Comprehensive guide to patents in India covering Patent Act 1970, types, filing process, rights, infringement remedies, and litigation. Learn everything about protecting your inventions.

Table of Contents

What is a Patent?

What if I told you that a single idea, something you sketch on a napkin or develop in a lab, could become a legally protected asset worth crores?

That’s the power of a patent.

Whether you’re an inventor, entrepreneur, startup founder, or legal professional, understanding how patents work isn’t optional; it’s essential. In today’s innovation-driven economy, patents are the invisible engines powering billion-dollar businesses and shaping global technology competition.

Think about it: every breakthrough you’ve ever heard of, life-saving drugs, smartphone cameras, AI algorithms, electric vehicles, exists in a fiercely competitive world protected by patents. Behind each of these innovations is not just an idea, but a strategic decision to secure ownership before anyone else can copy it.

Why does it matter to you?

In India, innovation is exploding. The number of patent applications is increasing every year. Startups and research institutions are investing heavily in R&D, and global companies are expanding their patent portfolios here.

Owning a patent doesn’t just protect your idea; it can attract investors, increase your company valuation, and give you a monopoly over your invention for 20 years.

And here’s the best part: patents don’t just benefit inventors. They create entire career ecosystems for scientists, engineers, lawyers, and business professionals who can navigate the intersection of technology and law.

Patent agents, patent attorneys, IP consultants, technology transfer officers, and R&D strategists all play crucial roles in this space. If you understand patents, you understand the language of innovation, and that gives you a major edge. You can leverage this, too!

What will you get from this guide?

This isn’t just a definition-based overview.

This is your complete roadmap to understanding patents: how they work, what can (and can’t) be patented, how to file and protect them in India, and how they shape industries and careers.

By the end of this guide, you’ll understand why it’s one of the most powerful tools for innovation, business growth, and professional advancement in today’s world. You will also understand how you can make a career out of it!

Ready to unlock the power of patents?

Let’s begin.

Patent Definition and Core Concepts

A patent is an exclusive right granted by the government to an inventor that allows them to prevent others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, or importing their invention for a limited period. Think of it as a legal monopoly that rewards innovation while eventually contributing to public knowledge.

Under Section 2(m) of the Patents Act, 1970, a patent is a government grant conferring exclusive rights upon the patentee for the claimed invention.

In India, patents give you the right to exclude others from exploiting your invention, not necessarily the right to use it yourself. This distinction matters because you might hold a patent that builds on someone else’s patented technology, requiring you to negotiate licenses with them before commercializing your invention.

The core concept behind patent protection is a bargain between society and inventors. You disclose your invention publicly in exchange for temporary exclusive rights, typically lasting 20 years from the filing date. After this period expires, your invention enters the public domain, where anyone can use it freely.

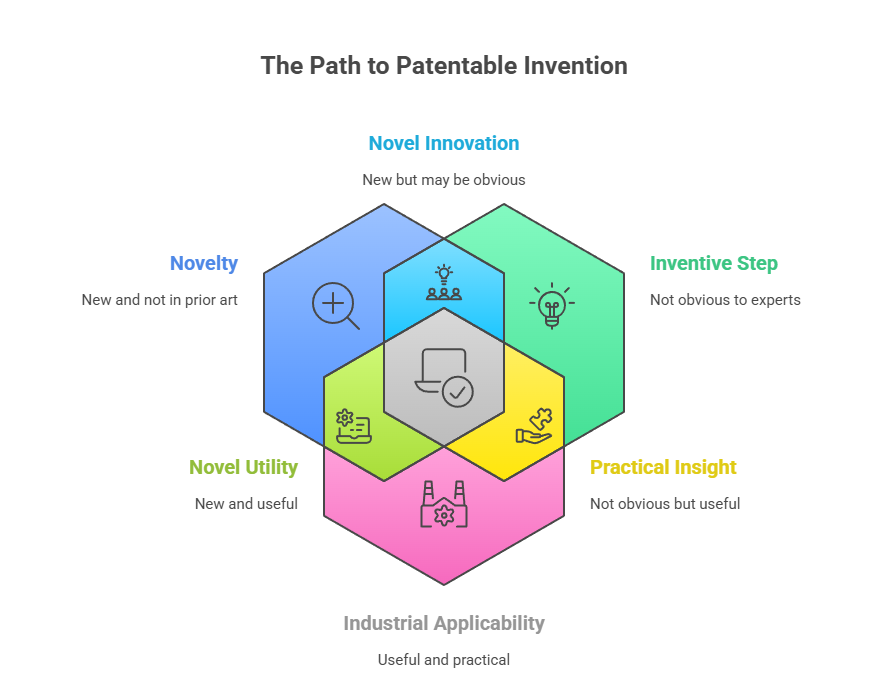

For a patent to be granted in India, your invention must meet three critical elements:

- novelty,

- inventive step, and

- industrial application.

How Do Patents Differ from Other Intellectual Property Rights?

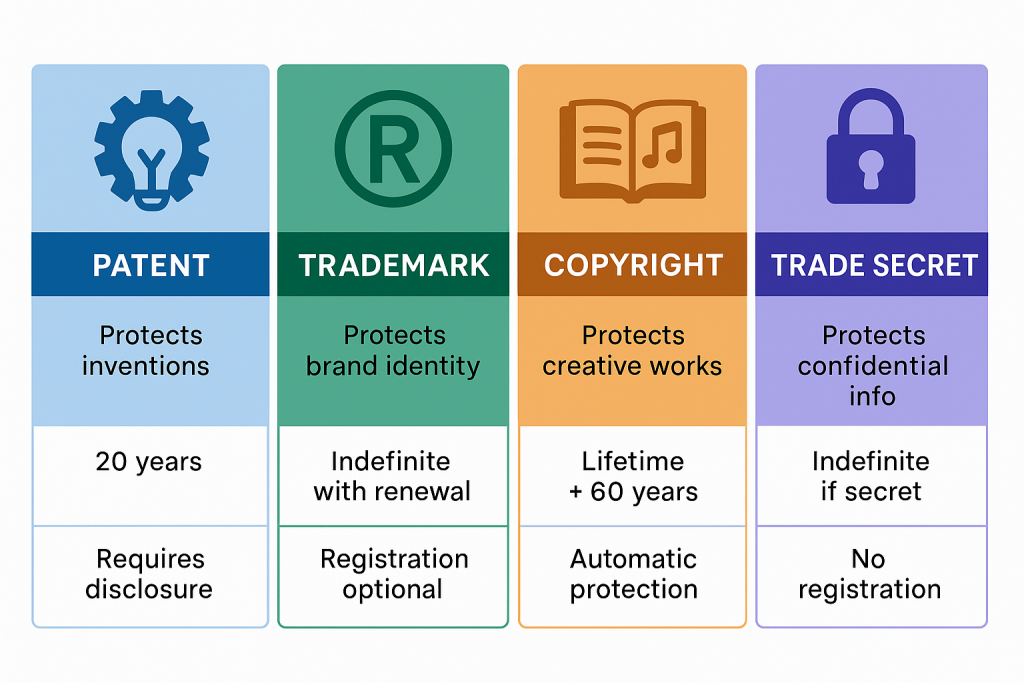

Patents protect functional inventions and processes, distinguishing them fundamentally from other forms of intellectual property.

- Patent – Protects how something works or a technical innovation. Example: A new type of battery that charges twice as fast as existing ones.

- Trademark – Protects brand identifiers such as names, logos, slogans, or symbols that distinguish goods or services. Example: The Nike “swoosh” logo or the name “Amul” for dairy products.

- Copyright – Protects original creative expressions in literary, artistic, or musical works, including software code. Example: A novel like Harry Potter, a song, or the source code of a mobile app.

In India, the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks handles both patents and trademarks, while copyright registration falls under the Copyright Office.

Trade secrets represent another alternative to patents. Unlike patents, which require public disclosure, trade secrets protect confidential business information as long as you keep it secret. The Coca-Cola formula exemplifies this approach; it’s never been patented because that would require revealing the recipe after 20 years.

The choice between these protections depends on your invention’s nature and your business strategy. If you’ve developed a manufacturing process that competitors could easily reverse-engineer once your product hits the market, a patent provides stronger protection than trade secrecy. Conversely, if you can maintain confidentiality indefinitely, trade secret protection might offer longer-term advantages.

Importance of Patents

Understanding why patents matter goes beyond legal compliance; it’s about recognizing how intellectual property shapes innovation, competition, and economic growth in modern economies.

Patents as Monopolies and Their Wider Benefits

A patent grants a monopoly for about 20 years in the country where it’s issued, giving the patent owner exclusive rights to exclude others from making or selling the invention. While “monopoly” often carries negative connotations, patent monopolies serve crucial economic and social functions that benefit society as a whole.

This temporary monopoly incentivizes innovation by allowing inventors to recoup their research and development investments. Developing a new pharmaceutical drug, for instance, can cost billions of dollars and take over a decade. Without patent protection, competitors could immediately copy successful drugs without bearing any development costs, eliminating the economic incentive for original research.

Patents also facilitate knowledge dissemination. Because patent applications require detailed disclosures of how inventions work, they create a vast public repository of technical information. Approximately 70-90% of technical information can only be found in patents, making them invaluable resources for researchers, engineers, and businesses seeking to avoid duplicating existing work or build upon prior innovations.

The public disclosure requirement ensures that even though you get exclusive commercial rights for 20 years, society gains immediate access to knowledge about your invention. This accelerates technological progress as other inventors can study your approach, understand what’s already been done, and develop improvements or alternative solutions.

How Patents Shape Business and Innovation

Patents fundamentally influence business strategy, investment decisions, and competitive dynamics across industries. For startups and entrepreneurs, patent portfolios often represent their most valuable assets, attracting investors who see protected intellectual property as reducing market risks and creating sustainable competitive advantages.

In technology-intensive sectors like pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and electronics, patents determine market leadership. Companies with strong patent portfolios can license their technology to others, generating revenue streams without manufacturing products themselves. Alternatively, they can use patents defensively to prevent competitors from blocking their market access.

Patents also drive collaboration and technology transfer. When you hold patents, you can negotiate licensing agreements that allow others to use your technology while you earn royalties. This creates ecosystems where multiple companies build products using licensed technology, expanding markets while ensuring you benefit from your innovation.

For research institutions and universities, patents enable technology commercialization. Academic researchers can patent their discoveries, then license them to companies with the resources to develop commercial products. This bridges the gap between basic research and market applications, ensuring scientific advances benefit society practically.

Legal Framework Governing Patents

India’s patent system operates under a comprehensive legal framework that balances innovation incentives with public interest, particularly in sectors critical to public health and national security.

Patent Act, 1970 and Its Objectives

The Indian Patent Act of 1970 came into force in 1972 and initially emphasized process patents rather than product patents in the pharmaceutical and agrochemical sectors. This approach was designed to ensure medicines could reach poor sections of society at affordable prices, allowing Indian companies to manufacture generic versions of drugs patented elsewhere by using different manufacturing processes.

The Indian Patent Act contains 23 chapters and 162 sections covering everything from what can be patented to enforcement procedures. Key chapters address patentability criteria, application procedures, examination processes, opposition mechanisms, and infringement remedies. Understanding this structure helps you navigate the system more effectively.

The Act underwent significant amendments in 1999, 2002, and 2005 to comply with international obligations under the WTO’s TRIPS Agreement.

Patents vs. Trademarks, Copyrights, Trade Secrets

While I have touched on IP differences earlier, understanding their relationship within India’s legal framework provides strategic insights for protecting your innovations comprehensively.

- Patents protect functional aspects of inventions; how things work, what they do, and how they’re made. The Patent Act, 1970, governs this protection exclusively. When you patent a new smartphone camera technology, you’re protecting the technical innovation that enables better image capture, not the phone’s brand name or its user interface design.

- Trademarks, governed by the Trade Marks Act, 1999, protect brand identifiers that distinguish your goods or services from competitors. Your smartphone’s brand name, logo, and distinctive design elements qualify for trademark protection. Unlike patents, which expire after 20 years, trademarks can last indefinitely with proper renewal and use.

- Copyrights, regulated under the Copyright Act, 1957, protect original creative works, including software code, user interface designs, and documentation. The same smartphone might have copyrighted software, user manuals, and artistic elements in its interface. Copyright protection arises automatically upon creation and typically lasts for the author’s lifetime plus 60 years.

- Trade secrets protect confidential business information under common law and the Information Technology Act, 2000. Your smartphone manufacturer might treat certain manufacturing techniques, customer data, or business strategies as trade secrets. Protection lasts as long as you maintain confidentiality, but you lose it immediately if the information becomes public.

Smart IP strategy often combines multiple protections. You might patent your smartphone’s innovative hardware, trademark its brand, copyright its software and documentation, and maintain manufacturing efficiencies as trade secrets. This layered approach creates comprehensive protection that’s harder for competitors to circumvent.

How Do International Treaties Influence Indian Patent Law?

India’s patent system doesn’t operate in isolation; it’s shaped by international agreements that facilitate global patent protection and harmonize standards across countries.

TRIPS Agreement Compliance and 2005 Amendments

India joined the World Trade Organization in 1994 and became a signatory to the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement, achieving complete compliance by 2004 through amendments implemented in 2005. This marked a fundamental shift in India’s patent philosophy and enforcement mechanisms.

TRIPS established minimum standards for intellectual property protection that all WTO member countries must follow. It required India to provide patent protection for inventions in all fields of technology, including pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals, for a term of 20 years from the filing date. Prior to TRIPS compliance, India’s process patent system allowed generic manufacturers to produce patented drugs using alternative methods.

The 2005 amendment introduced several critical changes to align with TRIPS. It extended product patents to critical areas like pharmaceuticals and chemicals, strengthening patent rights enforcement and encouraging both domestic and foreign investment in research and development. However, concerns arose about essential medicine prices potentially increasing under the new product patent regime.

To balance TRIPS compliance with public health needs, India incorporated safeguards, including compulsory licensing provisions. These allow the government to authorize generic manufacturers to produce patented medicines at affordable prices when public health demands it, particularly for diseases like HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and cancer.

PCT Filing Procedures and Benefits

The Patent Cooperation Treaty, adhered to by more than 150 countries including the United States and India, facilitates filing patent applications on the same invention in member countries by providing centralized filing procedures and a standardized application format. If you’re seeking protection across multiple countries, PCT offers significant advantages over filing separate applications in each jurisdiction.

Under PCT, you file a single international application designating countries where you want protection. This gives you an international filing date recognized in all designated countries, essentially reserving your priority date across jurisdictions. In India, for PCT applications, the 20-year patent term begins from the international filing date rather than the national filing date.

The PCT process includes an International Search Report and Written Opinion assessing your invention’s patentability based on prior art. This early feedback helps you evaluate whether pursuing national phase applications is worthwhile before incurring substantial costs in multiple countries. You can use this information to refine claims, abandon weak applications, or focus resources on jurisdictions where you’re likely to succeed.

Paris Convention Priority Rights Implementation

The Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, adhered to by 176 countries, including India, provides that each country guarantees to citizens of other member countries the same patent and trademark rights given to its own citizens. More importantly for patent strategy, it establishes the priority rights system that underpins international patent filing.

Priority rights mean that when you file a first patent application in one member country, you have 12 months to file corresponding applications in other member countries. These later applications are treated as if filed on the same date as your first application, protecting you from intervening prior art or competing applications filed during that 12-month period.

For example, if you file a patent application in India on January 1, 2025, and someone else independently develops and patents a similar invention in Germany on March 1, 2025, your subsequent German application filed by December 31, 2025, will take priority over their March filing. This is crucial because patent rights generally go to the first to file, not the first to invent.

Priority rights also mean your later applications won’t be invalidated by actions in between, such as publication or exploitation of the invention, sale of copies of the design, or use of the trademark. This allows you to test markets, present at conferences, or discuss your invention with potential partners after your first filing without destroying your patent rights in other countries.

In India, claiming Paris Convention priority requires filing certified copies of your foreign priority application and paying prescribed fees. The Indian Patent Office examines your priority claim to ensure it complies with formal requirements and that the Indian application’s subject matter was disclosed in the priority application.

Geographic Filing Considerations and PCT Strategies

Deciding where to seek patent protection requires strategic analysis of market potential, manufacturing locations, competitor presence, and enforcement capabilities. Not every country warrants the expense of obtaining and maintaining a patent.

Start by identifying countries where you’ll manufacture, sell, or license your invention. These represent your primary markets requiring protection. Next, consider where major competitors operate; getting patents in their jurisdictions can prevent them from practicing your invention or provide leverage for cross-licensing negotiations.

Manufacturing locations deserve special attention. Even if you don’t plan to sell in a particular country, if you or your licensees manufacture there, patent protection prevents competitors from reverse-engineering your product and exporting copies to markets you do serve. This is why China, India, and other manufacturing hubs often appear in patent portfolios regardless of their market size for the patented product.

PCT strategy requires balancing costs against uncertainties. The international phase costs are lower than national phase filings, but you’ll eventually pay national fees in each country you pursue. Use the 30-month window to gather market intelligence, assess competitor landscapes, and refine your business model before committing to national phases.

Consider regional patent systems where available. The European Patent Office allows you to obtain a single patent that can be validated in multiple European countries, though it eventually splits into national patents. For businesses targeting Europe, this provides cost savings over individual country filings while maintaining flexibility about which countries to validate after the grant.

What Are the Essential Elements That Make Something Patentable?

Understanding patentability requirements is crucial before investing time and resources in patent applications. Not everything qualifies for patent protection, and knowing these boundaries helps you evaluate whether your invention merits pursuing.

Scope of Patentable Inventions in India

Under the Patent Act, an invention is defined as a new product or process involving an inventive step and capable of industrial application. This three-part definition establishes the foundation for what can receive patent protection in India.

The Act broadly covers:

- utility patents protecting processes,

- machines,

- articles of manufacture, and

- compositions of matter.

A process might be a new manufacturing method, chemical synthesis route, or data processing algorithm with technical application.

Novelty Requirements and Prior Art Analysis

Novelty: For a patent to be issued, your invention must be new or “novel”—something not done before. Novelty is absolute in India, meaning your invention must be new, not just in India but globally. If anyone, anywhere in the world, has previously disclosed the same invention publicly, it destroys novelty and prevents patenting.

Prior Art: Prior art encompasses all information made available to the public before your patent application’s filing date (or priority date if you claim one). Prior art includes not just granted patents but any previous mention of the technology in the public domain, internet publications, research databases, conference presentations, and other spheres besides patents. A single journal article, conference poster, or YouTube video describing your invention constitutes prior art that can invalidate your patent.

This global novelty standard means conducting comprehensive prior art searches is essential before filing. Patent examiners conduct their own prior art searches during examination and may reject claims based on information not found in preliminary searches. Even obscure publications in foreign languages or technical documents from decades ago can constitute invalidating prior art if they disclose your invention.

Non-Obviousness Standards and Inventive Step

Patents require that inventions be “not obvious” as related to changes to something already invented. This non-obviousness requirement, called “inventive step” in Indian law, ensures patents reward genuine innovations rather than trivial modifications anyone skilled in the field could easily make.

Non-obviousness is one of the most difficult determinations to prove in the patent review process, with different examiners potentially reaching different conclusions about whether an invention represents an obvious leap from prior art. The standard considers what would be obvious to a person having ordinary skill in the relevant technical field at the time of your invention.

- One common approach examines whether combining prior art references to achieve your invention would have been obvious. If prior patents disclose all the elements of your invention, even in separate documents, and combining them would be straightforward for a skilled person, your invention likely lacks inventive step.

- Another consideration is whether your invention solves a long-felt need or achieves unexpected results. If people in your field have sought a solution to a problem for years without success, and your invention achieves it, this suggests non-obviousness. Similarly, if your invention produces benefits that wouldn’t be predicted from prior art, this supports inventive step.

- Secondary considerations include commercial success, skepticism from others before your invention, and copying by competitors after your invention became known.

While not dispositive, these factors provide circumstantial evidence that your invention wasn’t obvious; if it were, someone would have done it sooner.

Industrial Applicability and Utility Thresholds

Industrial applicability, defined in relation to an invention under the Patent Act, means capable of being made or used in an industry. This requirement ensures patents protect practical innovations rather than abstract theories or purely academic discoveries.

“Industry” should be understood in its broadest sense as including any useful, practical activity as distinct from purely intellectual or aesthetic activity, and doesn’t necessarily imply the use of a machine or the manufacture of an article. Agricultural methods, service industry processes, and even some business methods can satisfy industrial applicability if they have practical, useful applications.

The utility threshold is relatively low; your invention merely needs to work as described and provide some benefit. The invention must be able to be used (it must work and cannot just be a theory). You don’t need to prove your invention is the best solution or even a particularly good solution, just that it functions and serves a useful purpose.

If you can demonstrate that your invention operates as claimed and has at least one practical use, you generally satisfy this requirement.

Sufficient Disclosure and Enablement Criteria

A patent requires a clear description of how to make and use the invention. This disclosure requirement serves patent law’s fundamental bargain; you get exclusive rights in exchange for teaching the public how to practice your invention.

The specification must set forth the precise invention for which a patent is requested, distinguishing it from other inventions and from what is old, describing completely a specific embodiment, and explaining the best mode of carrying out the invention. “Best mode” means you must disclose the best way you know to practice your invention at the time of filing, not holding back superior techniques or conditions.

Enablement requires that someone skilled in your field could reproduce your invention using only your patent specification without undue experimentation. If critical steps are vague, if you omit important details, or if reproducing your invention would require extensive trial-and-error, your specification fails enablement. This doesn’t mean you must spoon-feed every minor detail, but the disclosure must be complete enough that a skilled practitioner can make and use your invention.

Comprehensive Patent Classification

Patents come in several varieties, each protecting different aspects of innovation. Understanding these classifications helps you choose the right protection strategy for your specific invention.

What Are the Main Types of Patents and Their Applications?

India’s patent system, like most jurisdictions, recognizes distinct patent types tailored to different categories of innovation. Selecting the appropriate type is crucial because each carries different requirements, examination standards, and protection scopes.

Utility Patents: Processes, Machines, Manufactures, Compositions

Utility patents may be granted for inventing a new or improved and useful process, machine, article of manufacture, or composition of matter. These represent the most common patent type, covering functional innovations across virtually all technical fields.

- Process patents: Process patents protect methods of doing something; manufacturing techniques, chemical synthesis routes, data processing algorithms, or therapeutic treatment methods. If you develop a new way to refine petroleum, a novel method for encrypting data, or an innovative process for 3D printing complex geometries, utility patents protect these inventions. If the patent is for a process, then the patentee has the right to prevent others from using the process, using the product directly obtained by the process, offering for sale, selling, or importing the product.

- Machine patents: This covers apparatus and devices with functional components. Industrial equipment, consumer electronics, medical devices, and robotics all typically receive protection as machine inventions. The key is that machines have structures that perform functions; they do something useful through their physical construction.

- Manufacture: Articles of manufacture encompass any man-made objects that aren’t machines or compositions of matter. Simple mechanical tools, furniture designs with functional elements, packaging innovations, and consumer products fall into this category. Even though they’re simpler than machines, articles of manufacture still require novelty, inventive step, and utility.

- Compositions: Compositions of matter include chemical compounds, pharmaceutical formulations, polymers, alloys, and any combinations of substances. This category is particularly important in pharmaceuticals, materials science, and chemical industries. If you discover a new chemical compound, develop a drug formulation with improved bioavailability, or create an alloy with superior properties, composition of matter patents protect these innovations.

Design Patents: Ornamental and Aesthetic Protection

Design patents may be granted for inventing a new, original, and ornamental design for an article of manufacture. In India, design protection actually falls under the Designs Act, 2000, rather than the Patent Act, but understanding design protection remains important for a comprehensive IP strategy. This distinction matters because design protection lasts 15 years and focuses on the ornamental appearance of functional items rather than how they work, while utility patents cover functional innovations for 20 years

Design protection focuses exclusively on aesthetic features, the visual appearance of objects, rather than how they function. The distinctive shape of a Coca-Cola bottle, the ornamental pattern on smartphone cases, or the unique appearance of furniture pieces exemplify design protection. A design patent number starts with a D and is protected for 15 years, a shorter term than utility patents, reflecting their ornamental rather than functional nature.

There are many products that combine functional and ornamental elements, potentially qualifying for both utility and design protection simultaneously.

Design protection offers distinct advantages in fashion, consumer products, and industries where appearance drives purchasing decisions. While utility patents require years to obtain, design registrations typically process more quickly. They also provide straightforward infringement analysis; if the accused product looks substantially similar to the protected design, infringement is likely established.

Plant Variety Protection

Plant patents may be granted for inventing or discovering and asexually reproducing any distinct and new variety of plant. This specialized patent category protects new plant varieties created through breeding, genetic engineering, or the discovery of useful mutations.

In India, plant variety protection operates primarily under the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Act, 2001 (PPVFR Act) rather than the Patent Act. However, understanding plant variety protection matters if you work in the agriculture, horticulture, or biotechnology sectors.

The PPVFR Act balances breeders’ rights with farmers’ rights, allowing farmers to save, use, and sell harvested material from protected varieties for their own use. This differs from standard patent protection and reflects India’s agricultural demographics and policy priorities. Breeders gain exclusive rights to produce, sell, and market seeds of new varieties, encouraging investment in developing improved crops.

Filing Strategies: Provisional and Non-Provisional Patents

Understanding when to file provisional versus complete applications significantly impacts your patent strategy, costs, and timeline. Each serves a different purpose in the patent process.

Balancing Filing Costs and Strategic Timing

A provisional specification is filed initially to secure a priority date for the invention and contains only a brief description without claims, while a complete specification follows the provisional filing and must be filed within a specified time (often 12 months) to convert a provisional application into a full-fledged patent application.

Provisional applications cost significantly less than complete applications because they require less detail and no formal claims. This makes them attractive when you want to establish a filing date but haven’t fully developed your invention or aren’t ready to invest in comprehensive patent drafting. You can file a provisional application describing your core innovation, then spend the next 12 months refining it, conducting market research, and determining whether full patent protection is worthwhile.

The strategic timing advantage is substantial. Once you file a provisional application, you can disclose your invention publicly, present it at conferences, discuss it with potential investors, or test market interest without destroying your patent rights. The provisional application’s filing date becomes your priority date, protecting you from intervening prior art or competing applications during that crucial first year.

However, provisional applications aren’t right for every situation. If your invention is fully developed, if competitors might be close to filing similar inventions, or if you need enforceable rights quickly, filing a complete application immediately may be preferable. Provisional applications don’t undergo examination and provide no enforceable rights—they merely reserve your priority date.

Key Considerations During the 12-Month Conversion Period

The 12-month period between filing a provisional application and the complete specification deadline is critical for making strategic decisions about your patent’s scope, markets, and business model. What should you do in these 12 months?

Prior Art Searches: Use this time to conduct comprehensive prior art searches. Your provisional application established priority, so any prior art discovered now won’t invalidate your rights as long as it predates your provisional filing. Armed with this knowledge, you can refine your claims to avoid prior art, focus on novel aspects, or decide to abandon the application if prior art makes patenting unlikely.

Market Testing: Market testing during this period provides invaluable feedback. Show your invention to potential customers, distributors, or strategic partners. Their responses help determine whether the investment in complete prosecution is justified. If market interest is strong, proceed with the complete specification. If the reception is lukewarm, you can abandon the provisional without incurring the substantial costs of full prosecution.

Improvements & Additions: The 12-month window also allows time to develop improvements or additional embodiments. Your complete specification can include these enhancements, broadening your protection beyond what the provisional disclosed. However, ensure new matter builds on the provisional’s disclosure—entirely new inventions may not be entitled to the provisional’s priority date.

Why is Establishing a Priority Date Important for Your Invention?

India, like most countries, operates on a first-to-file system. If you and a competitor independently develop the same invention, whoever files first generally gets the patent regardless of who invented it first. Your priority date establishes your position in this queue. Filing even a day earlier than a competitor can mean the difference between obtaining a valuable patent and being shut out entirely.

Priority dates also determine what constitutes prior art against your application. Any publication, patent, or public disclosure dated before your priority date is prior art that can invalidate your patent. Anything published after your priority date doesn’t affect your rights. This makes early filing crucial—every day you delay is another day that someone might publish information rendering your invention unpatentable.

For international patent families, priority dates enable Paris Convention and PCT benefits. Your first filing establishes a priority date that subsequent filings in other countries can claim. This protects you from intervening prior art and competing applications in those countries during the priority period. Without this mechanism, coordinating global patent protection would be nearly impossible.

Priority dates also affect patent term calculation. The term of every patent in India is 20 years from the date of filing the patent application, irrespective of whether it is filed with a provisional or a complete specification. Filing provisionally doesn’t extend your patent term—it expires 20 years from the provisional filing date, not from when you file the complete specification. This trade-off between early priority and patent term duration must be considered in your filing strategy.

What Inventions Cannot Be Patented Under Indian Law?

Understanding patent exclusions is as important as knowing what qualifies for protection. Indian patent law excludes certain categories of inventions to protect public interest, morality, and traditional knowledge.

Section 3 Exclusions: Mathematical Formulas, Business Methods

Sections 3 and 4 of the Patent Act prescribe specific subject matters that are not patentable under the Act. Section 3 contains numerous exclusions that shape India’s patent landscape significantly.

Examples of non-patentable subject matter include inventions contrary to public order or morality, mere discovery of a new form of a known substance without enhancement of known efficacy, and mere discovery of a new use of a known substance or the mere use of a known process. Each exclusion serves specific policy objectives.

Mathematical formulas, scientific principles, and abstract algorithms cannot be patented because they constitute basic knowledge that should remain freely available. If someone could patent E=mc², it would impede scientific progress and innovation. However, practical applications of mathematical methods or algorithms can be patentable if they solve technical problems and produce tangible results.

Business methods face stricter scrutiny in India than in the United States. Pure business method patents, strategies for conducting business without technical implementation, are generally not patentable.

However, business methods implemented through technical means or computer systems may qualify for protection if they solve technical problems and demonstrate inventive step.

Software Patentability: Per Se vs. Technical Effect in India

Software patentability in India occupies a gray area that has evolved through judicial interpretation. The subject matter that can be protected by patents is vast and varied, with even some methods of doing business potentially patentable, but computer programs “per se” are explicitly excluded under Section 3(k) of the Patent Act, 1970.

The “per se” exclusion means software cannot be patented simply for being software. However, software that produces a technical effect beyond the program’s normal operation or that solves a technical problem may qualify for protection. This “technical effect” test examines whether the software makes a technical contribution to the art.

For example, software that merely automates a business process likely fails this test—the technical contribution is just the general-purpose computer running the program. However, software that improves computer functionality, controls hardware more efficiently, processes data in novel ways, producing technical results, or solves technical problems in other fields may be patentable.

Indian courts have gradually clarified software patentability through cases examining whether inventions are “computer programs per se” or technical inventions implemented in software. The key distinction is whether the claims focus on the computer program itself or on the technical problem solved through software implementation.

Pharmaceutical Evergreening Restrictions

Section 3(d) has provisions that can stop pharmaceutical companies from charging prohibitive prices for life-saving drugs.

Section 3(d) states that “the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance” is not patentable. This prevents pharmaceutical “evergreening”; the practice of making minor modifications to existing drugs to obtain new patents without providing meaningful therapeutic benefits.

Pharmaceutical companies might otherwise patent new salt forms, polymorphs, or delivery methods of known drugs, extending monopolies on essentially the same medicine. Section 3(d) requires that such modifications demonstrate enhanced efficacy—typically meaning improved therapeutic effectiveness, not just better stability, easier manufacturing, or longer shelf life.

The landmark Novartis v. India case tested Section 3(d) when Novartis sought a patent for a beta crystalline form of Imatinib Mesylate, the active ingredient in its cancer drug Glivec. The Supreme Court upheld the rejection, finding that Novartis failed to demonstrate enhanced therapeutic efficacy compared to the known compound. This decision established that Section 3(d) serves as a significant bar against pharmaceutical evergreening.

Section 4 Atomic Energy Restrictions

Section 4 entitled ‘Inventions relating to atomic energy not patentable’ disallows any invention related to atomic energy according to the Atomic Energy Act 1962, which provides for the development, control, and use of atomic energy for the welfare of the Indian people and peaceful purposes.

This blanket exclusion removes all atomic energy inventions from the patent system, reflecting India’s strategic interests in nuclear technology and national security concerns. The Atomic Energy Act vests control of atomic energy research and applications in the government, precluding private patent monopolies in this field.

The prohibition covers inventions relating to nuclear reactors, atomic weapons, radioactive materials, and nuclear energy applications. Even peaceful uses of nuclear technology fall under this exclusion if they’re covered by the Atomic Energy Act. This policy ensures that nuclear technology development serves national interests rather than private commercial benefit.

Traditional Knowledge and Naturally Occurring Substances

India’s patent law specifically protects traditional knowledge from inappropriate patenting. Section 3 excludes inventions that merely use traditional knowledge or are based on naturally occurring substances without further inventive steps.

Naturally occurring substances, whether minerals, plants, animals, or microorganisms, cannot be patented simply because they’re discovered. If you discover a plant with medicinal properties, that discovery alone isn’t patentable. However, if you isolate and purify a compound from that plant, modify it chemically, or develop a specific therapeutic application with demonstrated technical advancement, those innovations may be patentable.

Traditional knowledge encompasses systems like Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, and Siddha that have existed in India for centuries. The Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) documents this knowledge to prevent foreign patent offices from granting patents on traditional knowledge mistakenly classified as novel inventions. This prevents “biopiracy”—situations where traditional knowledge is misappropriated through patents by foreign entities.

For inventors working with natural products or traditional medicine, the key to patentability is demonstrating significant technical advancement beyond what traditional knowledge teaches. Isolating active compounds, elucidating mechanisms of action, developing new formulations or delivery systems, or conducting rigorous clinical trials demonstrating efficacy may all constitute patentable advances built on traditional knowledge foundations.

How to Apply for a Patent?

Navigating India’s patent application process requires understanding prerequisites, online filing procedures, and examination timelines. I’ll walk you through each step so you can approach filing with confidence.

What Are the Prerequisites Before Filing a Patent Application?

Preparation before filing significantly impacts your application’s success. Skipping these prerequisites often leads to rejections, unnecessary expenses, or weak patents that competitors can easily circumvent.

Conduct Effective Prior Art Searches

Normally, you cannot get a patent if your invention has already been publicly disclosed prior to filing a patent application for your invention, so a search of all previous public disclosures should be conducted, including foreign patents and printed publications.

Prior art searching isn’t optional; it’s essential for evaluating patentability, avoiding wasted filing costs, and drafting strong claims that avoid known art. Comprehensive searches examine multiple databases, including patent databases, scientific literature, technical publications, and internet resources.

Professional Search Services vs. Self-Conducted Research

Registered patent attorneys or agents, or patent search firms, are often useful resources for conducting searches, and novices are encouraged to contact the nearest Patent and Trademark Resource Center for help from search experts in setting a search strategy.

Professional searchers bring expertise in database selection, query formulation, and result interpretation that significantly improve search quality. They understand patent classification systems, can search in multiple languages, and recognize relevant prior art that non-experts might miss. For high-value inventions or complex technologies, professional searches are worth the investment.

It is possible, though challenging, to conduct your own preliminary search. Self-conducted searches work best for inventors familiar with their technical field who understand patent searching basics.

Start with patent databases like the Indian Patent Office’s database. For global search, use databases like WIPO and the USPTO Patent Public Search tool. Don’t limit searches to patents. Academic databases, Google Scholar, industry publications, and technical forums often contain prior art. A single conference paper or thesis describing your invention can destroy novelty just as effectively as a patent.

Identifying Blocking Patents in Your Jurisdiction

Beyond patentability searching, identify existing patents that might block your invention’s commercialization. A blocking patent covers technology necessary to practice your invention, even if your invention is patentable as an improvement.

For example, if you develop a new smartphone feature but it requires using patented touchscreen technology, that touchscreen patent is blocking. You might obtain a patent on your feature, but you can’t sell phones using it without licensing the touchscreen patent from its owner.

Identifying blocking patents early enables strategic planning. You might design around blocked technology, negotiate licenses before investing in commercialization, or pursue cross-licensing arrangements where you trade your patent rights for access to blocking patents.

Types of Patent Searches: Patentability, Invalidity, and FTO

Different search types serve distinct purposes in your IP strategy:

Patentability searches evaluate whether your invention is novel and non-obvious before filing. These searches aim to find prior art most likely to be cited during examination, helping you assess filing prospects and draft claims that avoid known art. Conduct these searches before investing in patent applications.

Invalidity searches challenge existing patents’ validity, typically conducted by accused infringers defending against infringement allegations. These searches seek prior art not found during examination that demonstrates the patent should never have been granted. Invalidity searches are more exhaustive than patentability searches because they’re conducted after significant expenses have been incurred.

Freedom to operate (FTO) searches identify patents that might cover your planned products or activities. Unlike patentability searches focusing on your invention’s novelty, FTO searches examine whether practicing your invention infringes others’ patents. These searches should be conducted before launching products, even if you have your own patents, because your patents don’t grant freedom to operate, they only give you rights to exclude others.

Determining Patent Type: Provisional vs. Complete Specification

Based on your invention’s development stage and strategic goals, decide whether to file provisionally or directly with a complete specification.

File provisionally when:

- Your invention is conceptually developed, but implementation details need refinement

- You want to establish priority while continuing development

- Budget constraints make immediate complete filing impractical

- You need time for market testing before committing to full prosecution

- You want public disclosure rights while maintaining filing date security

File directly with a complete specification when:

- Your invention is fully developed with all implementation details worked out

- Competitive pressure requires immediate filing to beat potential rivals

- You need enforceable rights as quickly as possible

- The 12-month provisional period doesn’t provide sufficient strategic value

- You’re filing under PCT or claiming Paris Convention priority from foreign applications

Choosing Filing Route: Ordinary vs. PCT vs. Paris Convention

Your geographic protection needs determine the optimal filing route:

Ordinary national filing works when you need protection only in India. File directly with the Indian Patent Office without claiming foreign priority. This is the simplest and least expensive, but provides no international rights.

Paris Convention route suits situations where you’ve already filed in another Paris Convention country and want to claim that filing’s priority date. You have 12 months from your first filing to file in India while maintaining your original priority date. This route requires filing separate national applications in each country.

PCT route is optimal when you’re unsure which countries you’ll ultimately want protection in or when you need extended time to assess commercial potential before committing to expensive national phase filings. File an international application under PCT, receive an international search report, then enter the national phase in India and other countries within 30 months of your priority date.

Gathering Required Documents and Inventor Information

Before filing, compile:

- Complete description of the invention, including how it works and how to make it

- Drawings, diagrams, or flowcharts illustrating the invention

- Information about inventors’ names, addresses, and nationalities

- Priority documents if claiming Paris Convention or PCT priority

- Power of attorney if filing through a patent agent or attorney

- Proof of right to apply (assignment documents if the applicant isn’t the inventor)

For entities applying, gather company registration documents and authorization for the person signing on the entity’s behalf. For PCT applications entering the national phase in India, compile translations of foreign-language documents and the international search report.

How Do You File a Patent Application Online in India?

India’s patent system operates primarily through electronic filing, making the process accessible from anywhere with internet access.

Creating an Account on the Indian Patent Office Portal

Access the Indian Patent Office e-filing website and register for a new account. You’ll need a valid email address and mobile number for authentication. The system generates a user ID and password, enabling access to filing services.

Verify your account through the confirmation email sent by the system. Once verified, log in and complete your profile, including name, address, and contact information. This information populates your patent applications automatically, ensuring consistency across filings.

Step-by-Step E-Filing Process

After logging in, navigate to the “Patent” section and select “File Application.” Choose the application type from the options provided. It will also ask specification type, you will have two options to choose from: provisional and complete application.

You will also see other options such as no. of pages, no. of claims, no. of drawings, etc. Choose according to your application.

The system guides you through multiple screens, collecting:

Bibliographic information: Inventors’ names and addresses, applicant details, title of invention, technical field classification. Ensure all names are spelled correctly and addresses are complete—errors here can delay processing.

Specification upload: Upload your specification document (Word or PDF format) containing description, claims, abstract, and drawings. The Indian Patent Office provides formatting guidelines you must follow—non-compliant filings face objections.

Declaration and oath: The application includes declarations that you’re the true and first inventor, that the invention is new, and that you’ve disclosed all material prior art. Sign these declarations digitally or physically, depending on your filing method.

Fee calculation: The system calculates fees based on entity status (individual, startup, small entity, or large entity). Individuals and startups receive substantial fee reductions, making early filing more affordable.

Form 1, Form 2, Form 3, Form 5: When to Use Which Form

Indian patent applications use standardized forms for different purposes:

Form 1 is the main application form providing bibliographic data, inventor information, priority claims, and basic invention details. Every patent application requires Form 1.

Form 2 is the provisional or complete specification describing your invention in detail. For provisional applications, Form 2 contains a brief description. For complete applications, it includes a detailed description, claims, an abstract, and drawings meeting specific formatting requirements.

Form 3 is the statement and undertaking requiring disclosure of corresponding foreign applications. You must inform the Indian Patent Office about any applications for the same or substantially the same invention filed in other countries. This form is filed with the application and updated within six months of the examination request.

Form 5 is the declaration as to inventorship. It identifies who the true inventors are and confirms they’ve authorized the application. Joint inventors must all be listed.

Payment of Filing Fees: Categories and Amounts

Patent applications are subject to payment of basic filing fees, search fees, and examination fees, which are due when the application is filed, with additional excess claims fees or application size fees potentially due depending on claim numbers and specification length.

For example, filing a complete specification might cost (e-filing):

| S. No. | Description | Reduced Entities | Large Entities |

| 1 | Filing application for grant of patent (up to 30 pages, 10 claims, 1 priority) | 1600/- | 8000/- |

Fees vary depending on the type of patent application submitted and qualification for fee discounts. Check the current fee schedule before filing, as rates are periodically updated.

Acknowledgment Receipt and Application Number Assignment

Upon successful filing, the system generates an acknowledgment receipt with your application number.

The filing date is typically the date the Indian Patent Office receives all required documents and fees. If your application is incomplete, the Office sends a Notice of Incomplete Application giving you time to submit missing items with a possible surcharge, and the filing date becomes the date corrections are made.

For provisional applications, your filing date establishes priority. You have 12 months from this date to file the complete specification. For complete applications, your filing date begins the 20-year patent term and establishes prior art cutoff dates.

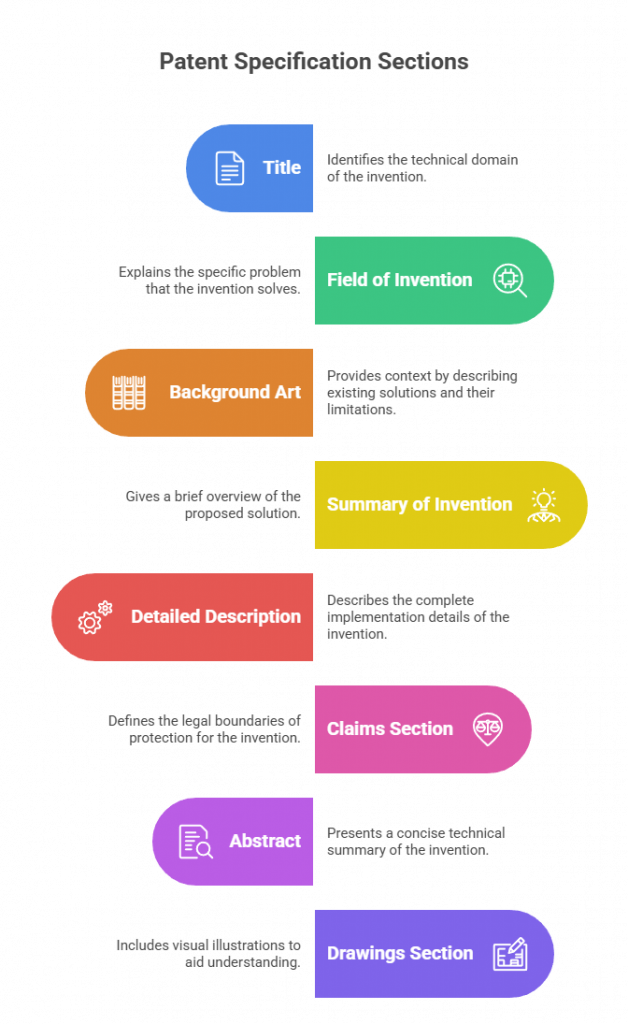

What Are the Essential Components of a Complete Patent Specification?

A complete specification is the legal document defining your patent’s scope and teaching how to practice your invention. Getting this right is crucial because you cannot later broaden patent scope, only narrow it through amendments.

Title, Field of Invention, and Background Art

A complete specification must include a title that is clear, concise, and relevant, define the technical domain through the field of invention, and explain the problem or gap the invention addresses through background art.

Title: The title should accurately describe your invention in 15 words or fewer. Avoid overly broad titles like “Improved Device” or overly narrow titles that limit your invention’s scope. “Wireless Charging System for Electric Vehicles” is specific yet broad enough to cover various implementations.

Filed of Invention: The field of invention section identifies the technical area your invention belongs to. This helps patent offices assign applications to examiners with appropriate expertise and helps future searchers find your patent. State the technical field concretely: “This invention relates to lithium-ion battery thermal management systems for electric vehicles.”

Background Art: Background art explains the state of technology before your invention, identifying problems your invention solves. Cite relevant patents and publications showing what existed previously. This section helps demonstrate why your invention represents an advance over prior art, but be careful not to praise prior art too highly—doing so can make proving non-obviousness more difficult.

Summary & Detailed Description and Best Mode Disclosure

The summary provides an overview of how the invention solves the identified problem, while the detailed description explains every element, including methods, processes, and working mechanisms.

Summary: The summary briefly outlines your invention’s key features and advantages without excessive detail. Think of it as an elevator pitch for your invention, giving readers enough information to understand what you’ve invented and why it matters.

Detailed Description: The detailed description forms your specification’s heart. It must completely describe a specific embodiment of the process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or improvement invented, and must explain the best mode of carrying out the invention. “Best mode” requires disclosing the best way you know to practice your invention at filing—you cannot withhold superior techniques or optimal conditions.

Write the description so someone skilled in your field could reproduce your invention without undue experimentation. Include:

- Structural descriptions with reference to drawings

- Operating principles explaining how your invention works

- Manufacturing methods or synthesis routes

- Specific examples implementing your invention

- Alternative embodiments showing variations within your invention’s scope

- Comparative examples demonstrating advantages over prior art

For chemical inventions, provide synthesis routes, starting materials, reaction conditions, and purification methods. For software inventions, describe algorithms, data structures, flowcharts, and implementation logic. For mechanical inventions, explain component relationships, assembly methods, and operational sequences.

Claims Drafting: Independent vs. Dependent Claims

Claims particularly point out and distinctly claim the subject matter regarded as the invention, defining the scope of patent protection and determining questions of infringement. Claims are the legal boundaries of your patent, they define exactly what’s protected and what’s not.

Independent claims stand alone, containing all elements necessary to define your invention. They establish the broadest protection scope you’re claiming. Independent claims typically begin “A device comprising…” or “A method comprising…” and list essential elements.

Draft independent claims broadly enough to cover variations competitors might use to design around your patent, but not so broadly that they read on prior art. This balance is critical—overly broad claims get rejected during examination, while overly narrow claims provide weak protection easily circumvented.

Dependent claims refer back to independent claims, adding additional limitations that narrow the scope. They provide fallback positions if independent claims are rejected or invalidated. Dependent claims might specify:

- Particular materials, dimensions, or parameters

- Specific implementations or embodiments

- Preferred variations or combinations of elements

- Optional features improving performance

A typical claim structure includes one independent claim followed by several dependent claims:

Claim 1 (independent): A battery thermal management system comprising: [list essential elements]

Claim 2 (dependent): The system of claim 1, wherein the cooling channels are configured in a serpentine pattern.

Claim 3 (dependent): The system of claim 1, wherein the coolant is a water-glycol mixture.

Dependent claims are cheaper to file than additional independent claims and provide strategic advantages during examination—examiners must consider each claim separately, and dependent claims often survive even if independent claims are rejected.

Abstract and Drawing Requirements

The abstract provides a brief technical summary of your invention, typically 150 words or fewer. It helps searchers quickly determine whether your patent is relevant to their search without reading the entire specification. Abstracts appear on the patent’s face and in patent databases.

Drawings must conform to patent office drafting guidelines, be labeled clearly, and provide enough detail for readers to understand the invention’s design and use. Almost all patent applications benefit from drawings illustrating the invention’s structure and operation.

Drawing requirements include:

- Black and white line drawings (no color unless absolutely necessary)

- Clear, legible lines and text

- Reference numerals identifying each element

- Multiple views showing different perspectives

- Exploded views for assembled devices

- Flowcharts for methods or processes

- Schematic diagrams for electrical or software inventions

The patent office selects one representative drawing to appear on the patent’s face. Choose your most important or distinctive view when creating drawings.

For software inventions, flowcharts, system architecture diagrams, and user interface screenshots serve as drawings. For chemical inventions, molecular structures, reaction schemes, and apparatus drawings illustrate synthesis methods. For mechanical inventions, assembly drawings, cross-sections, and detail views show structure and operation.

How Does the Patent Examination Process Work in India?

Understanding examination timelines and procedures helps you navigate the patent process strategically and respond effectively to patent office actions.

18-Month Publication Timeline

Patent applications are published in the Official Patent Journal after 18 months from the filing date (or priority date if claimed), making them accessible for public review. Publication occurs automatically unless you file an early publication request or the application is withdrawn or abandoned before 18 months.

Publication serves several purposes. It discloses your invention publicly, establishing prior art that can be cited against later applications claiming the same invention. It also notifies competitors of your patent application, potentially deterring them from investing in similar technologies or enabling them to prepare opposition or design-around strategies.

After publication, you gain provisional rights, meaning that once the patent grants, you can claim damages for infringement occurring after publication. However, these rights are provisional—if your application is ultimately rejected or abandoned, publication provides no enforceable rights.

31-Month Examination Request Deadline

A request for examination may be made within 31 months from the priority date. Filing an application doesn’t automatically trigger examination; you must file a separate examination request (Form 18) and pay examination fees.

Expedited examination is available in certain cases as per Rule 24C of the Patent Rules. Expedited examination significantly reduces time to grant, sometimes receiving first office actions within months rather than years.

Consider requesting expedited examination when:

- You need to obtain patents quickly for licensing or enforcement

- Competitors are infringing, and you need enforceable rights

- Investors require granted patents as milestones

- Your technology is rapidly evolving and delay risks obsolescence

Office Action Responses and Claim Amendments

Upon issue of the first examination report, an applicant is granted a period of six months (extendable by up to 3 more months) to address objections raised in the office action from the date of its issue.

Office actions (called First Examination Reports in India) identify rejections, objections, or deficiencies in your application. Common issues include:

- Prior art-based rejections citing patents or publications rendering claims unpatentable

- Lack of clarity in claims or insufficient disclosure

- Patentability objections under Sections 3 or 4

- Formal deficiencies like missing documents or incorrect formats

Respond to each objection specifically and thoroughly. If the examiner cited prior art, explain why your claims are patentable over that art, identify differences, demonstrate non-obviousness, or amend claims to overcome the prior art. If objections concern clarity or disclosure, amend the specification or claims to address the deficiency.

Claim amendments are common during prosecution. You can narrow claims to overcome prior art, clarify ambiguous language, or correct errors. However, you cannot broaden claims beyond what your original specification disclosed, amendments can only narrow or clarify, never expand.

Strategic amendment practices include:

- Amend independent claims to incorporate features from dependent claims

- Add new dependent claims capturing alternative embodiments

- Clarify functional language with structural limitations

- Remove elements found in prior art while retaining novel features

Support amendments with arguments explaining why the amended claims are patentable. Reference specific disclosure passages supporting amendments, cite legal precedents when appropriate, and distinguish prior art clearly. Well-crafted responses can overcome most objections without requiring multiple examination rounds.

If the examiner maintains rejections after your response, you may request a hearing to present arguments orally. This provides an opportunity to clarify misunderstandings, present technical explanations, or negotiate acceptable claim language. Examiners often prove more flexible in hearings than in written correspondence.

Pre-Grant, Post-Grant Opposition Proceedings and Revocation Proceedings

The Patent Act provides mechanisms for third parties to challenge patent applications before grant (pre-grant opposition) and after grant (post-grant opposition and revocation).

Pre-grant opposition allows any person to file opposition after publication but before grant. Oppositions typically cite prior art not found during examination, challenge patentability under Sections 3 or 4, or argue that the invention was publicly known in India. The patent office considers opposition submissions when examining the application, though the opponent has limited participation rights.

Pre-grant opposition provides a lower-cost mechanism for competitors to block patents than post-grant proceedings. If you’re monitoring competitor applications in your field, consider filing pre-grant oppositions citing prior art that the examiner might have missed. This can prevent problematic patents from issuing.

Post-grant opposition can be filed within 12 months of patent grant by any interested person. Grounds include prior publication, obviousness, insufficiency of disclosure, non-patentability under Sections 3 or 4, or that the patent was wrongfully obtained. Post-grant opposition proceedings are more formal than pre-grant, involving an Opposition Board that examines evidence and conducts hearings.

An Opposition Board is constituted to examine post-grant oppositions and submit recommendations to the Controller, who makes the final decision. The process can take years and involves substantial costs for both parties. However, it provides a complete record that can influence subsequent litigation if the patent survives opposition.

Revocation proceedings can be filed in court or with the patent office at any time during the patent’s life. Courts handle revocation petitions in conjunction with infringement suits; defendants often counterclaim for revocation when sued for infringement. Appeals against Controller decisions are filed before the respective High Courts, and revocation petitions are also filed before the High Courts.

Grounds for revocation mirror post-grant opposition grounds but include additional bases like non-working of the invention in India for certain patent categories, or that the patent was obtained through fraud or misrepresentation. Revocation provides a mechanism to eliminate invalid patents blocking your freedom to operate.

Patent Rights and Enforcement Mechanisms

Once you obtain a patent, understanding the exclusive rights it grants and how to enforce them becomes critical for extracting value from your intellectual property investment.

What Exclusive Rights Do Patent Holders Possess?

Patent ownership conveys powerful legal rights that form the foundation of your competitive advantage and licensing opportunities.

Section 48 Rights Analysis: Making, Using, Selling, Importing

According to Section 48, patent law confers exclusive rights to the patentee to prevent third parties who do not have consent from making, using, offering for sale, selling or importing the patented product in India. These rights represent the core monopoly a patent grants.

Breaking down each exclusive right:

Making: You can prevent anyone from manufacturing your patented invention in India without permission. This covers complete manufacture as well as substantial manufacture; if someone makes critical components but assembles the final product elsewhere, they may still infringe your patent.

Using: You can stop unauthorized use of your patented invention. This is particularly important for process patents—even if someone manufactures a product using your patented process outside India, using that product in India may constitute infringement if it’s the direct product of your patented process.

Offering for sale: Merely advertising or offering to sell infringing products constitutes infringement, even if no actual sale occurs. This allows you to take action against potential infringers before they actually enter the market, preventing market disruption.

Selling: Actual sales of infringing products clearly constitute infringement. Each sale represents a separate infringing act, potentially increasing damages calculations based on the volume of infringing sales.

Importing: You can block the importation of infringing products into India. This is crucial because it allows you to prevent foreign manufacturers who don’t respect your Indian patent from supplying the Indian market. Customs enforcement can intercept infringing imports at the border.

For process patents, patent holders can prevent third parties from using the process and from using, offering for sale, selling, or importing products obtained directly by that patented process in India. This extended protection for process patents recognizes that processes are often harder to detect and prove than product patents.

Territorial Limitations and Enforcement Boundaries

Patents are effective only within the country and its territories and possessions, and the same territorial limitation applies to Indian patents. Your Indian patent grants rights only within India; it provides no protection in other countries.

This territorial nature of patents requires strategic filing decisions. If you manufacture in China, sell in Europe, and have research facilities in the United States, you need patents in all three jurisdictions to prevent competitors from exploiting your invention in those markets. A single patent in one country leaves your invention unprotected everywhere else.

Territorial limitations also affect enforcement. You can only sue for infringement occurring in India under your Indian patent.

The territorial nature of patents explains why multinational companies often file patent families covering the same invention in dozens of countries. While expensive, comprehensive geographic coverage prevents competitors from manufacturing in one country while selling in others, maintaining market exclusivity globally.

20-Year Term Calculation and Maintenance Requirements

Utility and plant patents have a term for up to 20 years from the date the first non-provisional application for patent was filed, and in India, the term of every patent is 20 years from the date of filing the patent application, irrespective of whether it is filed with a provisional or complete specification.

The 20-year term begins from your earliest filing date. If you filed provisionally first, the 20-year term runs from that provisional filing date, not from when you filed the complete specification.

You will need to pay maintenance fees on a certain schedule after the utility patent is issued to keep it in force. In India, renewal fees are due annually after the third year following the patent grant. Missing renewal fee deadlines results in your patent lapsing, though the Patent Act provides limited restoration opportunities if you act quickly after realizing the lapse.

How Is Patent Infringement Determined and Proven?

Establishing infringement requires a systematic analysis comparing the accused product or process against your patent claims. Understanding infringement principles helps you enforce your rights and avoid infringing others’ patents.

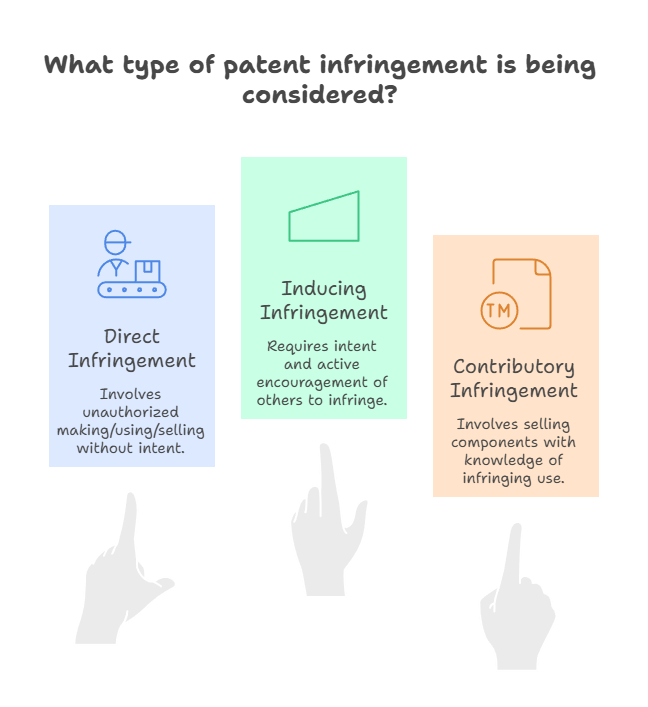

Direct vs. Indirect Infringement Standards

Direct infringement is the straightforward case; someone makes, uses, sells, offers for sale, or imports your patented invention without permission. You need only prove that the accused product or process falls within your claim scope. No intent to infringe is required; even innocent infringement, where the infringer didn’t know about your patent, constitutes direct infringement.

To establish direct infringement, you must prove:

- You own a valid, enforceable patent

- The accused product or process falls within the scope of at least one patent claim

- The infringement occurred within India during your patent’s term

Each element is essential. If your patent is invalid, even proven use doesn’t constitute actionable infringement. If the accused product lacks even one claim element, there’s no literal infringement regardless of similarities. If the activity occurred outside India or after your patent expired, you have no recourse.

Indirect infringement (also called contributory infringement) involves inducing others to infringe or selling components specifically designed for infringing use. While direct infringement is well-established in Indian law, indirect infringement principles are less developed than in jurisdictions like the United States.

Contributory infringement involves selling components or materials specifically adapted for infringing use with limited non-infringing applications. Inducing infringement occurs when you actively encourage or instruct others to infringe patents. Selling kits with instructions for assembly into infringing devices, or providing services facilitating patent infringement, may constitute inducement. However, you must have knowledge of the patent and specifically intend to cause infringement.

Literal Infringement vs. Doctrine of Equivalents

Literal infringement exists when the accused product or process contains every element recited in a patent claim, as literally claimed. Claim analysis is systematic: identify each claim element, then determine whether the accused product includes each element exactly as claimed.

For example, if your claim recites “A device comprising: element A, element B, and element C,” the accused device must include A, B, and C for literal infringement. If it contains A and B but not C, there’s no literal infringement of that claim, regardless of how similar it is overall.

The Doctrine of Equivalents addresses situations where an accused product doesn’t literally infringe but performs substantially the same function in substantially the same way to achieve substantially the same result. This doctrine prevents accused infringers from avoiding liability through insubstantial changes that don’t alter the invention’s fundamental nature.

The doctrine of equivalents applies when someone substitutes an equivalent element for a claim element. For example, if your claim requires “a steel shaft” and the accused device uses a titanium shaft performing the same function identically, the doctrine of equivalents may establish infringement even though “titanium” isn’t literally “steel.”

Applying the doctrine requires asking: Does the substitute element perform substantially the same function, in substantially the same way, to achieve substantially the same result as the claimed element? If yes, infringement under the doctrine of equivalents may be found. Additionally, courts consider whether the substitute would have been obvious to a person skilled in the art when the accused infringement began.

Burden of Proof Requirements in Litigation

Section 104A of the Patents Act deals with the burden of proof in patent infringement proceedings, specifying the evidence required to establish infringement. Generally, the patent holder bears the burden of proving infringement occurred.

For product patents, you must prove that the accused product falls within your claim scope. This often requires obtaining samples of the accused product, conducting analysis to understand its structure and operation, and preparing detailed claim charts comparing each claim element to corresponding features in the accused product.

For process patents, proving infringement is more challenging because processes occur inside manufacturing facilities you can’t access. To address this, Section 104A provides that in process patent cases where the patented process produces a new product, courts may presume the same product made by someone else was made using the patented process. The burden then shifts to the accused infringer to prove they used a different, non-infringing process.

This burden-shifting is crucial for process patent enforcement. Without it, proving process infringement would be nearly impossible since you’d need to access competitors’ confidential manufacturing facilities. The presumption gives process patents teeth while allowing accused infringers to rebut the presumption by demonstrating their alternative processes.