s another scenario: your spouse owns a catering business that supplies meals to the company’s offices, generating Rs. 30 lakh in annual revenue. Section 149(6)(d)(iv) disqualifies you if your relatives have “any other pecuniary transaction or relationship with the company amounting to 2% or more of its gross turnover.”

If Rs. 30 lakh represents 3% of the company’s turnover, you cannot be an independent director, regardless of your personal involvement in the catering business.

These examples illustrate why the definition casts such a wide net—capturing not just your direct relationships but also those of your relatives and professional entities you’re associated with. The framework recognizes that conflicts of interest can arise indirectly through family members or business partners, making you beholden to interests other than pure shareholder welfare.

What restrictions safeguard independence?

Promoter and relative-based disqualifications

Section 149(6)(b) establishes two fundamental disqualifications: you cannot be or have been a promoter of the company or its group companies, and you cannot be related to any promoters or directors in the company or its group.

This prevents founders and their family members from claiming independent status, regardless of how much time has passed.

The Companies Act defines “relative” broadly under Section 2(77) to include spouse, father, mother, son, daughter, brother, and sister, along with specific in-laws and extended family members. What’s crucial here is that there’s no time limit on the promoter disqualification—if you were a promoter at any point in the company’s history, you’re permanently ineligible to become an independent director.

The relative-based restrictions extend beyond the simple family connection test. Section 149(6)(d) creates a detailed framework limiting what your relatives can do: they cannot hold securities exceeding Rs. 50 lakh face value or 2% of paid-up capital (whichever is lower), cannot be indebted to the company for more than Rs. 50 lakh, and cannot have provided guarantees exceeding Rs. 50 lakh in connection with third-party indebtedness to the company—all assessed during the current or two preceding financial years.

These limits recognize that even if you’re not personally a promoter, if your close family members have significant financial stakes or obligations involving the company, those relationships could influence your judgment. The complete relative definition and its implications are detailed in Section 2(77) of Companies Act 2013.

Financial and pecuniary relationship limitations

Beyond promoter and relative restrictions, Section 149(6) imposes strict limits on financial entanglements that could create dependencies.

You cannot have been a Key Managerial Personnel or employee of the company or its group during the three immediately preceding financial years—this cooling period ensures former executives gain sufficient distance before serving as independent directors. Similarly, you cannot hold more than 2% of the total voting power of the company either personally or together with relatives, preventing you from being a significant shareholder whose economic interests might diverge from minority shareholders.

There’s also a specific restriction regarding non-profit organizations: you cannot be a Chief Executive or director of any NPO that receives 25% or more of its receipts from the company, its promoters, or directors, or that holds 2% or more of the company’s voting power.

This addresses scenarios where charitable organizations create indirect economic dependencies—if you run a foundation heavily funded by the company, can you really challenge the CEO objectively when that relationship provides substantial resources for your philanthropic work?

The pecuniary relationship threshold (10% of your total income) applies not just to direct compensation but to any financial dealings, whether as consultant, vendor, service provider, or in any other capacity. SEBI’s LODR Regulation 16(1)(b) adds further restrictions for listed companies.

How has the independent director definition evolved?

The journey from vague aspirations to precise statutory requirements tells you a lot about how corporate governance reforms have responded to business scandals, investor demands, and international best practices. India’s approach to defining independent directors has evolved dramatically over the past two decades, moving from almost complete silence in the 1956 Act to exhaustive criteria in current law. Understanding this evolution helps you appreciate why the definition is structured the way it is today.

From Companies Act 1956 to 2013

The Companies Act 1956 contained no specific definition of “independent director” at all—the term simply didn’t exist in statutory vocabulary.

The 1956 Act recognized directors generally and had provisions for managing directors, whole-time directors, and directors in general categories, but it didn’t create a distinct category for independent oversight. Corporate boards operated largely without statutory requirements for independent members, though some progressive companies voluntarily appointed independent directors following international trends. This absence of definition meant that when companies did appoint “independent” directors, the term had no legal meaning or enforceable criteria—independence was whatever the company decided it meant.

The shift began with regulatory push rather than legislative amendment. SEBI, concerned about corporate governance failures and the need to protect minority investors in listed companies, introduced Clause 49 to listing agreements in the early 2000s, which I’ll discuss in the next section. When the Companies Act 2013 was drafted, the concept of independent directors was finally given full statutory recognition. Section 149 established the requirement framework while Section 149(6) provided the detailed definition we work with today. The 2013 Act represented a paradigm shift—from voluntary best practice to mandatory requirement, from undefined concept to exhaustive criteria.

The transformation wasn’t merely about adding a definition; it reflected fundamental changes in India’s corporate governance philosophy. The 2013 Act recognized that minority shareholders needed champions on the board who weren’t beholden to promoters or management. Schedule IV of the Act, which prescribes the code of conduct for independent directors, further institutionalized their role by spelling out duties, guidelines for professional conduct, and evaluation mechanisms. This statutory framework created an enforceable regime where independence could be objectively assessed, violations could be penalized, and shareholders could demand genuine independent oversight.

Clause 49 to SEBI LODR transition

Before the SEBI LODR Regulations came into effect in 2015, listed companies were governed by Clause 49 of the listing agreement—a contractual provision between the stock exchange and listed companies that defined corporate governance requirements. Clause 49, introduced in its comprehensive form around 2004 following the Narayana Murthy Committee recommendations, was India’s first serious attempt to define and mandate independent directors for listed companies. It defined independent directors as those who “apart from receiving director’s remuneration, do not have any other material pecuniary relationship or transactions with the company” that could affect independence of judgment in the board’s opinion.

While Clause 49 was groundbreaking, it had limitations. As a contractual provision, its enforcement relied on stock exchange actions rather than direct regulatory authority. The definition was less precise than what we have today—focusing primarily on pecuniary relationships without the detailed disqualifications regarding promoters, relatives, and past employment that Section 149(6) now contains. Furthermore, being part of a listing agreement rather than regulations meant it lacked the force and visibility of standalone regulatory provisions. Companies sometimes treated Clause 49 as mere compliance paperwork rather than substantive governance reform.

The transition to SEBI LODR Regulations 2015 represented a consolidation and enhancement of Clause 49’s governance requirements. SEBI merged various listing agreement provisions into a unified regulatory framework, and Regulation 16(1)(b) on independent directors built upon both Clause 49’s legacy and the Companies Act 2013’s statutory foundation. The LODR framework made enforcement more direct—violations are now regulatory breaches subject to SEBI’s enforcement powers, not just contractual defaults. Subsequent amendments, particularly the 2021 Third Amendment, further tightened independence criteria by extending cooling periods, enhancing pecuniary relationship thresholds, and introducing restrictions on cross-directorships. You can trace this evolution through SEBI’s LODR Regulations and its amendment history.

Conclusion

Defining an independent director in Indian corporate law is far more nuanced than simply identifying someone who doesn’t work for the company. As you’ve seen throughout this guide, true independence requires careful assessment of financial relationships, family connections, past employment, shareholdings, and even involvement with related non-profit organizations.

The dual regulatory framework—Section 149(6) of the Companies Act 2013 for all public companies and SEBI LODR Regulation 16(1)(b) for listed entities—creates a comprehensive web of criteria designed to ensure directors can exercise judgment free from conflicts of interest or undue influence.

What matters most when you define independent director is understanding that the law looks beyond surface-level separation to examine substantive relationships that could compromise objectivity.

Whether you’re a company appointing independent directors, a professional considering such a role, or a shareholder evaluating board composition, you need to assess independence holistically—asking not just whether someone meets the checklist criteria, but whether they’re genuinely positioned to challenge management, protect minority interests, and provide unbiased governance oversight. That’s the true measure of independence that all these regulatory provisions ultimately seek to achieve.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who cannot be appointed as an independent director?

You cannot be appointed as an independent director if you are a managing director, whole-time director, or nominee director, or if you’ve been a promoter or are related to promoters or directors. Past employees, Key Managerial Personnel, or partners in audit/legal/consulting firms that served the company within the preceding three years are also disqualified.

Can an independent director hold shares in the company?

Yes, but with strict limits. An independent director and their relatives together cannot hold securities exceeding Rs. 50 lakh face value or 2% of the company’s paid-up capital, whichever is lower, as per Section 149(6)(d)(i).

What is the maximum sitting fee for independent directors?

The maximum sitting fee for independent directors is Rs. 1,00,000 per meeting under Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Remuneration of Managerial Personnel) Rules 2014. However, the sitting fee paid to independent directors and women directors cannot be less than that paid to other directors.

Can a company secretary be appointed as an independent director?

A practicing company secretary can be appointed as an independent director in any company. However, a company secretary employed as a whole-time employee in one company cannot serve as an independent director in the same company since independent directors cannot be employees, though they can serve as independent directors in other companies.

What is the minimum age requirement for independent directors?

Under the Companies Act 2013, the minimum age to be appointed as an independent director is 18 years with no maximum age limit. However, for listed companies under SEBI LODR Regulations 2015, the minimum age is 21 years and the maximum age is 70 years.

How long can an independent director serve on a board?

An independent director can serve for a maximum term of five consecutive years per appointment. They can be reappointed for a second consecutive five-year term by passing a special resolution. However, after two consecutive terms (10 years total), they must wait three years before becoming eligible for reappointment as an independent director.

Can relatives of an independent director have financial dealings with the company?

Yes, but with significant restrictions. Relatives cannot be indebted to the company for more than Rs. 50 lakh, cannot provide guarantees exceeding Rs. 50 lakh for third-party debts, and cannot have pecuniary transactions amounting to 2% or more of the company’s gross turnover, all assessed during the current and two preceding financial years.

What is the difference between independent director and outside director?

“Independent director” and “outside director” are often used interchangeably to mean a non-executive board member. However, in Indian corporate law, “independent director” has a precise statutory definition under Section 149(6) with specific eligibility criteria, while “outside director” is a more informal term simply referring to any director who isn’t part of the company’s management.

Do independent directors retire by rotation?

No, independent directors do not retire by rotation. Section 149(13) explicitly states that the provisions of Sections 152(6) and 152(7) regarding retirement by rotation do not apply to independent directors. They serve for fixed terms as specified in their appointment letters without being subject to rotational retirement requirements.

Can an independent director be appointed in more than one company?

Yes, but with limits. Under Regulation 17A of SEBI LODR 2015, an independent director can serve in a maximum of seven listed companies simultaneously. If the person is a whole-time director in any listed company, they can serve as an independent director in only three listed companies.

What happens if an independent director loses independence during tenure?

If an independent director ceases to meet the independence criteria during their tenure, they must immediately inform the board as per Schedule IV of the Companies Act 2013. Once independence is lost, they cannot continue as an independent director and their position becomes vacant, requiring the company to appoint a replacement.

Is databank registration mandatory for all independent directors?

Yes, under Rule 6 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules 2014, persons who intend to be appointed as independent directors must apply to the Indian Institute of Corporate Affairs for inclusion in the independent directors databank and pass an online proficiency self-assessment test within one year, unless exempted. For those appearing for the assessment, here’s a practical guide on how to prepare for the independent director exam.

Can an independent director receive remuneration other than sitting fees?

Independent directors can receive sitting fees, reimbursement of expenses for attending meetings, and profit-linked commission approved by shareholders in accordance with Section 197. However, they are not entitled to stock options. Any other remuneration beyond these specified categories would violate the independence criteria under Section 149(6).

What is Schedule IV of Companies Act 2013 for independent directors?

Schedule IV of the Companies Act 2013 prescribes the code for independent directors, covering their role, duties, manner of appointment, re-appointment, resignation, removal, and guidelines for professional conduct. It establishes that independent directors should uphold ethical standards, act objectively, devote sufficient time, and ensure they safeguard the interests of all stakeholders, particularly minority shareholders.

How do SEBI requirements differ from Companies Act requirements for independent directors?

SEBI LODR Regulation 16(1)(b) applies only to listed companies and adds stricter requirements beyond Section 149(6) of the Companies Act. SEBI extends cooling periods from two to three years for certain relationships, imposes additional restrictions on cross-directorships, requires special resolutions for appointment/removal, and mandates enhanced disclosures. Where requirements differ, listed companies must comply with the stricter SEBI standard.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications