Learn the complete definition of an independent director under Section 149(6) Companies Act 2013 and SEBI LODR regulations. Understand eligibility criteria, disqualifications, and IICA databank requirements with practical examples.

Table of Contents

When companies talk about appointing independent directors, there’s often confusion about who actually qualifies for this critical role.

I’ve seen countless professionals assume they meet the independence criteria, only to discover hidden disqualifications buried in regulatory fine print.

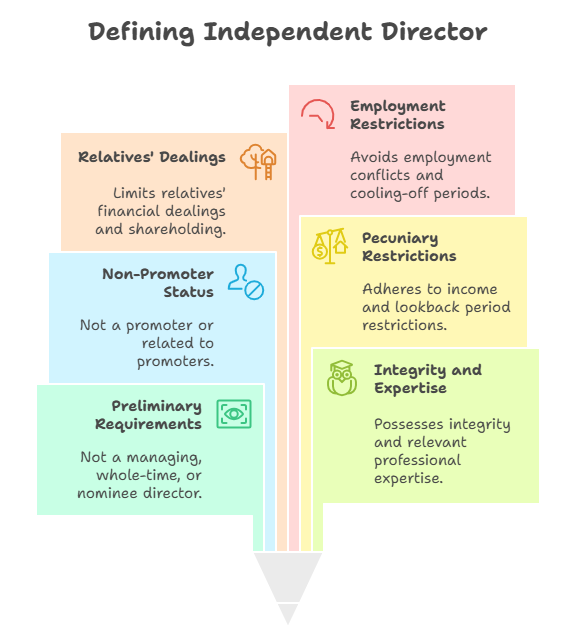

The definition of “an independent director is one who” involves navigating two overlapping regulatory frameworks—the Companies Act 2013 and SEBI LODR Regulations—each with its own set of restrictions.

Here’s what makes this particularly challenging: independence isn’t just about not being an employee. It’s a comprehensive status that examines your relationships, your relatives’ financial dealings, your professional history, and even your involvement with non-profit organizations connected to the company. One seemingly minor connection can disqualify you entirely, regardless of how qualified or ethical you are.

In this guide, I’ll walk you through the complete regulatory framework that defines independent director status in India. You’ll learn the exact criteria from Section 149(6) of the Companies Act 2013, understand how SEBI adds additional layers for listed companies, and see practical examples of situations that disqualify candidates.

By the end, you’ll know precisely whether you—or someone you’re considering appointing—truly qualifies as an independent director.

What is an independent director: an independent director is one who maintains objectivity and impartiality

Core definition under companies act 2013

An independent director is fundamentally a board member who maintains complete impartiality in their judgment. According to Section 149(6) of the Companies Act 2013, an independent director is one who is neither a managing director, whole-time director, nor a nominee director, and who maintains no material relationship with the company that could compromise their independent judgment.

The core principle is straightforward, these directors must be free from any relationships—financial, familial, or professional—that could influence their decisions in favor of management or controlling shareholders.

They are not involved in day-to-day operations, don’t hold executive positions, and maintain an arm’s-length relationship with the company beyond their directorship role.

What sets independent directors apart is their lack of skin in the game beyond their fiduciary responsibility. They don’t represent specific shareholder interests, aren’t appointed to protect particular stakeholder groups, and have no financial dependencies on the company except for legitimate director’s remuneration. This positioning allows them to provide unbiased oversight, challenge management decisions when necessary, and protect minority shareholder interests without conflicting loyalties.

Additional SEBI LODR requirements for listed companies

For listed companies, the definition becomes more stringent.

SEBI LODR Regulation 16(1)(b) adds several restrictions beyond what the Companies Act requires. This creates a dual-layer framework where listed company independent directors must satisfy both the Companies Act criteria and additional SEBI requirements simultaneously.

SEBI specifically disqualifies individuals who are non-independent directors of another company where any non-independent director of the listed entity serves as an independent director. This prevents cross-directorship arrangements that could create mutual obligation networks. Furthermore, SEBI prohibits material business relationships—you cannot be a significant supplier, service provider, customer, lessor, or lessee of the listed company or its subsidiaries and still claim independence.

The regulatory logic here is clear.

Listed companies have broader public investor bases and higher governance expectations. SEBI recognizes that relationships considered acceptable for unlisted companies could create subtle influence channels in listed companies where market confidence depends on truly independent oversight. If you’re evaluating independence for a listed company role, you must clear both the Companies Act hurdles and these additional SEBI restrictions.

Why independence matters in corporate governance

Independence is the foundation of effective board oversight.

When boards lack truly independent directors, you see the patterns that led to corporate scandals like Satyam and IL&FS in India.

Management teams face no meaningful challenges to their decisions, minority shareholders have no protection against controlling shareholder interests, and boards become rubber-stamp mechanisms rather than governance bodies.

Independent directors serve as the board’s conscience.

They ask uncomfortable questions about related party transactions, scrutinize executive compensation proposals, and ensure financial reporting reflects reality rather than management’s preferred narrative.

In conflict situations—such as promoter buyback offers or management buyouts—independent directors evaluate whether the terms are fair to all shareholders, not just insiders.

The practical impact is substantial.

Research shows companies with genuinely independent boards experience better financial performance, lower instances of fraud, and higher investor confidence.

Furthermore, independent directors bring diverse perspectives from their own professional experiences, helping companies avoid groupthink and make more balanced strategic decisions. This is why both the Companies Act and SEBI invest so heavily in defining and enforcing independence criteria—the entire corporate governance system depends on having board members who can objectively evaluate management and protect stakeholder interests.

To understand how independence translates into boardroom action, see our detailed breakdown of the roles and responsibilities of an independent director.

Section 149(6) — an independent director is one who meets legal eligibility conditions

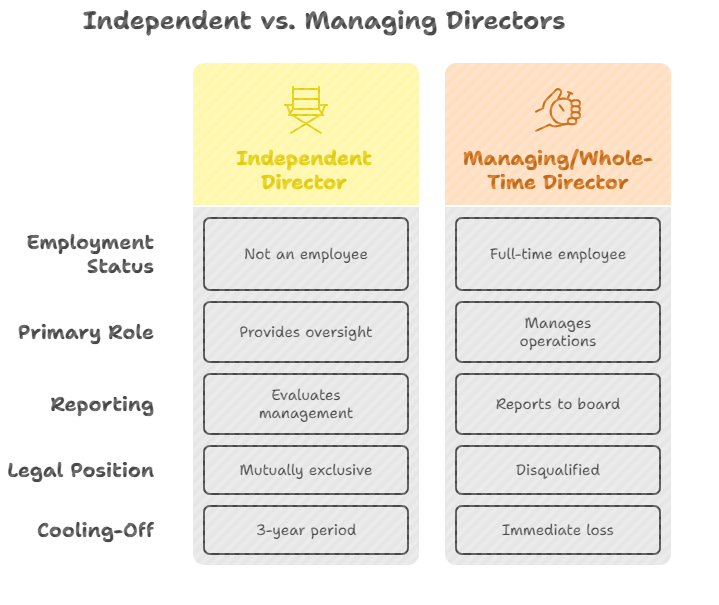

The starting point of independence under Section 149(6) of the Companies Act 2013 is definitional exclusion. You cannot be an independent director if you’re simultaneously a managing director, whole-time director, or nominee director of the company. This isn’t just about job titles—it’s about the fundamental incompatibility between executive responsibility and independent oversight.

Preliminary requirements – not a managing, whole-time, or nominee director

A managing director or whole-time director is employed by the company, receives regular salary, and is responsible for daily operations and implementation of board decisions. They report to the board and are evaluated by it. You cannot simultaneously be part of management and provide independent oversight of that same management—the conflict of interest is inherent and insurmountable.

Nominee directors represent specific stakeholder interests—typically lenders, financial institutions, or government bodies that have appointed them to protect particular interests. While nominee directors serve important functions, they’re by definition not independent because they have a mandate to represent the interests of those who nominated them. True independence requires freedom from any such mandated representation, allowing directors to evaluate issues purely on merit and company-wide stakeholder interests.

Integrity and expertise requirements

Beyond structural exclusions, Section 149(6)(a) requires that the board must affirmatively determine the proposed independent director is a person of integrity and possesses relevant expertise and experience. This is a subjective assessment, but it’s not optional or perfunctory—the board must actively satisfy itself on these points before appointment.

Integrity encompasses ethical character, professional reputation, and track record of honest dealings. The board should examine whether the candidate has faced any disciplinary actions, regulatory proceedings, or situations where their professional conduct was questioned. While past mistakes don’t automatically disqualify someone, the board needs confidence that the individual will act with probity and uphold ethical standards in their directorship role.

Relevant expertise and experience means the person brings meaningful knowledge to board deliberations. This could be expertise in finance, law, management, technology, marketing, operations, or other disciplines related to the company’s business. The requirement recognizes that independent directors add value not just through independence but through substantive contributions based on their professional background. A genuinely qualified independent director combines both independence and expertise—they’re free from conflicts while bringing knowledge that enhances board decision-making.

Non-promoter status requirement

Section 149(6)(b) creates an absolute prohibition: you cannot be or have been a promoter of the company, its holding company, subsidiary, or associate company at any time. This extends to relatives of promoters and directors as well—if you’re related to any promoter or director in the company group, you’re disqualified from independent director status.

The rationale is fundamental: promoters are the company’s founders and controlling shareholders. They have inherent influence over company direction, benefit most from company success, and often maintain informal control mechanisms beyond their formal shareholding. Someone who is or was a promoter cannot credibly claim to provide independent oversight of a company they created or controlled, regardless of how much time has passed.

The relative restriction prevents circumvention through family appointments. If the law permitted promoters’ relatives to serve as independent directors, you’d see fathers appointing sons, husbands appointing wives, and siblings appointing each other across company groups—creating the appearance of independence without its substance. The Companies Act defines “relative” broadly under Section 2(77) to include spouses, parents, children, siblings, and extended family connections, ensuring this prohibition has real teeth.

Pecuniary relationship restrictions

Section 149(6)(c) addresses the most nuanced independence criterion: pecuniary relationships. The basic rule states that an independent director should not have or have had any pecuniary relationship with the company, its holding company, subsidiary, or associate company, or their promoters or directors, during the two immediately preceding financial years or the current financial year.

However, the law recognizes that some financial transactions are inherent to the directorship role. The section explicitly exempts two categories from the pecuniary relationship prohibition: remuneration received as a director, and transactions not exceeding 10% of the director’s total income. This creates space for legitimate director fees and minor incidental transactions without compromising independence status.

What constitutes a disqualifying pecuniary relationship? Any financial dealing where you or your firm receives payments from the company beyond these exempted categories. If you’re a consultant receiving fees, a vendor supplying goods, a landlord leasing property to the company, or a professional service provider billing the company for work, these relationships create financial dependencies that compromise your ability to objectively evaluate management decisions. The two-year lookback period ensures you don’t appoint someone as an independent director immediately after ending a consulting relationship—there must be adequate cooling-off time to eliminate financial influence.

The 10% income threshold explained

The 10% income threshold serves as a materiality test for pecuniary relationships. Small, incidental transactions that represent a minor portion of your overall income don’t create meaningful financial dependency. But once company-related income crosses 10% of your total annual income, the relationship becomes material enough to potentially influence your judgment.

Here’s how this works practically: suppose you earn ₹50 lakh annually from your various professional activities. Transactions with the company worth up to ₹5 lakh (10% of ₹50 lakh) would be permissible without disqualifying your independence. However, if you provide consulting services worth ₹8 lakh to the company, you’ve crossed the threshold and no longer qualify as independent.

The 10% calculation excludes director’s remuneration—that’s separately exempted. So if you receive ₹3 lakh as director’s fees and ₹4 lakh for other transactions, only the ₹4 lakh counts toward the 10% threshold. This distinction recognizes that director compensation is a necessary component of the role itself, while other income represents additional financial ties that could create dependencies. The key principle: once company-related income becomes a significant portion of your overall earnings, you have a financial interest in maintaining good relations with management, which undermines the independence necessary for objective oversight.

Two-year lookback period

The two-year lookback period is crucial for understanding when someone becomes eligible for independent director status after having disqualifying relationships. If you had a pecuniary relationship with the company that exceeded the 10% threshold, you cannot be appointed as an independent director until two full financial years have passed since that relationship ended.

This cooling-off period serves multiple purposes. First, it ensures financial dependencies have truly dissipated—if you stopped receiving payments from the company only six months ago, those financial ties may still influence your judgment. Two years provides sufficient time for any residual sense of obligation or financial benefit to fade. Second, it prevents companies from gaming the system by temporarily pausing relationships just long enough to appoint someone as an independent director.

The lookback applies to the “two immediately preceding financial years or during the current financial year.” This means if you’re being considered for appointment in FY 2025–26, the scrutiny covers the two immediately preceding financial years—FY 2023–24 and FY 2024–25—as well as the current FY 2025–26. Any disqualifying pecuniary relationship during the current plus the two preceding years window makes you ineligible. Furthermore, this isn’t a one-time check—you must maintain independence throughout your tenure. If you develop a disqualifying pecuniary relationship after appointment, you must immediately disclose this to the board and your independent director status is compromised.

Restrictions on relatives’ financial dealings

Independence requirements extend beyond your personal financial relationships to include your relatives’ dealings with the company. Section 149(6)(d) recognizes that financial dependencies can operate indirectly through family members—if your spouse or children have significant financial ties to the company, these could influence your judgment just as effectively as direct relationships.

The restrictions on relatives’ financial dealings are comprehensive. Your relatives cannot hold securities or interests in the company exceeding specified limits, cannot be indebted to the company beyond prescribed thresholds, cannot provide guarantees for third parties’ debts to the company, and cannot have other pecuniary transactions with the company exceeding 2% of its gross turnover or total income. These provisions prevent circumventing independence requirements through family member arrangements.

What’s particularly important here is understanding that you’re responsible for knowing and disclosing your relatives’ financial relationships with the company. Before accepting an independent director position, you need to verify that your family members’ shareholdings, debts, guarantees, and business transactions all fall within permissible limits. This due diligence obligation continues throughout your tenure—if circumstances change and a relative develops a disqualifying relationship, this affects your independence status.

Shareholding limits for relatives

Section 149(6)(d)(i) with its proviso establishes clear limits on relatives’ shareholdings. Your relatives cannot hold securities or interests in the company, its holding company, subsidiary, or associate company beyond specified thresholds. The permissible limit is securities with a face value not exceeding ₹50 lakh or 2% of the paid-up capital of the company, whichever is lower.

Let’s break down what this means practically. Suppose the company has a paid-up capital of ₹100 crore. The 2% threshold would be ₹2 crore, but since the ₹50 lakh cap is lower, that becomes the operative limit. Your relatives cannot collectively hold shares with a face value exceeding ₹50 lakh. However, if the company has a paid-up capital of only ₹20 crore, the 2% threshold (₹40 lakh) is lower than ₹50 lakh, so ₹40 lakh becomes the applicable limit.

Note that this is based on face value, not market value. If your relative holds 10,000 shares with a face value of ₹10 each (total face value ₹1 lakh) that trade at ₹500 per share (market value ₹50 lakh), only the face value of ₹1 lakh counts toward the limit. This is a critical distinction—a small shareholding by face value might represent significant market value, but the independence test uses face value to avoid market fluctuation impacts. The “lower of” formula ensures that neither very small companies nor very large ones can circumvent independence requirements through shareholding structures.

Indebtedness and guarantee restrictions

Beyond shareholdings, Rule 5 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 prescribes ₹50 lakh thresholds for relatives’ indebtedness and guarantees. Your relatives cannot be indebted to the company, its holding company, subsidiary, or associate company or their promoters or directors for amounts exceeding ₹50 lakh at any time during the two immediately preceding financial years or the current financial year.

This covers both direct loans and indirect indebtedness. If your spouse borrowed ₹60 lakh from the company to purchase property, this disqualifies you from independent director status. Similarly, if your child took a loan from the company’s subsidiary that remains outstanding, you need to verify it’s below the ₹50 lakh threshold. The two-year lookback means even if the debt was repaid before your appointment, if it existed during the lookback period, it’s disqualifying.

The guarantee restriction is equally important. Your relatives cannot have given guarantees or provided security in connection with any third party’s indebtedness to the company group exceeding ₹50 lakh during the relevant period. This prevents indirect financial ties where your relative guarantees someone else’s borrowing from the company. Even though your relative isn’t directly indebted, their guarantee obligation creates a financial connection that could influence your judgment. If the company ever needs to invoke the guarantee, it would directly impact your family’s finances—creating exactly the kind of financial dependency that undermines independence.

Employment and professional service restrictions

Section 149(6)(e) creates comprehensive restrictions on employment and professional service relationships. Neither you nor your relatives can have been employees or key managerial personnel of the company or its group companies, or been associated as auditors, company secretaries, cost auditors, legal consultants, or consulting firm partners serving the company, within specified timeframes. These restrictions prevent recent employment or professional service relationships from compromising independence.

The employment restriction focuses on insider knowledge and organizational loyalty that develops through employment. If you worked for the company until recently, you likely maintain relationships with current management, may have participated in decisions you’d now be asked to oversee, and could have ongoing loyalties or grudges that color your judgment. The law recognizes that truly independent oversight requires distance from these internal dynamics.

Professional service restrictions address a different concern: financial dependency through professional engagements. Audit firms, legal consultants, and company secretaries often develop multi-year relationships with corporate clients. If you or your firm provided such services recently, appointing you as an independent director creates a potential conflict—you might be less willing to challenge management or question financial reporting if you previously certified those financials or advised on those transactions. The cooling-off periods ensure adequate time passes to eliminate these conflicts.

Key managerial personnel cooling-off period

For key managerial personnel and employees, Section 149(6)(e)(i) establishes a three-year cooling-off period. If you or any of your relatives held a position as a key managerial personnel (CEO, CFO, or company secretary) or were employees of the company, its holding company, subsidiary, or associate company in any of the three financial years immediately preceding the year of proposed appointment, you’re disqualified from independent director status.

This three-year period is longer than the two-year lookback for pecuniary relationships, reflecting the deeper influence that employment relationships create. Someone who was CFO two years ago still has extensive knowledge of company operations, likely maintains relationships with current executives, and may have participated in strategic decisions now being evaluated. Three years provides better separation from these internal connections.

There’s an important carve-out: the restriction doesn’t apply to relatives who were employees (not KMPs) during the preceding three years. This recognizes that having a cousin or nephew working in a junior position shouldn’t automatically disqualify you from independent director status. However, if your relative was a key managerial personnel, the restriction fully applies—you cannot serve as an independent director if your spouse was the company’s CFO just two years ago, regardless of whether they’ve since left that position.

Restrictions on auditors and consultants

Section 149(6)(e)(ii) extends cooling-off requirements to professional service providers. You’re disqualified if you or your relatives were, in any of the three financial years immediately preceding the year of proposed appointment, employees, proprietors, or partners in firms of auditors, company secretaries in practice, cost auditors, legal consultants, or consulting firms that served the company or its group.

Two categories exist here with different thresholds. For audit firms, company secretary firms, and cost auditor firms, any service relationship during the three-year period is disqualifying—there’s no materiality threshold. The law treats audit relationships as inherently significant because these professionals certify financial statements and compliance. You cannot serve as an independent director of a company whose books you audited just two years ago.

For legal and consulting firms, the restriction applies only if the firm had transactions with the company or its group amounting to 10% or more of the firm’s gross turnover. This materiality test recognizes that large law firms and consulting firms may have incidental dealings with hundreds of companies. A brief, minor engagement doesn’t create the same dependency as audit relationships. However, once the company becomes a significant client representing 10% or more of your firm’s revenue, that financial dependency disqualifies you from independent director status even after you’ve left the firm—provided the relationship existed within the three-year lookback period.

Shareholding and voting power limits

Beyond the restrictions on relatives’ shareholdings, Section 149(6)(e)(iii) imposes direct limits on your own shareholding. You cannot hold shares of the company. This is a bright-line rule—once your combined shareholding crosses 2% of voting rights, you’re no longer independent regardless of all other factors.

The 2% threshold is based on voting power, not equity ownership. In companies with different share classes carrying different voting rights, you need to calculate based on actual votes controlled. If you hold 1.5% of equity shares with full voting rights and your spouse holds 0.6%, your combined 2.1% voting power disqualifies you. The calculation includes all relatives as defined under the Companies Act.

This restriction recognizes that significant shareholders have financial interests that could conflict with independent oversight. If you control 3% of votes, you have meaningful influence over shareholder resolutions, stand to gain financially from decisions that increase share value, and might prioritize shareholder returns over other stakeholder interests. True independence requires that you not have skin in the game beyond your director’s remuneration—your judgment should be based purely on what’s right for the company as a whole, not on optimizing your personal investment returns.

Restrictions related to non-profit organizations

Section 149(6)(e)(iv) addresses an often-overlooked independence concern: relationships through non-profit organizations. You cannot be a Chief Executive or director of any non-profit organization that receives 25% or more of its receipts from the company, its promoters, directors, or group companies, or that holds 2% or more of the total voting power in the company.

This provision closes a potential loophole. Without it, companies could funnel charitable contributions to non-profits run by potential independent directors, creating financial dependencies that compromise independence while maintaining the appearance of propriety. If the charity you run receives a quarter or more of its funding from the company, your objectivity in evaluating that company’s performance is reasonably questionable—you have a financial interest in maintaining good relations to ensure continued charitable funding.

The 2% voting power test addresses reverse situations where the non-profit itself is a significant shareholder. If you’re a director of a foundation that owns 3% of the company’s shares, you represent that foundation’s interests as a major shareholder. This is fundamentally incompatible with serving as an independent director who’s supposed to balance all stakeholder interests. The restriction ensures that directors with obligations to significant institutional shareholders cannot simultaneously claim independent status.

What additional criteria does SEBI LODR regulation 16(1)(b) impose?

Cross-directorship restrictions

SEBI LODR Regulation 16(1)(b)(viii) introduces a restriction that doesn’t exist in the Companies Act: prohibition on cross-directorship arrangements. You cannot be an independent director of a listed company if you’re a non-independent director of another company where any of the listed company’s non-independent directors serve as independent directors.

Let me illustrate why this matters. Suppose you’re a non-independent director (say, an executive director) of Company A. Company A’s CEO serves as an independent director on the board of listed Company B. Under SEBI regulations, you cannot then serve as an independent director of Company B. The concern is mutual obligation—there’s a risk that the two directors might go easy on each other’s companies out of collegial loyalty or implicit reciprocity.

This provision prevents “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours” arrangements that could undermine independent oversight. While Companies Act restrictions focus on direct financial and employment relationships, SEBI recognizes that more subtle influence networks can operate through professional courtesies and mutual board appointments. For listed companies with broader public investor bases, SEBI demands a higher standard of independence that eliminates even these indirect relationship channels.

Material supplier and customer restrictions

SEBI LODR Regulation 16(1)(b) also prohibits independent directors from being material business partners of the listed company. You cannot be a material supplier, service provider, or customer of the company or its subsidiaries, or be a lessor or lessee in material arrangements with the company. Additionally, these restrictions extend to your relatives—if your spouse runs a company that’s a major supplier to the listed company, you cannot serve as its independent director.

The term “material” here isn’t precisely quantified in monetary terms, but SEBI expects companies to apply reasonable judgment. A relationship is material if its existence or continuation could influence the director’s independent judgment. If your business receives 30% of its revenue from supplying components to the listed company, that’s clearly material. If you sold them office supplies worth ₹50,000 once three years ago, that’s likely not material.

This restriction addresses conflicts of interest that the Companies Act’s pecuniary relationship provisions might not fully cover. Someone who owns a major supply business serving the company has a vested interest in maintaining that business relationship, which could make them reluctant to challenge management decisions or scrutinize supplier agreements. SEBI recognizes that for listed companies, even these business-to-business relationships can compromise the independence necessary for protecting public investor interests.

How SEBI requirements layer on companies act criteria

Understanding the relationship between Companies Act and SEBI LODR requirements is crucial. They don’t operate independently—for listed companies, you must satisfy both sets of criteria simultaneously. The Companies Act provides the baseline independence standards applicable to all companies (listed and unlisted), while SEBI LODR adds supplementary restrictions specifically for listed entities.

Think of it as a two-stage filter. First, you must pass all Section 149(6) criteria under the Companies Act. If you fail any of those tests—say, you were a KMP two years ago—you’re disqualified regardless of SEBI requirements. But passing the Companies Act tests isn’t sufficient for listed companies. You then face SEBI’s additional scrutiny on cross-directorships, material business relationships, and other listed company-specific concerns.

This layered structure means listed companies face stricter independence requirements than unlisted companies. Someone who qualifies as independent for an unlisted public company might not qualify for a listed company in the same group. When evaluating independence for listed company appointments, you need to work through both checklists systematically—Companies Act first, then SEBI LODR. Only candidates who clear both sets of hurdles truly qualify as independent directors for listed companies.

An independent director is one who stands apart from other director categories

Independent director vs Non-executive director

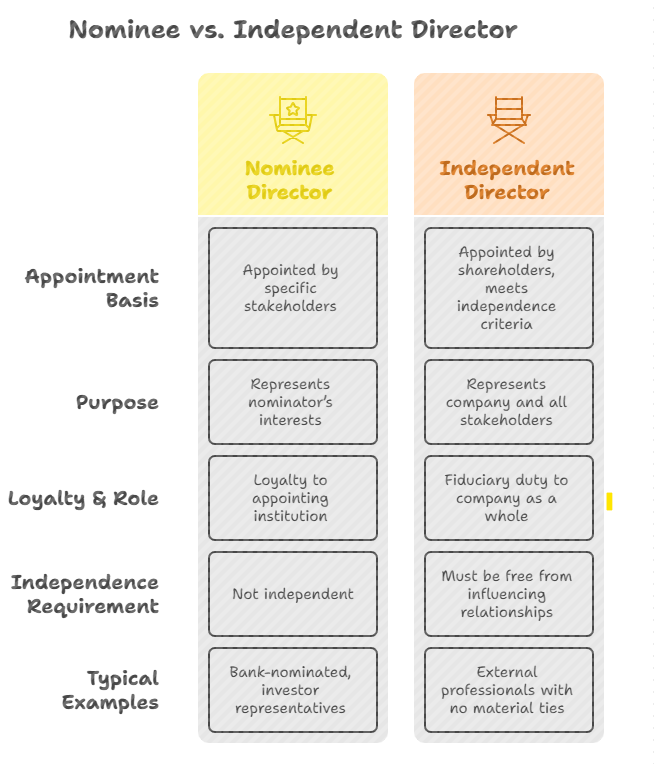

There’s significant confusion between independent directors and non-executive directors because both are not involved in day-to-day management. However, they’re distinct categories with different independence standards. A non-executive director is simply any director who doesn’t hold an executive position in the company—they’re not employees receiving salaries for operational roles. But non-executive directors can have other relationships with the company that independent directors cannot have.

Here’s the key distinction: all independent directors are non-executive directors, but not all non-executive directors are independent directors. A non-executive director might be a nominee of a major investor, a representative of a lending institution, a significant shareholder, or someone with business relationships to the company. These connections disqualify them from independent status even though they’re not executives.

For example, suppose a venture capital firm holds 15% of a company’s shares and appoints a partner from their firm to the board. That person is a non-executive director—they don’t work for the company operationally. But they’re not independent because they represent a specific stakeholder (the VC firm) and have a fiduciary duty to protect that stakeholder’s investment. Independent directors, by contrast, represent no specific stakeholder—they’re there to provide impartial oversight for the benefit of the company and all stakeholders collectively.

Independent director vs nominee director

Nominee directors are appointed by specific stakeholders to represent their interests on the board. Lenders often require nominee director rights as a condition of major loans, financial institutions appoint nominee directors to companies they’ve invested in, and government entities place nominee directors in companies where they hold stakes. These directors have clear mandates to protect the interests of those who nominated them.

The fundamental incompatibility with independence is obvious: nominee directors cannot be impartial when they’re explicitly appointed to advocate for particular interests. If a bank nominates you to a company’s board to protect the bank’s loan interests, you’re expected to scrutinize decisions that might affect loan repayment, potentially oppose actions that increase financial risk to the bank, and generally ensure the bank’s interests are considered. This advocacy role is the opposite of the independent director’s obligation to evaluate decisions purely on company-wide merit.

Section 149(6) explicitly states that independent directors cannot be nominee directors. This isn’t just a technical distinction—it reflects fundamental differences in role and loyalty. Nominee directors serve important governance functions by ensuring major stakeholders have board-level visibility into company decisions, but that function is different from the independent oversight role. Companies typically have both nominee directors (representing specific interests) and independent directors (providing impartial oversight), with each serving distinct governance purposes.

Independent director vs managing/whole-time director

The distinction between independent directors and managing directors or whole-time directors is the clearest of all director category differences. Managing directors and whole-time directors are employees of the company. They receive salaries, have employment contracts, report to the board, and are responsible for implementing board decisions and running daily operations. They’re insiders with deep company knowledge and operational authority.

Independent directors, by definition under Section 149(6), cannot be managing directors or whole-time directors. The roles are mutually exclusive. You cannot simultaneously be part of the management team being overseen and provide independent oversight of that team. Managing directors are evaluated by the board on their performance—independent directors are the ones doing that evaluation. This fundamental structural separation is essential to corporate governance.

The practical implications matter for appointment decisions. If your company’s CFO wants to become an independent director after leaving the position, they cannot do so immediately. They must wait through the three-year cooling-off period required under Section 149(6)(e) before they can be considered for independent director status. Similarly, if an independent director is offered a whole-time director position, accepting it immediately terminates their independent director status—the roles cannot coexist.

Which companies must appoint independent directors?

Requirements for listed public companies

Every listed public company must have at least one-third of its total number of directors as independent directors, according to Section 149(4) of the Companies Act 2013. This is a mandatory minimum—the company cannot operate with a lower proportion of independent directors without violating the law. If the calculation results in a fraction, it must be rounded up to the nearest whole number.

Here’s how the math works: if your listed company has a board of 9 directors, one-third equals 3 independent directors exactly. If you have 10 directors, one-third is 3.33, which rounds up to 4 required independent directors. If you have 8 directors, one-third is 2.67, rounding up to 3. This rounding-up rule ensures companies cannot avoid the requirement by keeping board sizes that would otherwise result in fractional independent director requirements.

Additionally, SEBI LODR Regulation 17(1)(b) adds further composition requirements. If the chairman is a non-executive director, at least one-third of the board must be independent directors (same as Companies Act).

However, if the company doesn’t have a regular non-executive chairman, at least half the board must comprise independent directors. This higher threshold for companies without non-executive chairmen reflects SEBI’s concern that executive chairmen need stronger independent oversight to prevent excessive management influence over board decisions.

Requirements for unlisted public companies

For unlisted public companies, the requirement is more targeted. Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 specifies that certain classes of unlisted public companies must have at least 2 independent directors. This is a lower threshold than listed companies face, reflecting the different stakeholder profiles and regulatory expectations for companies without public market investors.

The mandatory appointment trigger is based on meeting any one of three financial thresholds measured as of the last date of the latest audited financial statements. If your unlisted public company crosses any of these thresholds, you must appoint at least 2 independent directors within the prescribed timeline. The three triggers operate independently—meeting just one is sufficient to activate the requirement.

Important exceptions exist. The independent director requirement does not apply to unlisted public companies that are joint ventures, wholly-owned subsidiaries, or dormant companies, even if they meet the financial thresholds. Additionally, if a company ceases to meet all three threshold criteria for three consecutive years, it’s no longer required to maintain independent directors until it again crosses one of the thresholds.

Paid-up share capital threshold

The first trigger is paid-up share capital of ₹10 crore or more. If your unlisted public company has paid-up capital that equals or exceeds this threshold on the last date of your latest audited financial statements, you must appoint at least 2 independent directors. This threshold targets companies with substantial equity capitalization, regardless of their operational scale.

Paid-up capital is the actual amount shareholders have paid for shares, not the authorized capital in your Memorandum of Association. If your company has authorized capital of ₹20 crore but only ₹8 crore has been called up and paid by shareholders, you’re below the threshold. However, once paid-up capital reaches ₹10 crore, the requirement activates.

The measurement date matters significantly. The assessment is based on the last date of your latest audited financial statements, typically March 31 for companies following April-March financial years. If you cross ₹10 crore paid-up capital mid-year, you’re not immediately required to appoint independent directors—the requirement kicks in once your year-end audited statements reflect the higher paid-up capital. However, once triggered, you must complete appointments within the reasonable implementation period.

Turnover threshold

The second trigger is annual turnover of ₹100 crore or more. This targets operationally large companies even if their paid-up capital is modest. Many businesses operate with relatively small equity bases but generate substantial revenues—these companies need independent director oversight due to their economic significance and stakeholder impact.

Turnover means total revenue from operations as reflected in your profit and loss statement. For companies following Indian Accounting Standards, this would be revenue from operations as per Schedule III to the Companies Act. It includes sales of goods, rendering of services, and other operating revenues, but typically excludes other income like interest received or profit on sale of assets unless those are your core business activities.

Like the paid-up capital threshold, turnover is assessed based on your latest audited financial statements. If your FY 2024-25 audited statements show turnover of ₹105 crore, the independent director requirement applies even if your FY 2023-24 turnover was only ₹95 crore. The threshold assessment happens annually based on audited financials, and once you cross it, you must ensure compliance with the independent director appointment requirement.

Outstanding loans and deposits threshold

The third trigger is aggregate outstanding loans, debentures, and deposits exceeding ₹50 crore. This targets companies with significant borrowings or public deposits, recognizing that creditor protection requires independent oversight. When a company owes substantial amounts to lenders and depositors, having independent directors helps ensure management doesn’t take excessive risks or favor shareholder interests at creditor expense.

The calculation aggregates three categories: loans from banks and financial institutions, debentures issued to investors, and deposits accepted from the public or others. All three are added together, and if the total exceeds ₹50 crore as of your financial year-end, the requirement is triggered. This isn’t about total borrowing capacity or sanctioned limits—it’s about actual outstanding principal amounts owed on the statement date.

Notably, this is the lowest monetary threshold among the three triggers at ₹50 crore, compared to ₹10 crore for paid-up capital and ₹100 crore for turnover. The lower threshold reflects the regulatory priority on protecting creditor interests. Even relatively smaller companies with substantial debt burdens must have independent directors to provide oversight of financial management and ensure borrowings are used prudently rather than diverted to related parties or speculative ventures.

Exemptions for joint ventures and wholly-owned subsidiaries

Even if an unlisted public company meets one or more of the financial thresholds, it’s exempted from independent director requirements if it falls into specific structural categories. Joint ventures, wholly-owned subsidiaries, and dormant companies don’t need independent directors regardless of their financial size. These exemptions reflect practical realities of corporate structures and risk profiles.

Wholly-owned subsidiaries are exempted because they’re completely controlled by their holding companies. The holding company’s board, which presumably includes independent directors if required, provides oversight of subsidiary operations. Requiring subsidiaries to appoint their own independent directors would create redundant governance layers without adding meaningful oversight—the real control and decision-making happens at the holding company level. As long as the holding company has appropriate governance, subsidiary-level independent directors add limited value.

Joint ventures are partnerships between two or more entities, typically governed by shareholder agreements that specify each partner’s rights and obligations. These agreements usually include specific governance mechanisms, board composition requirements, and decision-making processes negotiated between the partners. Imposing statutory independent director requirements could conflict with carefully negotiated joint venture terms and isn’t necessary since each partner monitors the venture to protect their interests. Dormant companies by definition have no significant accounting transactions and are inactive, making independent director oversight unnecessary for entities that aren’t actually operating.

What disqualifies a person from being an independent director?

Promoter or relative connections

Being a promoter or related to promoters is an absolute disqualification with no exceptions or materiality thresholds. Under Section 149(6)(b), if you are or were a promoter of the company, its holding company, subsidiary, or associate company at any point in history, you permanently cannot serve as an independent director. Similarly, if you’re related to any promoter or director in this company group, you’re disqualified.

The promoter restriction makes intuitive sense—promoters are the company’s founders, typically its largest shareholders and controlling forces. They shaped the company’s strategy, culture, and management team. Someone with this level of historical involvement cannot credibly provide independent oversight. Even if decades have passed since someone was a promoter, that foundational role creates permanent disqualification from independent director status.

The relative restriction prevents circumventing independence requirements through family appointments. The Companies Act defines “relative” under Section 2(77) to include spouses, children, parents, siblings, and extended family members. If the company’s founder tries to appoint his daughter as an independent director, that appointment violates the law regardless of her professional qualifications. The relationship to the promoter disqualifies her completely.

Significant pecuniary relationships

Pecuniary relationships become disqualifying when they create financial dependencies that could influence your judgment. Under Section 149(6)(c), you’re disqualified if you have or had pecuniary relationships with the company beyond director’s remuneration and minor transactions (less than 10% of your income) during the two preceding financial years or current year.

Here’s what this means practically: if you’re a consultant billing the company ₹15 lakh annually and your total professional income is ₹80 lakh, that’s 18.75% of your income—well above the 10% threshold, making you ineligible for independent director status. Similarly, if you own property leased to the company generating ₹8 lakh annual rent against your total income of ₹50 lakh (16% of income), you’re disqualified.

The disqualification operates prospectively and retrospectively. You cannot be appointed if such relationships existed during the lookback period, and if you develop such relationships after appointment, you must immediately inform the board and your independent director status is compromised. This ongoing compliance obligation means you need continuous awareness of your financial relationships with the company throughout your tenure.

Recent employment history

Previous employment with the company or its group creates disqualifications based on cooling-off periods. Section 149(6)(e)(i) prohibits appointment if you or your relatives were key managerial personnel or employees of the company group in any of the three financial years immediately preceding your proposed appointment year. This three-year waiting period is firm—there’s no discretion for “exceptional circumstances” or “different role” arguments.

The KMP restriction is straightforward: if you were the company’s CEO, CFO, or company secretary anytime in the past three years, you cannot be appointed as an independent director. The reasoning is clear—someone who recently held top management positions has insider knowledge, ongoing relationships with current management, and may have participated in decisions they’d now oversee. Independence requires adequate separation from these internal dynamics.

The broader employee restriction covers any employment relationship, not just senior positions. If you worked in the company’s marketing department three years ago, you’re still within the cooling-off period. However, there’s a critical carve-out: the restriction doesn’t apply to relatives who were regular employees (not KMPs). Your nephew working as an engineer at the company doesn’t disqualify you, but if your nephew was the CFO, that relationship would disqualify you under the relative-KMP restriction.

Professional service relationships

Professional service relationships create disqualifications when you or your firm provided audit, legal, or consulting services to the company. Section 149(6)(e)(ii) establishes three-year cooling-off periods for these relationships, recognizing that professional service providers develop financial dependencies and inside knowledge that compromise independence.

For audit relationships (statutory audit, cost audit, or secretarial audit), any service provision during the three preceding financial years is disqualifying. There’s no materiality threshold—even a single audit engagement three years ago disqualifies you. The absolute prohibition reflects the special fiduciary position auditors occupy. You cannot independently oversee financial reporting that you previously certified or audit processes you previously conducted.

Legal and consulting relationships use a materiality test: you’re disqualified only if the firm had transactions with the company amounting to 10% or more of the firm’s gross turnover during the three-year lookback period. This recognizes that large professional service firms may have incidental relationships with hundreds of companies. However, once the company becomes a significant client generating 10% or more of your firm’s revenues, that dependency is material enough to compromise independence. The disqualification continues for three years after the service relationship ends.

Shareholding beyond permitted limits

Shareholding restrictions operate at two levels: your relatives’ holdings and your combined holdings with relatives. Under Section 149(6)(d)(i), your relatives cannot hold shares exceeding ₹50 lakh face value or 2% of paid-up capital (whichever is lower). Under Section 149(6)(e)(iii), you together with your relatives cannot hold 2% or more of total voting power.

The relative shareholding limit uses face value calculations on a “lower of” basis. If the company has ₹100 crore paid-up capital, 2% would be ₹2 crore, but the ₹50 lakh cap applies. If the company has ₹20 crore paid-up capital, 2% is ₹40 lakh, which is lower than ₹50 lakh, so ₹40 lakh becomes the operative limit. This ensures both very large and very small companies cannot circumvent independence through shareholding structures.

The combined voting power limit is a bright-line rule at 2%. Once you and your relatives collectively control 2% or more of votes, you’re disqualified regardless of other factors. This calculation requires attention to share class structures—if the company has differential voting rights shares, you must calculate based on actual voting power, not just equity percentage. The moment your combined shareholding crosses this threshold, independence is compromised and you must disclose this status change to the board.

Practical disqualification scenarios and examples

Let me walk you through specific real-world scenarios that illustrate how these restrictions operate in practice. These examples help you understand where the lines are drawn between permissible relationships and disqualifying connections.

Scenario 1: Ms. Sharma was CFO of ABC Limited until March 2023. Can she be appointed as an independent director of ABC Limited in May 2025?

Answer: No. She doesn’t meet the two-year cooling-off period under Section 149(6)(e)(i). Since she was a KMP in FY 2022-23, and the appointment is being considered in FY 2025-26 (only two years later), she’s still within the three-year lookback period. She can be considered after April 2026.

Scenario 2: Mr. Patel provides legal consulting services to XYZ Limited worth ₹12 lakh annually. His total professional income is ₹60 lakh. Can he be an independent director of XYZ Limited?

Answer: No. The ₹12 lakh represents 20% of his total income, exceeding the 10% threshold under Section 149(6)(c). Even though he’s not an employee and provides services through his professional capacity, this pecuniary relationship is material enough to disqualify independence.

Scenario 3: Mrs. Gupta’s husband holds 1.8% of voting shares in DEF Limited. Can she serve as an independent director?

Answer: Yes, with careful monitoring. The 1.8% is below the 2% threshold under Section 149(6)(e)(iii). However, this is very close to the limit. If her husband acquires even a small additional shareholding that pushes their combined holding above 2%, Mrs. Gupta must immediately inform the board as her independence would be compromised.

Scenario 4: Mr. Kumar’s son works as a senior manager at LMN Limited. Can Mr. Kumar be appointed as an independent director?

Answer: Yes. The employment restriction under Section 149(6)(e)(i) has a carve-out: it doesn’t apply to relatives who are regular employees (not KMPs). Since the son is a senior manager but not CEO, CFO, or company secretary, this relationship doesn’t disqualify Mr. Kumar. However, if the son were promoted to CFO, that would trigger disqualification.

Scenario 5: Ms. Reddy runs a training company that conducts employee development programs for PQR Limited worth ₹8 lakh annually. Her training company has total revenues of ₹75 lakh. Can she be an independent director?

Answer: Borderline, requires detailed evaluation. The ₹8 lakh represents 10.67% of her company’s revenues, just exceeding the 10% threshold under Section 149(6)(e)(ii)(B) for consulting firms. However, this depends on characterizing her services as “consulting” versus routine commercial transactions. If treated as consulting, the relationship disqualifies her. This scenario requires legal advice on proper classification.

What are the IICA databank requirements?

Databank registration process

Rule 6 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 requires individuals who intend to be appointed as independent directors to register with the Independent Directors Databank maintained by the Indian Institute of Corporate Affairs (IICA). This isn’t optional—it’s a mandatory prerequisite for independent director appointments. Before you can accept an independent director position, you must have your name included in this databank.

The registration process involves submitting an application to IICA through their online portal at www.iica.in. You’ll need to provide personal details, professional qualifications, work experience, and declarations confirming you meet the eligibility criteria under Section 149(6). The application requires uploading supporting documents proving your educational qualifications and professional background. IICA reviews applications to verify you meet baseline eligibility before adding your name to the databank.

Once registered, you receive a unique identification number that companies must verify when appointing you as an independent director. The databank serves multiple purposes:

- it creates a pool of qualified individuals available for independent director positions,

- helps companies identify suitable candidates, and

- provides regulatory authorities with a centralized record of independent directors across the corporate sector.

Your registration remains valid as long as you maintain active independent director status and comply with ongoing requirements.

If you’re exploring how to meet eligibility and registration conditions, here’s a detailed guide on how to become an independent director.

Online proficiency self-assessment test

Beyond databank registration, you must pass an online proficiency self-assessment test conducted by IICA within two year of your name being added to the databank. This test evaluates your understanding of Companies Act provisions, corporate governance principles, independent director roles and responsibilities, and relevant regulatory frameworks. The exam ensures independent directors have baseline knowledge necessary to fulfill their oversight functions effectively.

The test format is typically multiple-choice questions covering topics like board responsibilities, audit committee functions, related party transaction oversight, financial statement basics, and ethical conduct requirements. IICA provides study materials and reference guides to help candidates prepare. There’s no limit on the number of attempts—if you don’t pass on your first try, you can retake the test until you succeed.

You can learn more about the format, syllabus, and requirements for the independent director exam here.

Here’s the critical compliance point: you must pass this test within two year from the date your name was added to the databank. If you fail to pass within this two-year window, IICA removes your name from the databank. Once removed, you cannot continue as an independent director in any company until you re-register, pass the test, and have your name restored to the databank. This creates a strong incentive to prioritize test completion promptly after registration.

Several institutions also offer a structured independent director course designed to help you clear the IICA proficiency test and understand boardroom dynamics.

Exemptions from the test requirement

Not every individual is required to take the online proficiency test.

Rule 6(4) of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 provides exemptions for individuals with substantial professional or board-level experience.

Specifically, an individual is exempt if they have served for a total period of not less than three years as a director or key managerial personnel in:

- a listed public company,

- an unlisted public company with paid-up share capital of ₹10 crore or more,

- a body corporate listed in a FATF-member jurisdiction,

- a foreign body corporate with paid-up capital of at least USD 2 million, or

- a statutory corporation set up under an Act carrying on commercial activities.

The three years’ experience can be cumulative, even if gained across multiple eligible entities.

Additionally, individuals who have been advocates, chartered accountants, cost accountants, or company secretaries in practice for at least ten years are also exempt from the test.

Timeline and compliance obligations

The timeline compliance requirements create specific deadlines you must meet to maintain independent director status.

First, before accepting any independent director appointment, you must have already applied to IICA for databank inclusion. Companies appointing independent directors are required to verify that the appointee’s name appears in the IICA databank—appointments made without this verification violate regulatory requirements.

Second, within two years of your name being added to the databank, you must pass the proficiency self-assessment test unless you qualify for an exemption. The two-years period starts from your databank registration date, not your appointment date at any specific company. If you’re appointed as an independent director at three different companies within six months of databank registration, all three appointments are contingent on you passing the test within the original two-year deadline.

Third, you must maintain your databank registration throughout your tenure as an independent director. If your name is removed from the databank for any reason—whether failure to pass the test within two years, non-renewal of registration, voluntary withdrawal, or disciplinary action—you must immediately inform all companies where you serve as an independent director. Your continued service as an independent director becomes legally questionable once databank registration lapses, potentially exposing both you and the companies to compliance violations.

What is the declaration requirement for independent directors?

Initial declaration at first board meeting

Section 149(7) of the Companies Act 2013 requires every independent director to give a declaration confirming they meet the criteria of independence at the first meeting of the board in which they participate as a director.

This initial declaration is mandatory—you cannot simply assume your independence is understood from your appointment letter or board resolution. You must affirmatively declare your status in writing at your first board meeting.

The declaration should state that you meet all the criteria specified in Section 149(6) and are not aware of any circumstance or situation that exists or may be reasonably anticipated that could impair or impact your ability to discharge duties with objective independent judgment and without any external influence. This language comes directly from SEBI LODR requirements and represents best practice for comprehensive independence declarations.

The declaration must be recorded in the minutes of the board meeting.

The board then has an obligation under Section 149(7) read with SEBI LODR Regulation 25(8) to take the declaration on record after undertaking due assessment of its veracity. The board cannot simply accept your declaration at face value—directors must actively evaluate whether your stated independence is credible given what they know about your background, relationships, and circumstances.

This creates a two-step process: you declare independence, and the board validates that declaration.

Annual declaration requirement

Independence isn’t a one-time determination—it must be reaffirmed annually. Section 149(7) requires independent directors to give a fresh declaration at the first meeting of the board in every financial year confirming they continue to meet independence criteria. This annual recertification ensures ongoing compliance and creates regular checkpoints for evaluating whether circumstances have changed.

The annual declaration requirement recognizes that relationships and circumstances evolve. You might qualify as independent when initially appointed, but subsequently develop a pecuniary relationship that compromises independence. Your relative might acquire significant shareholdings, or you might take on a consulting engagement that crosses the 10% income threshold. The annual declaration forces you to reassess your status each year and make fresh declarations reflecting current circumstances.

For companies following April-March financial years, the annual declaration typically occurs at the first board meeting after April 1st. If that meeting is scheduled for May 15th, you’d provide your annual independence declaration at that meeting. The board again takes this declaration on record and assesses its veracity, creating an annual governance checkpoint where independence status is formally reviewed and documented.

Declaration upon change in circumstances

Beyond initial and annual declarations, independent directors must provide declarations whenever circumstances change that affect independence status. Section 149(7) explicitly requires declarations “whenever there is any change in the circumstances which may affect his status as an independent director.” This ongoing obligation means you cannot wait until the next annual declaration if something material changes mid-year.

What triggers this interim declaration requirement? Any event that impacts your independence criteria: you take on a consulting assignment with the company, your spouse acquires shares that push combined holdings above 2%, you’re appointed to the board of another company creating a cross-directorship conflict under SEBI rules, your firm begins providing legal services to the company exceeding materiality thresholds, or you learn that a relative has become indebted to the company beyond permitted limits.

The timing is critical: Schedule IV to the Companies Act states that “where circumstances arise which make an independent director lose his independence, the independent director must immediately inform the Board accordingly.” “Immediately” means as soon as you become aware of the disqualifying circumstance, not at the next scheduled board meeting. You should inform the board in writing promptly, and the matter should be formally addressed at the next board meeting with appropriate resolution—whether that means resigning from independent director status, moving to a different director category if permissible, or resolving the conflicting relationship.

Conclusion

Understanding who qualifies as an independent director requires navigating a complex dual regulatory framework that examines every facet of your relationships with the company.

The definition goes far beyond “not being an employee”—it scrutinizes your financial ties, your relatives’ dealings, your professional service history, your shareholdings, and even your involvement with non-profit organizations connected to the company.

The key takeaway is this: independence is both comprehensive and ongoing. You must clear multiple criteria hurdles under Section 149(6) of the Companies Act 2013, and if you’re joining a listed company, you face additional restrictions under SEBI LODR Regulation 16(1)(b).

Your independence status isn’t determined once at appointment and then forgotten—it requires annual reaffirmation and immediate disclosure if circumstances change. The IICA databank registration and proficiency test add procedural compliance layers that cannot be ignored.

For companies appointing independent directors, thorough due diligence is essential. Don’t rely on candidates’ self-assessments alone—verify their promoter connections, quantify their pecuniary relationships, check their relatives’ shareholdings, calculate their firm’s revenue dependency on your company, and confirm databank registration status. For professionals considering independent director roles, carefully evaluate whether you truly meet all criteria before accepting appointments. The consequences of failing independence requirements include potential removal, regulatory scrutiny, and reputational damage.

The regulatory investment in defining and enforcing independence standards reflects how critical this role is to corporate governance. Independent directors protect minority shareholders, provide checks on management excess, bring objective perspectives to strategic decisions, and maintain the integrity of financial reporting. When independence is genuine, these governance benefits are real. When independence is compromised through hidden relationships or inadequate vetting, the entire governance structure weakens. Use this guide’s detailed criteria breakdown and practical examples to ensure independence is genuine, not just apparent.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a company secretary be appointed as an independent director in the same company?

No. A company secretary is a whole-time employee and key managerial personnel of the company. Section 149(6)(e)(i) disqualifies current KMPs from independent director status. However, a practicing company secretary can be appointed as an independent director in other companies where they don’t serve as company secretary.

What is the minimum age to be appointed as an independent director?

Under the Companies Act 2013, the minimum age is 18 years (general director eligibility). However, for listed companies under SEBI LODR Regulations, the minimum age is 21 years and maximum age is 70 years, with extensions possible through special resolutions.

Can a relative of a promoter ever qualify as an independent director?

No. Section 149(6)(b)(ii) explicitly disqualifies anyone related to promoters or directors of the company or its group companies. This is an absolute prohibition with no exceptions, regardless of the relative’s professional qualifications or lack of active involvement with the promoter.

Does the independent director definition differ between Companies Act and SEBI regulations?

Yes. SEBI LODR Regulation 16(1)(b) imposes additional restrictions beyond the Companies Act for listed companies, including cross-directorship prohibitions and material business relationship restrictions. Listed company independent directors must satisfy both frameworks simultaneously—Companies Act provides the baseline and SEBI adds supplementary requirements.

What happens if an independent director loses their independence during tenure?

They must immediately inform the board under Schedule IV of the Companies Act. The board should take on record this disclosure and address the status change—typically resulting in resignation from independent director position or, if permissible, continuation in a different director category.

Can a former employee of a company become an independent director?

Yes, but only after a three-year cooling-off period. Section 149(6)(e)(i) prohibits appointment if you were an employee or KMP in any of the three financial years immediately preceding the year of proposed appointment. After three full financial years have passed, the disqualification lapses.

How long is the cooling-off period after being a Key Managerial Personnel?

Three financial years. If you were a KMP (CEO, CFO, or company secretary) of the company or its group, you cannot be appointed as an independent director until three complete financial years have passed since you left that position, as per Section 149(6)(e)(i).

Are independent directors liable for company violations?

Only for acts occurring with their knowledge, consent, or connivance, or where they failed to act diligently, according to Section 149(12). Independent directors have limited liability compared to executive directors—they’re not automatically liable for all company violations unless they knowingly participated or failed in their oversight duties.

Can an independent director hold shares in the company?

Yes, but only within limits. An independent director can hold shares in the company, provided that together with relatives, such holdings do not exceed 2% of the total voting power, as per Section 149(6)(e)(iii) of the Companies Act, 2013.

What pecuniary relationships are permitted for independent directors?

Director’s remuneration is always permitted. Additionally, other transactions are allowed if they don’t exceed 10% of your total income during the two preceding financial years or current year, as per Section 149(6)(c). Beyond these exemptions, pecuniary relationships with the company are disqualifying.

Is IICA databank registration mandatory for all independent directors?

Yes. Rule 6 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 requires individuals to register with IICA’s Independent Directors Databank before appointment. Additionally, they must pass the online proficiency test within two year of registration, unless exempted based on experience.

Can an independent director serve in multiple companies simultaneously?

Yes, but with limits. An independent director can serve in maximum seven listed companies. If the person is a whole-time director in any listed company, they can serve as independent director in maximum three listed companies, as per SEBI LODR Regulation 17A(1).

What is the difference between an independent director and an outside director?

Outside director is a broader term for any director not employed by the company. Independent director is a specific category with strict eligibility criteria under Section 149(6). All independent directors are outside directors, but not all outside directors qualify as independent—some may be nominee directors or have relationships that disqualify independence.

Do independent director requirements apply to private companies?

No. Section 149(4) and Rule 4 apply only to public companies (listed or certain large unlisted public companies). Private limited companies have no statutory requirement to appoint independent directors, though they may voluntarily choose to do so for governance purposes.

Can a practicing professional be appointed as an independent director?

Yes, practicing professionals like chartered accountants, company secretaries, or lawyers can serve as independent directors in companies where they don’t provide professional services. However, Section 149(6)(e)(ii) prohibits appointment if you or your firm provided audit, legal, or consulting services to the company in the three preceding financial years.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications