Master US small business bookkeeping from India: Complete guide from entity setup to financial statements. Learn QuickBooks, client acquisition strategies, and earn $15-50/hour remotely. Start today!

Table of Contents

While you’re competing for ₹30,000/month jobs in India, US small businesses are desperately searching for reliable bookkeepers who can manage their finances remotely. And they’re willing to pay $15-50 per hour for someone with the right skills.

I’ve seen so many Indian commerce graduates, CA students, and working accountants transform their careers by mastering US small business bookkeeping that it is a wonder not everybody is looking into it. The difference between earning ₹30,000 working for an Indian CA firm and earning $2,000-$5,000 serving US clients from India isn’t just in the outsized financial gains but also the experience you gain and the skills you acquire with international clients.

What this guide covers: Your complete setup-to-financial statements roadmap

This isn’t another generic bookkeeping tutorial written for American business owners. This is your comprehensive roadmap for understanding US entity types, bookkeeping practices, and everyday work to deliver professional financial statements that US clients will actually pay for.

I’ll walk you through every phase: setting up a new US small business in accounting software, recording daily transactions the American way, executing monthly close procedures that separate beginners from professionals, and preparing the three critical financial statements that prove business health.

Who this is for: Indian commerce grads, Tally users, aspiring remote bookkeepers

If you’re a BCom or MCom graduate looking for your first high-paying remote opportunity, this guide is for you. If you’re a working accountant tired of Indian salary limitations and ready to access US market rates, you’re in the right place. If you’re a CA or CS professional wanting to diversify your income during articleship or practice-building years, keep reading.

Maybe you’ve mastered Tally for Indian businesses but feel intimidated by QuickBooks and US GAAP. You may understand debits and credits, but aren’t sure how US entity types affect bookkeeping methods. Or you might have the technical skills, but you want to find out how to bridge the work culture gap. If you have doubts about working for American businesses as a remote bookkeeper, this guide is for you.

Why US bookkeeping is different (and why that’s good news for you)

Many Indian accounting professionals underestimate how different US small-business bookkeeping can be. US firms commonly run as LLCs, S or C corporations, and report under US GAAP when they prepare formal financials, though smaller businesses often keep tax- or cash-basis books for simplicity. US small businesses overwhelmingly use platforms like QuickBooks or Xero rather than Tally.

These differences are not automatically easier or harder. They’re different. The practical upside is that learning US rules, software, and compliance creates a specialist skill set that clients value. That opens higher-paying remote-work opportunities if you position yourself right. Note: typical US staff/bookkeeper pay averages in the low-to-mid $20s per hour, while experienced freelance specialists or fractional controllers can command higher rates. Use that spread to offer US-standard quality at competitive, India-based rates.

What you’ll learn: Technical skills + compliance + career strategy

This guide delivers three layers you won’t find in typical bookkeeping tutorials. First, the technical foundation: entity types, chart of accounts setup, transaction recording, reconciliation procedures, and financial statement preparation. This matches what competitors teach, but I’ll show you through the lens of serving US clients remotely from India.

Second, the compliance and standards bridge: how US bookkeeping differs from Indian practices, what legal requirements apply when you work for American clients, and how to navigate W-8BEN forms and cross-border payment issues. This is the confidence-building layer that helps you transition from Tally-based Indian accounting to QuickBooks-based US systems.

Third, the culture fit strategy, which will help you fit in by knowing the invisible-to-the-beginners US small business practices that will make you irresistible to thje market.

By the end of this guide, you’ll have a complete roadmap from learning fundamentals to landing your first US client to building a sustainable remote bookkeeping practice earning $2,000-5,000 monthly.

Phase 1: How to Set Up US Bookkeeping for a New Small Business

What Are the US Small Business Entity Types and Their Bookkeeping Requirements?

Understanding US business entity types is your foundation for everything else. Unlike India, where most small businesses are sole proprietorships or private limited companies, the US has a more varied landscape. What matters to you as a remote bookkeeper is that each entity type comes with different bookkeeping complexity, compliance requirements, and therefore different rates you can charge.

Sole Proprietorship vs LLC vs S-Corp vs C-Corp

Let’s start with what you’ll encounter most often: Sole Proprietorships. This is the simplest US business structure. It’s a one-person business where the owner and business are legally the same entity. Think of it like a proprietorship firm in India. The owner reports business income and expenses on their personal tax return using Schedule C.

For bookkeeping purposes, sole proprietorships are straightforward. You’ll maintain separate books for the business, but there’s no separate tax return. Most sole proprietors use cash basis accounting (recording income when received and expenses when paid). You’ll typically use QuickBooks Online Simple Start or even a spreadsheet for very small operations.

Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) An LLC gives owners limited liability protection. Personal assets are generally separate from business liabilities, so LLC plays a similar role to a Private Limited Company in India, but with fewer formalities and more tax flexibility. By default, a single-member LLC is a “disregarded entity” (taxed like a sole proprietor) and a multi-member LLC is taxed like a partnership. However, an LLC can elect corporate tax status (C-corp via Form 8832 or S-corp via Form 2553) if that suits the owners.

That election changes everything for bookkeeping. Ask every LLC client, “How is your LLC taxed?” A single-member LLC reported on Schedule C typically requires straightforward books. An LLC taxed as an S-corp needs payroll set up, employer filings (quarterly Form 941 and related state returns), reasonable-salary calculations, and tighter payroll and tax tracking. In short: entity class + tax election = your bookkeeping playbook.

S-Corporations aren’t separate legal entities. It’s a tax status that an LLC or Corporation can elect by filing IRS Form 2553. Once elected, the company’s profits “pass through” to its shareholders, avoiding double taxation.

The catch? Any owner who works in the business must take a reasonable salary through payroll, with all required withholdings and quarterly payroll tax filings (Form 941, state equivalents). You’ll need to understand US payroll cycles, reconcile payroll accounts, and ensure deposits are made on time.

S-Corps file a separate annual return (Form 1120-S) and issue Schedule K-1s to shareholders. Because the IRS closely reviews officer-compensation and distribution accuracy, the books must stay clean: separate business accounts, correctly classified distributions, and monthly reconciliations.

In short, S-Corp bookkeeping demands payroll knowledge and strict separation of funds, work that reasonably bills at $25–40/hour versus the entry-level $15–20/hour for sole-proprietor setups.

C-Corporations are the most complex entity type but are rare among small businesses. C-Corps are taxed separately from their owners (double taxation, which is once at the corporate level and once when distributed to shareholders). You’ll encounter C-Corps mainly with venture-backed startups or larger small businesses with significant outside investment.

For C-Corps, bookkeeping must be impeccable. You’ll need full accrual accounting, detailed equity tracking, proper corporate minutes, and quarterly financial statements. Unless you’re an experienced bookkeeper, I’d recommend starting with sole proprietorships and LLCs before taking on C-Corp clients.

How Business Entity Type Influences US Bookkeeping Methods and Tax Reporting

Here’s the practical reality: entity type determines how complex your bookkeeping needs to be, which software features you’ll use, and how much you should charge. Let me break down the connections you need to understand.

Sole proprietorships and single-member LLCs generally use cash basis accounting unless they exceed $25 million in annual revenue. Their bookkeeping flows directly into Schedule C of the owner’s personal Form 1040 tax return. You’ll categorize income and expenses (advertising, vehicle, utilities, supplies, etc.) and calculate net profit or loss. No separate business tax return needed. This is the best entry point for beginners, simple enough to master within two to three months of focused learning.

Multi-member LLCs taxed as partnerships require Form 1065 (Partnership Return) and Schedule K-1s for each partner showing their share of income, deductions, and credits. Your bookkeeping must accurately track each partner’s capital account, contributions, distributions, and profit/loss allocation. This is moderately complex. Expect 6-12 months of experience before you’re comfortable handling partnership bookkeeping independently.

S-Corporations (whether LLC or Corp structure) need Form 1120-S annual returns plus payroll compliance. You’ll track shareholder basis (initial investment plus/minus profit/loss plus/minus distributions). S-Corps must differentiate between salary paid to owner-employees (subject to payroll tax) and distributions (not subject to payroll tax). The IRS watches this closely to prevent owners from avoiding payroll taxes by taking everything as distributions.

C-Corporations file Form 1120 and pay a flat 21% federal corporate tax. Their bookkeeping involves tracking common and preferred stock, additional paid-in capital, and retained earnings, often across multiple share classes. While quarterly financial statements aren’t legally required for private C-Corps, they’re standard practice for investor transparency. Because of their complexity and regulatory depth, C-Corp bookkeeping is best handled by professionals with at least a couple of years of solid accounting experience.

According to IRS Statistics of Income (Tax Year 2022), Schedule C/sole-proprietor filings totaled about 31.0 million returns, while partnerships (including many multi-member LLCs) filed roughly 4.5 million returns, and corporate returns totaled about 6.8 million. That math implies roughly 70–75% of business tax filings are Schedule C sole proprietorships, with partnerships and corporations making up the bulk of the rest. Practically speaking, that’s why your first priority should be bookkeeping for sole proprietorships and simple LLCs. They represent the largest volume of small businesses you’ll encounter, but don’t assume they account for the bulk of commercial opportunity. The dollar value and frequency of paid work also depend on firm size and complexity.

What remote US bookkeepers need to know about each structure

As an Indian professional serving US clients remotely, you need to position yourself strategically. Here’s my advice based on what actually works in the market.

Start with sole proprietorships and single-member LLCs. Target service-based businesses (consultants, freelancers, coaches, and online businesses) that don’t carry inventory. These clients need basic transaction categorization, monthly reconciliation, quarterly P&L statements, and annual tax prep handoff to their CPA. You can charge $15-20/hour or $300-500/month for this level of service once you’re competent.

Progress to S-Corps and multi-member LLCs after 6–12 months of handling sole proprietorships and single-member LLCs. These clients need more advanced bookkeeping: payroll setup, quarterly tax filings (Form 941 and Form 940), and detailed financial reporting. You’ll also coordinate with the client’s payroll service to ensure accuracy.

You can typically make $25–35/hour or $600–1,200/month, though rates vary depending on client size, complexity, and your experience. Mastering this level positions you for higher-value, more consistent US bookkeeping work.

Avoid C-Corps initially unless you have 2+ years of experience or CPA-level credentials. The liability risk is higher, expectations are more demanding, and you’re competing with experienced US bookkeepers. Build your skills and reputation with simpler entity types first.

Here’s the positioning that works: “I specialize in bookkeeping for US sole proprietorships, LLCs, and S-Corporations in [specific industry like e-commerce, consulting, or real estate]. I handle daily transaction entry, monthly reconciliation, and financial statement preparation using QuickBooks Online. I coordinate with your CPA for tax season and ensure your books are audit-ready year-round.”

Notice what this does: you’re specific about entity types you serve (excluding C-Corps), you mention industry specialization (building expertise in one vertical), you clarify exactly what you do and don’t do (bookkeeping, not tax filing), and you position yourself as part of the client’s professional team (working with their CPA).

What Essential Startup Documents are needed for a US Small Business Bookkeeping Setup

Before you can start bookkeeping for a US small business client, certain foundational documents and accounts must be in place. Think of this as the pre-flight checklist. Skip any item and your bookkeeping will have problems from day one.

What is EIN (Employer Identification Number) and why it matters

The Employer Identification Number (EIN) is essentially a business’s Social Security number. It’s a nine-digit identifier issued by the IRS. Every business entity except sole proprietorships without employees must have an EIN. Even sole proprietorships often get EINs to avoid using the owner’s Social Security number for business purposes.

As a remote bookkeeper, you need to understand why the EIN matters to you. First, you’ll need the EIN to set up the business in QuickBooks or Xero. The software asks for it during company file creation. Second, the EIN appears on all tax forms, payroll documents, and official correspondence. Third, clients sometimes ask you to verify their EIN or help them retrieve it if lost.

The IRS issues EINs free of charge through their online application, phone line, or mail. Most US businesses obtain their EIN online within minutes. If your client doesn’t have an EIN yet, you can guide them through the application process, though technically you cannot apply for an EIN on behalf of a client (the business owner must submit the application).

When you start working with a new client, add “Verify EIN” to your onboarding checklist. You’ll need it for software setup, and missing or incorrect EINs cause problems with tax filings later. Store the EIN securely in your client files. It’s sensitive information that should be protected like a password.

Business bank account setup and separation from personal finances

Here’s a non-negotiable rule in US small business bookkeeping: business and personal finances must be completely separated. This means a dedicated business checking account (and often a business savings and business credit card) that’s used exclusively for business transactions.

Why does this separation matter so much? Legally, it protects the business owner’s limited liability status. If you’re mixing personal and business expenses, the IRS or courts can “pierce the corporate veil” and hold the owner personally liable for business debts. For bookkeeping purposes, separation makes your job 100 times easier. You’re not sorting through personal grocery purchases and kids’ school fees to find business transactions.

When you’re onboarding a new US small business client, verify they have separate business accounts. If they’re still using personal accounts for business, that’s your first recommendation: “Before we begin bookkeeping, you need to open a dedicated business checking account. This is required for proper bookkeeping and liability protection.”

Most US banks offer business checking accounts through institutions like Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, or online banks like Novo and Mercury. Account opening requires the business’s legal documents (Articles of Organization for LLC, EIN letter, etc.). Your role isn’t to open accounts for clients but to ensure they have proper accounts before you start recording transactions.

Here’s a practical tip: when connecting bank accounts to QuickBooks Online or Xero, you’ll use the bank feed feature that automatically imports transactions. This automated import is what makes modern bookkeeping efficient. But it only works if the client has business accounts with participating banks. Chase, Bank of America, and other major US banks all support bank feeds. International banks generally don’t.

Cash vs. Accrual Accounting: Choosing the Right Method for U.S. Small Businesses

This is one of the most important decisions in the US bookkeeping setup, and it’s different from how most Indian small businesses operate. Let me break down both methods and help you understand when to use each.

Cash basis accounting records income when cash is received and expenses when cash is paid. If you invoice a client on January 25th but they pay on February 10th, cash basis records the income in February. If you receive a bill on March 20th but pay it April 5th, the expense goes on April’s books. This matches your actual bank account activity.

Accrual basis accounting records income when earned (when you send the invoice) and expenses when incurred (when you receive the bill), regardless of cash movement. Same example: invoice sent January 25th is recorded as January income, even if payment comes in February. Bill received March 20th is March expense, even if paid in April.

According to US GAAP principles maintained by FASB, accrual accounting provides a more accurate picture of business performance because it matches revenues with related expenses in the same period. However, the IRS allows small businesses (under $25 million annual revenue) to use cash basis for tax purposes.

Here’s my practical guidance for choosing methods: Cash basis works best for service businesses without inventory, businesses with simple operations, very small businesses (under $100,000 annual revenue), and businesses where the owner manages bookkeeping themselves. The advantage: simplicity. Cash basis is intuitive. It matches bank statements directly. The disadvantage: it doesn’t show true profitability when you have timing differences between invoices and payments.

Accrual basis works best for businesses with inventory (required by IRS), businesses seeking loans or investors (banks want accrual financials), growing businesses that need accurate performance tracking, and businesses with significant accounts receivable or payable. The advantage is accurate profit tracking. The disadvantage is more complex bookkeeping requiring adjusting entries.

As a remote bookkeeper serving US small businesses, you’ll work with both methods. My recommendation: become proficient in cash basis first (simpler to learn), then add accrual basis skills after 3-6 months. When discussing method choice with new clients, ask about their industry, revenue level, and whether they’re seeking financing. Default to accrual for any business with inventory or revenues above $500,000.

Single-Entry vs Double-Entry Bookkeeping: Which Method Suits Your U.S. Small Business Client?

If you’re coming from a Tally or accounting background in India, you already understand double-entry bookkeeping. It’s the foundation of proper accounting worldwide. But you’ll encounter some very small US businesses still using single-entry systems, so you need to understand both and know when to recommend an upgrade.

Single-entry bookkeeping is like maintaining a checkbook register. You record each transaction once, noting date, description, and amount. Income increases your balance, expenses decrease it. That’s it. No debits and credits, no balanced accounts, no trial balance. Single-entry works only for very small, cash-basis businesses without inventory, employees, or complex transactions.

In my experience, single-entry is appropriate for freelancers and solopreneurs with under $50,000 annual revenue, all-cash operations, and no plans to seek financing or sell the business. Think: independent consultant, sole proprietor photographer, small coach or trainer. Even then, I recommend they transition to double-entry as revenue grows.

Double-entry bookkeeping is what you know from your accounting education: every transaction affects at least two accounts, with debits equaling credits. When a business sells a service on credit, you debit Accounts Receivable and credit Service Revenue. When they receive payment, you debit Cash and credit Accounts Receivable. This self-checking system ensures accuracy and provides complete financial information.

According to QuickBooks accounting principles, double-entry is required for accrual accounting, is necessary for producing proper financial statements (balance sheet, P&L, cash flow), catches errors automatically (when debits don’t equal credits, you know there’s a mistake), and is expected by CPAs, lenders, and investors.

Here’s the good news: QuickBooks Online and Xero use double-entry by default. Even if your client doesn’t understand debits and credits, the software handles it in the background. When you enter an invoice, QuickBooks automatically creates the double-entry (DR: Accounts Receivable, CR: Income). When you record a payment, it creates the entry (DR: Cash, CR: Accounts Receivable).

Your role as a bookkeeper is to ensure transactions are categorized correctly. The software handles the double-entry mechanics. However, understanding what’s happening behind the scenes is crucial when you need to create journal entries, investigate discrepancies, or explain reports to clients.

My recommendation: Always use double-entry bookkeeping for US small business clients, even very small ones. Modern software makes it as easy as single-entry while providing far superior financial information. The only exception is if a client absolutely insists on spreadsheet bookkeeping and refuses software, single-entry might be their only option. But I’d encourage them to reconsider.

How to Set Up the Chart of Accounts

The Chart of Accounts (COA) is your bookkeeping foundation. It’s the organizational framework for every financial transaction. Think of it as the filing system for your client’s financial data. Get this right at setup, and bookkeeping flows smoothly. Set it up poorly, and you’ll spend months correcting miscategorizations.

What is a Chart of Accounts and why it’s your foundation for US remote bookkeeping

The Chart of Accounts is a categorized list of all accounts used to organize financial transactions. Every transaction you record gets assigned to one or more accounts from the COA. When you purchase office supplies, it goes to “Office Supplies Expense.” When you receive payment from a customer, it hits “Cash” and reduces “Accounts Receivable.”

The COA follows the accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity, with Revenue and Expenses feeding into Equity through Retained Earnings. Let me break down each type:

Assets are things the business owns or is owed. This includes Cash (checking account, savings account, petty cash), Accounts Receivable (customer IOUs), Inventory (for product businesses), Prepaid Expenses (insurance paid in advance, prepaid rent), Fixed Assets (equipment, vehicles, computers), and Accumulated Depreciation (contra-account reducing fixed asset value over time).

Liabilities are what the business owes to others. This includes Accounts Payable (vendor bills not yet paid), Credit Cards (business credit card balances), Loans (bank loans, vehicle loans, lines of credit), Accrued Expenses (expenses incurred but not yet billed like wages payable), and Sales Tax Payable (sales tax collected from customers but not yet remitted to state).

Equity represents the owner’s stake in the business. For sole proprietorships and LLCs, this includes Owner’s Equity (initial investment), Owner’s Draw (money taken out by owner), and Retained Earnings (cumulative profit/loss). For corporations, you’ll have Common Stock and Retained Earnings instead.

Revenue (or Income) accounts track money earned by the business. This includes Sales Revenue (primary business income), Service Revenue (for service businesses), Other Income (interest earned, gain on asset sale), and potentially sub-categories like “Product Sales” and “Consulting Revenue” if the business has multiple revenue streams.

Expenses are costs incurred to run the business. The IRS provides standard expense categories including Advertising, Bank Fees, Insurance, Office Supplies, Rent, Utilities, Vehicle Expenses, Contract Labor, Professional Fees (legal, accounting), and many others. Your COA should include all relevant expense categories for the business type.

Standard COA structure for US small businesses

Here’s where QuickBooks and Xero make your life easier. They provide pre-built Chart of Accounts templates for different business types. When you create a new company file, you select the industry (consulting, retail, restaurant, e-commerce, etc.), and the software loads a standard COA appropriate for that industry.

For a typical US service-based small business (consultant, freelancer, or agency), the standard COA typically includes approximately 40–80 accounts, depending on complexity and industry, organized as follows:

Assets (1000-1999 numbering):

- 1000: Checking Account

- 1010: Savings Account

- 1200: Accounts Receivable

- 1500: Equipment (computer, office furniture)

- 1510: Accumulated Depreciation – Equipment

Liabilities (2000-2999):

- 2000: Accounts Payable

- 2100: Credit Card – [Bank Name]

- 2500: Loan – [Lender Name]

- 2600: Sales Tax Payable (only if the client sells taxable products or services)

Equity (3000-3999):

- 3000: Owner’s Equity (or Common Stock for corp)

- 3100: Owner’s Draw (or Distributions)

- 3900: Retained Earnings (automatically maintained by software)

Revenue (4000-4999):

- 4000: Service Revenue

- 4100: Product Sales (if applicable)

- 4900: Other Income

Expenses (5000-5999 or 6000-6999):

- 5000-5999: Cost of Goods Sold (if product business)

- 6000: Advertising & Marketing

- 6100: Bank Charges & Fees

- 6200: Insurance

- 6300: Office Supplies & Expenses

- 6400: Professional Fees (legal, accounting)

- 6500: Rent

- 6600: Software & Subscriptions

- 6700: Utilities (phone, internet, electricity)

- 6800: Vehicle Expenses

- 6900: Meals & Entertainment

Notice the numbering system: accounts are grouped by type in thousand-number ranges. This is standard US practice. Most accounting software can import/export COAs in this format, making it easier to work across different clients using similar structures.

Customizing for industry-specific bookkeeping needs for US businesses

While the standard Chart of Accounts works for simple service businesses, most clients need customization based on their industry and business model. Here are common adjustments you’ll make in U.S. small-business bookkeeping:

E-commerce businesses

Need detailed tracking for product, shipping, and platform fees. Add accounts such as:

• Inventory – [Product Category]

• Cost of Goods Sold – [Product Line]

• Shipping Supplies

• Shipping Expenses – [Carrier]

• Marketplace Fees (Amazon, eBay, Etsy)

• Payment Processing Fees (Stripe, PayPal, Square)

• Returns & Refunds

• Advertising – Amazon PPC

• Advertising – Facebook/Google Ads

Real estate professionals

Require commission and property-specific tracking. Add accounts like:

• Commission Income – [Property Type]

• Referral Fees Paid

• MLS & Licensing Fees

• Showing Expenses

• Client Gifts & Events

• Professional Photography & Staging

• Marketing – Virtual Tours

• Lockbox & Signage

• Transaction Coordinator Fees

Restaurants and food service

Need detailed cost tracking by category to control margins. Common accounts:

• Food Purchases – [Category: Meat, Produce, Dairy, etc.]

• Beverage Purchases – [Alcohol, Non-Alcohol]

• Kitchen & Dining Supplies

• Linen & Cleaning Service

• POS System Fees

• Credit Card Fees

• Delivery Commissions (DoorDash, Uber Eats)

Construction and contractors

Depend on job costing and material detail. Add accounts such as:

• Direct Labor – [Project]

• Materials – [Project or Category]

• Subcontractor Costs – [Trade]

• Equipment Rental

• Vehicle Fuel & Maintenance

• Permits & Fees

• Liability & Workers Comp Insurance

• Tools & Small Equipment

Each industry’s COA customization ensures reports reflect how money actually moves in that business. QuickBooks and Xero both support subaccounts or tracking categories to manage these details, though setup varies by platform.

Here’s my process for customizing a COA when onboarding a new client:

Step 1: Start with the software’s industry template for that business type.

Step 2: Review the client’s past financial records (bank statements, previous bookkeeping if available) to identify expense categories they actually use.

Step 3: Add specific accounts for their major expense categories (typically 5-10 additional custom accounts).

Step 4: Delete unused accounts from the template to avoid clutter. If they don’t have employees, remove payroll-related accounts. If they don’t carry inventory, remove COGS accounts.

Step 5: Establish sub-accounts for detailed tracking where needed. For example, under “Advertising & Marketing” you might create sub-accounts for “Advertising – Google Ads,” “Advertising – Facebook,” “Advertising – Print.”

Step 6: Document the COA structure in your client onboarding file so you maintain consistency.

A well-structured COA typically has 50-100 accounts for small businesses and 100-200 for medium-sized businesses. Too few accounts and you lose detail. Too many and it becomes unwieldy. Find the balance that provides useful reporting without excessive complexity.

How to Choose the Right Accounting Software for Your US Small Business Client’s Needs

Software selection is critical because it determines your efficiency as a bookkeeper, the quality of financial reports you can produce, and ultimately how much you can earn. Some software is easier to learn but limiting; others are powerful but complex. Let me guide you through the options that matter.

QuickBooks Online: The US Bookkeeping industry standard

QuickBooks Online (QBO) dominates the US small business market with approximately 70-80% market share according to industry estimates. This matters tremendously for your career because the majority of job postings and client opportunities will require QuickBooks knowledge.

QBO is cloud-based accounting software developed by Intuit. It handles everything from basic transaction entry to complex inventory management, multi-currency transactions, and project tracking. The interface is intuitive for beginners yet powerful enough for sophisticated businesses.

Key features that make QuickBooks Online the U.S. standard

1. Bank feeds that save hours every week

QBO automatically imports transactions from linked bank and credit card accounts. You simply review, categorize, and approve transactions instead of entering them manually. This automation is what makes cloud bookkeeping about 10× faster than spreadsheets or desktop accounting.

2. Invoicing and online payments built in

You can create branded invoices, send them by email, and let clients pay instantly via QuickBooks Payments. U.S. customers can pay by credit card or ACH bank transfer using the “Pay Now” button on the invoice, and payments automatically sync with your books.

3. Powerful, customizable reporting

QBO includes all standard financial reports—Profit & Loss, Balance Sheet, and Cash Flow—plus dozens of detailed management reports such as Profit & Loss by Customer, Sales by Product/Service, and Accounts Receivable Aging. Reports can be customized and scheduled for automatic email delivery.

4. Mobile access from anywhere

The iOS and Android apps let you send invoices, upload receipts, and monitor balances on the go. Clients can photograph receipts directly from their phone and have them categorized automatically.

5. Integrations with 650+ apps

QBO connects with leading tools like Stripe, PayPal, and Square for payments; Expensify and Dext for receipt capture; TSheets and Toggl for time tracking; HubSpot and Salesforce for CRM; and Shopify, Amazon, and WooCommerce for e-commerce management. This ecosystem is a major reason most U.S. small businesses prefer QBO over Xero or Wave.

QuickBooks Online U.S. Pricing (Effective July 1, 2025)

- Simple Start – $38/month: 1 user, basic income and expense tracking, invoicing, and bank connections

- Essentials – $75/month: 3 users, adds bill management and time tracking

- Plus – $115/month: 5 users, adds inventory tracking and project profitability

- Advanced – $275/month: 25 users, adds custom reporting, workflow automation, and enhanced analytics

- QuickBooks Online Accountant – Free: for accounting professionals managing multiple client accounts

Payroll Add-ons (U.S., July 2025):

- Core Payroll: $50 base/month + $6.50 per employee

- Premium Payroll: $88 base/month + $10 per employee

- Elite Payroll: $134 base/month + $12 per employee

For 90% of your small-business clients, Simple Start or Essentials will be sufficient. E-commerce or inventory-heavy businesses need Plus. Advanced is designed for larger or multi-location businesses.

Certification tip:

Intuit’s QuickBooks ProAdvisor Program offers free training and certification for bookkeepers. It takes roughly 20–30 hours to complete and adds you to the ProAdvisor Directory, where U.S. businesses search for certified professionals. Certification instantly boosts credibility and discoverability.

My recommendation:

Make QuickBooks Online your primary software focus. Learn it deeply, get certified, and position yourself as a QBO specialist. That single skill opens the door to over 70% of paid bookkeeping opportunities in the U.S. market.

Xero, FreshBooks, and Wave: Alternative Accounting Software for U.S. Small Businesses

While QuickBooks dominates, several alternatives serve specific niches. Understanding when to recommend alternatives makes you a better advisor to clients and opens additional market segments.

Xero is QuickBooks’ primary competitor with approximately 15-20% of the US small business market. Xero originated in New Zealand and is particularly popular with international businesses, businesses with strong UK/Australia connections, and accountants who prefer its interface.

Xero’s strengths include excellent bank reconciliation interface (many bookkeepers find it more intuitive than QBO), unlimited users at all pricing levels (QBO limits users by tier), beautiful modern interface, and strong multi-currency support. Xero integrates well with many apps and has a robust partner ecosystem.

When to recommend Xero: Businesses with international customers or multiple currencies, businesses where several people need access, clients who value interface aesthetics and user experience, businesses with UK/Australia connections where Xero is more common.

FreshBooks focuses on service-based businesses, freelancers, and consultants. Its strengths are invoicing and expense tracking with excellent time tracking integration. FreshBooks is less robust for complex accounting needs but excels at what it does.

When to recommend FreshBooks: Freelancers and consultants who bill by the hour, businesses where invoicing is the primary bookkeeping activity, clients who find QBO and Xero too complex, and very small businesses (under $100K revenue).

Wave is unique: completely free accounting software supported by payment processing fees and add-on services. Wave includes invoicing, expense tracking, receipt scanning, and financial reporting at no cost. They monetize through payment processing and payroll services.

When to recommend Wave: Brand new businesses with tight budgets, very small freelancers (under $50K revenue), businesses that don’t need advanced features, and clients willing to use Wave’s payment processing to access free software.

My strategic advice will be to learn QuickBooks Online first and become proficient. Then add Xero as your secondary software (takes 2-3 weeks to learn if you know QBO well because the concepts are the same, just different interfaces). This combination makes you competitive for 85-90% of US small business bookkeeping opportunities.

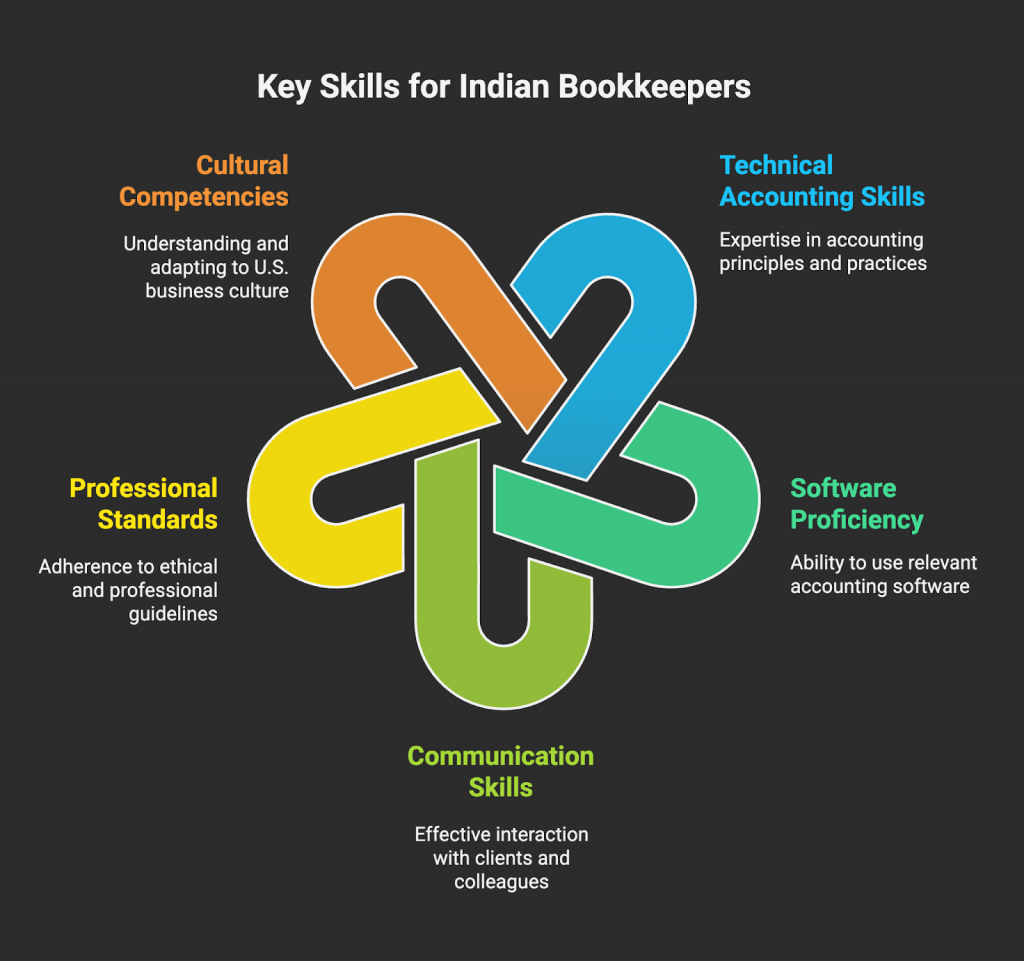

Essential Skills for Indian Bookkeepers Supporting U.S. Small Businesses

Beyond software knowledge, you need a specific skill set to succeed as a remote US bookkeeper from India. Let me outline what actually matters in the market.

Technical accounting skills: Double-entry bookkeeping fundamentals (debits/credits, journal entries), US GAAP basics (revenue recognition, matching principle, materiality), Financial statement preparation and interpretation, Reconciliation procedures (bank, credit card, accounts), Accruals and adjusting entries, Basic US tax knowledge (business expense categories, quarterly payment requirements).

Software proficiency: QuickBooks Online advanced features (inventory, projects, classes), Bank feed management and transaction categorization, Integration setup and management (payment processors, receipt apps), Report customization and scheduling, Multi-user access and permissions management.

Communication skills: Written English proficiency (email, chat, documentation), Ability to explain financial concepts to non-accountants, Professional client communication etiquette, Time zone coordination and availability management, Video conferencing confidence (Zoom, Google Meet).

Professional standards: Attention to detail and accuracy, Ability to meet deadlines consistently, Proactive problem-solving and question-asking, Confidentiality and data security awareness, Continuous learning mindset for software updates and best practices.

Cultural competencies: Understanding US business expectations and norms, Familiarity with US tax season (January-April) and quarterly deadlines, Knowledge of US holidays and business calendar, Patience with clients who aren’t financially sophisticated, Ability to build trust remotely across cultural differences.

The good news: none of these skills are out of reach. The accounting fundamentals you learned in BCom/MCom are universal. QuickBooks can be learned in 2-3 months of focused practice. Communication skills improve with practice and client interactions. Professional standards are about conscientiousness. That is a quality you can control.

Start with technical accounting and software skills. Add communication and professional polish through practice. Cultural competencies come through exposure and intentional learning about US business practices.

Phase 2: Daily Operations: Recording and Managing Transactions for US Small Businesses

Once your client’s bookkeeping foundation is set up, the real work begins: recording and managing daily transactions. This is where you’ll spend 60-70% of your bookkeeping time, and mastering efficient daily workflows is what separates $10/hour bookkeepers from $30/hour professionals.

The Transaction Recording System

Daily Bookkeeping Transactions for US Small Businesses

Let me walk you through what daily bookkeeping actually looks like for a typical US small business. Understanding this daily rhythm helps you estimate how long tasks take and quote accurate prices to clients.

For service-based businesses (consultants, freelancers, agencies), daily transactions typically include recording time worked on client projects (if billing hourly), Creating and sending invoices to clients, Recording payment receipts from customers, Entering business expense receipts (software subscriptions, office supplies, meals, travel), Recording credit card charges as they appear in bank feeds, Making note of any cash transactions if applicable.

A typical service business with $20,000-50,000 monthly revenue might have 30-80 transactions per month: 10-20 invoices sent, 15-30 expense receipts, 10-20 bank/credit card transactions, and 5-10 payments received. At intermediate speed, this takes 3-5 hours per month to record and categorize.

For product-based businesses (e-commerce, retail, wholesale), daily transactions include everything above plus recording inventory purchases from suppliers, Entering sales from various channels (website, Amazon, eBay, retail location), Recording shipping costs and supplies, Managing returns and refunds, Tracking cost of goods sold, Updating inventory quantities and values.

A product business with similar revenue might have 200-500 transactions per month due to higher transaction volume from multiple customer orders. This could take 10-15 hours monthly to manage properly, which is why product businesses pay more for bookkeeping services.

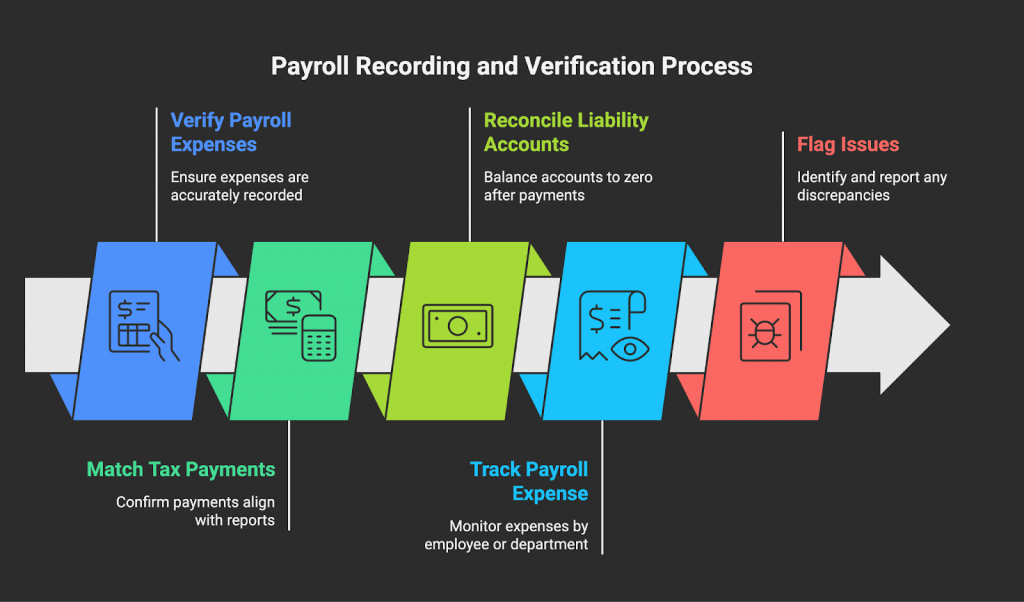

For businesses with employees, add payroll transactions: Processing payroll (typically semi-monthly or bi-weekly), Recording payroll taxes withheld and employer contributions, Paying payroll tax deposits (semi-weekly or monthly), Recording employee reimbursements, Managing benefits and deductions.

Your daily bookkeeping workflow should follow this sequence: Check bank and credit card feeds for new transactions. Download and categorize transactions in software. Attach digital receipts to corresponding transactions. Create invoices for services performed or products sold. Record customer payments received, Enter any transactions that don’t auto-import (cash transactions, checks), Make note of items needing follow-up or client clarification.

Most efficient bookkeepers batch-process transactions 2-3 times per week rather than daily. Monday, Wednesday, and Friday processing works well. You’re never more than 2-3 days behind, and batching is more efficient than daily processing. However, invoicing should happen immediately after service delivery or product shipment to maintain healthy cash flow for your clients.

Bookkeeping Source Documents: Invoices, Receipts, and Bank Statements for US Startups

Every transaction you record must be supported by source documents. It’s the physical or digital evidence that the transaction occurred. US bookkeeping and tax regulations require maintaining proper documentation, and you need to develop good habits around document management.

Invoices (customer invoices) are generated by the business when selling products or services. In QuickBooks or Xero, you create the invoice within the software, which generates a PDF you send to the customer. The invoice includes: Invoice number (sequential), Date issued, Customer name and address, Detailed description of products/services, Quantities and prices, Subtotal, Sales tax (if applicable), Total amount due, Payment terms (Net 30, Due on Receipt, etc.), Payment methods accepted.

When the customer pays, you record the payment against the invoice, which reduces Accounts Receivable and increases Cash. The software maintains a record of all invoices whether they’re paid, unpaid, and overdue.

Bills (vendor invoices) are invoices you receive from suppliers and service providers. When you receive a bill for office supplies, software subscriptions, utilities, etc., you should enter it into the software as a “Bill” (not directly as an expense). This creates an Accounts Payable entry. When you pay the bill, you record the payment, which reduces Accounts Payable and decreases Cash.

According to IRS recordkeeping requirements, businesses must keep all source documents supporting income and expenses for at least 3 years (7 years if substantial errors or fraud are possible). Digital copies are acceptable. You don’t need to keep physical paper.

Receipts document expenses and purchases. For every business expense, you should have a receipt showing: Vendor name, Date of purchase, Items purchased with description, Amount paid, Payment method. Receipts can be physical paper, email confirmations, or digital receipts.

Bank statements and credit card statements serve as primary source documents for all cash and credit transactions. In cloud bookkeeping, bank feeds automatically import transactions from connected accounts. However, you should still review monthly statements to ensure all transactions imported correctly and no discrepancies exist.

Contracts and agreements support larger transactions like equipment purchases, lease agreements, loan documents, and service contracts. Keep these in your client file system. You’ll reference them when recording payments or making adjusting entries.

Deposit slips and wire transfer confirmations document customer payments received. When a client pays by check or wire transfer, keep the confirmation as support for the deposit.

Your document management system should organize all source documents by month and transaction type. Most bookkeepers use folder structures like: Client Name → Year → Month → Invoices, Receipts, Bank Statements, Reports. Cloud storage (Google Drive, Dropbox, OneDrive) works well for remote bookkeeping. You can access client documents from anywhere while maintaining security.

Digital Receipt Management and Cloud Storage for Remote US Bookkeepers

As a remote bookkeeper in India serving US clients, effective digital receipt management is crucial. You can’t collect paper receipts from clients across 8,000 miles. Everything must be digital and cloud-based.

Here’s the system I recommend: Receipt scanning apps are essential. Apps like Expensify, Dext (formerly Receipt Bank), and Hubdoc let clients photograph receipts with their smartphones and automatically extract key data (date, vendor, amount). These apps integrate with QuickBooks and Xero, automatically matching receipts to imported bank transactions.

Walk new clients through setting up a receipt scanning app during onboarding. Show them: “Whenever you make a business purchase, immediately photograph the receipt using Expensify. The receipt will automatically appear in QuickBooks attached to the transaction. This takes 10 seconds and ensures we never lose documentation.”

For recurring expenses without receipts (software subscriptions, monthly services), save the email confirmation or take a screenshot of the charge confirmation page. Email confirmations count as valid documentation for IRS purposes.

Cloud storage organization should follow a consistent structure across all clients. Here’s the system I use:

/Client Name

/2025

/01-January

/Bank Statements

/Credit Card Statements

/Invoices Sent

/Bills Received

/Receipts

/Payroll

/02-February

[same subfolders]

/Financial Reports

/Monthly

/Quarterly

/Annual

/2024

[same structure]

/Setup Documents

/EIN Letter

/Operating Agreement

/Bank Account Info

This structure makes finding any document quick and intuitive. When the client’s CPA asks for “March 2025 bank statements,” you know exactly where they are.

Security is critical. Use encrypted cloud storage with two-factor authentication. Never store client financial documents on unprotected personal devices. If using Google Drive, ensure the client’s folder has restricted access (only you and the client, not “anyone with link”). Consider client-specific email addresses for sensitive communications rather than mixing client work with personal email.

Backup strategy: Cloud storage providers generally maintain their own backups, but I recommend monthly downloads of critical client documents to a local encrypted drive as additional protection. Financial data is irreplaceable. Redundancy is worth the effort.

Revenue Recording and Invoicing

Creating professional invoices for US clients

Invoice quality matters more than you might think. A professional, clear invoice gets paid faster, builds client trust, and reduces payment disputes. Let me show you what makes a strong US business invoice.

Essential invoice elements:

Header section should include your client’s business name, logo (if they have one), contact information (address, phone, email, website), and invoice number. The invoice number should be sequential and never repeat. QuickBooks and Xero handle this automatically with formats like “INV-1001,” “INV-1002,” etc.

Client information section includes the customer’s name, business name (if B2B), billing address, and any purchase order number they provided (some businesses require PO numbers for payment processing).

Invoice details are critical: Invoice date (when issued), Due date (based on payment terms), Detailed line items with descriptions, quantities, unit prices, and line totals, Subtotal, Sales tax if applicable with tax rate and jurisdiction, Total amount due, Payment status (Paid, Unpaid, Partial).

Payment information tells customers how to pay: Accepted payment methods (check, ACH transfer, credit card, PayPal, etc.), Bank details for ACH transfers (if applicable), Online payment link (QuickBooks Payments, Stripe, etc.), Where to send checks if accepted, Any early payment discounts or late payment penalties.

Professional touches that improve invoices: Clear descriptive line items (“Website Redesign – Homepage and About Page” not just “Services”), Itemized expenses if billing time and materials (“Research: 12 hours @ $75/hr”), Professional thank you message (“Thank you for your business!”), Contact information if customer has questions, Terms and conditions if applicable (work scope, refund policy).

QuickBooks and Xero both provide customizable invoice templates. Spend 30 minutes setting up your client’s template properly at the start. Add their logo, adjust colors to match their brand, ensure all necessary fields are included. This one-time setup ensures every invoice looks professional automatically.

Payment Terms and Invoice Due Dates for US Small Business Bookkeeping

Payment terms dictate when invoice payment is due and set customer expectations. Understanding standard US payment terms helps you guide clients and manage their accounts receivable effectively.

Common US payment terms:

Net 30 means payment is due 30 days after the invoice date. This is the most common term for B2B services and supplies. If you invoice on March 1st with Net 30 terms, payment is due April 1st.

Net 15 is used for faster payment, due 15 days after the invoice date. Often used by businesses with good cash flow management that want to reduce accounts receivable aging.

Due on Receipt means payment is expected immediately upon receiving the invoice. Common for small transactions, retail sales, and one-time service providers.

Net 60 or Net 90 are extended terms sometimes required by larger corporate customers. These longer terms favor the buyer but hurt the seller’s cash flow. Only accept these terms if the customer is highly creditworthy and the order size justifies the wait.

2/10 Net 30 is a discount term meaning pay within 10 days and take a 2% discount, or pay the full amount within 30 days. This incentivizes early payment. If an invoice for $1,000 offers 2/10 Net 30, the customer can pay $980 within 10 days or $1,000 within 30 days.

COD (Cash on Delivery) requires payment before or upon delivery of goods/services. Used with new customers, customers with payment history issues, or high-value transactions.

My recommendation for small business clients: Start with Net 15 or Net 30 for established customers with good payment history. Use Due on Receipt for new customers until they prove reliability. Consider offering 2/10 Net 30 if cash flow allows. Many customers appreciate discounts and will pay early to save money.

For international customers (relevant if your client serves international markets), Net 30 or Net 45 is standard to account for payment processing delays and currency conversion time.

Set payment terms consistently in your accounting software so every invoice automatically includes the proper due date. QuickBooks and Xero calculate due dates based on selected terms. If you choose Net 30 and invoice on March 1st, the software automatically sets the due date to March 31st.

Recording Customer Deposits and Advance Payments in US Bookkeeping

Some businesses collect deposits or advance payments before delivering products or services. Recording these correctly is important because they’re liabilities (you owe the customer work or a refund) until you fulfill the order.

Recording a customer deposit: When a customer pays a deposit (let’s say $500 down on a $2,000 project), you should NOT record this as revenue yet. Instead, record it as a liability called “Customer Deposits” or “Unearned Revenue.”

The entry is Debit Cash $500, Credit Customer Deposits $500.

When you complete the project and invoice the full $2,000, you reduce the deposit liability and apply it against the invoice:

- Debit Customer Deposits $500

- Debit Accounts Receivable $1,500 (the remaining balance owed)

- Credit Revenue $2,000

When the customer pays the remaining $1,500: Debit Cash $1,500, Credit Accounts Receivable $1,500.

This approach correctly recognizes revenue only when earned (accrual basis principle) and maintains accurate financial statements. If you incorrectly record the deposit as immediate revenue, you overstate income in the deposit month and understate it in the completion month.

QuickBooks handles this through the “Receive Payment” function with “Unapplied Cash Payment Income” or by using credit memos. Xero uses “Overpayment” functionality. Both systems make it easier than manual journal entries, but you need to understand the accounting logic behind the clicks.

Recording State-Specific Sales Tax for US Small Business Bookkeeping

Sales tax in the US is complex because it’s managed at the state level, not federally. Each state sets its own rules, rates, and filing requirements. Some states have no sales tax at all (Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon). Others have state, county, and city taxes that combine for total rates of 8-10%.

When businesses must collect sales tax:

A business must collect sales tax when they have nexus (significant presence) in a state and sell taxable products or services to customers in that state. Nexus can be established by: Physical presence (office, warehouse, store), Economic nexus (exceeding sales thresholds typically $100,000 annual sales in the state), Having employees in the state, Storing inventory in the state (common for Amazon FBA sellers).

What products and services are taxable: This varies by state, but generally: Physical products are usually taxable. Services are often exempt (but not always—some states tax specific services), Digital goods (software downloads, e-books) may or may not be taxable depending on state, Food and clothing may be exempt or taxed at reduced rates.

Recording sales tax in QuickBooks/Xero:

Modern accounting software handles sales tax automatically once configured. During setup, you specify: Which states the business has nexus in, the applicable tax rates in each jurisdiction, whether products/services are taxable or exempt.

When you create an invoice, QuickBooks automatically calculates and adds sales tax based on the customer’s location and the taxability settings. For a $1,000 product sale to a California customer (assume 8.5% combined rate), the software creates an invoice for $1,085 ($1,000 + $85 sales tax).

The accounting entry behind the scenes: Debit Accounts Receivable $1,085, Credit Sales Revenue $1,000, Credit Sales Tax Payable $85.

The $85 sales tax collected is a liability. You’re holding it temporarily for the state. When you pay the state quarterly or monthly (based on filing frequency), you reduce the Sales Tax Payable account:

Debit Sales Tax Payable $85 (or the total collected across all transactions), Credit Cash $85.

Sales tax filing and remittance:

States require businesses to file sales tax returns and remit collected tax on a schedule based on volume: Monthly (high-volume businesses), Quarterly (most small businesses), Annually (very low-volume businesses).

As a bookkeeper, your responsibilities typically include: Ensuring sales tax is correctly added to invoices, Reconciling Sales Tax Payable to ensure accuracy, Running sales tax reports before each filing deadline, Providing reports to the client or CPA who files the return, Recording the payment when remitted.

Many bookkeepers don’t actually file sales tax returns—that’s often handled by the CPA or the business owner using state websites. But you need to maintain accurate records and provide the data.

Important: if your client sells on Amazon, Amazon often collects and remits sales tax on behalf of sellers (called Marketplace Facilitator Tax Collection). This means the seller doesn’t collect tax on Amazon sales. You need to understand which sales channels auto-collect tax and which don’t, so you’re not double-collecting.

Expense Tracking and Categorization

Common expense categories for US startups

Understanding standard US business expense categories is essential because proper categorization affects tax deductions, financial reporting accuracy, and your ability to provide insights to clients. Let me walk you through the categories you’ll use most frequently.

Advertising & Marketing includes all promotional costs: Google Ads, Facebook/Instagram ads, Print advertising, Website development and hosting, SEO and content marketing services, Business cards and promotional materials, Trade show exhibits and booth costs, Sponsorships.

Auto & Vehicle expenses (if client uses vehicle for business): Fuel and oil, Repairs and maintenance, Insurance, Registration and licenses, Parking and tolls, Car washes, Lease payments (if leasing). Note: US allows either actual expense method or standard mileage rate (67 cents per mile in 2025 per IRS guidelines). Most small businesses use the simpler standard mileage method.

Bank Charges & Fees: Monthly account fees, Wire transfer fees, Credit card processing fees (Stripe, PayPal, Square), Overdraft fees, Check printing costs.

Contract Labor & Subcontractors: Payments to independent contractors, Freelancer fees, Subcontractor costs. Important: these are reported on Form 1099-NEC if over $600 annually. Track contractor payments separately for 1099 reporting.

Insurance: General liability insurance, Professional liability (E&O insurance), Property insurance, Business interruption insurance, Workers compensation (if employees), Health insurance (if providing to employees).

Legal & Professional Fees: Attorney fees, Accounting and bookkeeping fees (yes, your fees go here!), Consulting fees, Business licenses and permits.

Meals & Entertainment: Client meals (50% deductible per IRS rules), Team meals, Business travel meals. Important: Personal meals and entertainment are NOT deductible. Only business-related meals qualify, and only at 50% of cost.

Office Expenses & Supplies: Office supplies (pens, paper, folders), Postage and shipping, Printer ink and toner, Small office equipment (under $2,500), Cleaning supplies.

Rent: Office rent, Warehouse rent, Storage unit rent, Equipment rental. If working from home, this could include home office deduction (IRS Form 8829).

Software & Subscriptions: QuickBooks or Xero subscription, Project management tools (Asana, Monday.com), Communication tools (Zoom, Slack), Email marketing (Mailchimp), CRM (HubSpot, Salesforce), Any SaaS tools used in business operations.

Travel: Airfare, Hotels, Rental cars, Taxis and ride-sharing, Travel meals (tracked separately for 50% deduction). Must be business-related travel to be deductible.

Utilities: Internet service, Phone service (business line or business percentage of personal phone), Electricity (if separate business location), Water and trash service.

Wages & Payroll: Employee salaries, Payroll taxes (employer portion), Employee benefits, Worker’s compensation insurance.

When categorizing transactions, be specific but not excessive. A COA with 40-60 expense accounts provides useful detail without becoming unmanageable. Create sub-accounts only when you need to track something separately—for example, “Advertising – Google Ads” and “Advertising – Facebook Ads” as sub-accounts under “Advertising & Marketing” if the client wants to compare ROI across platforms.

Deductible vs non-deductible expenses in US Bookkeeping (IRS rules)

Not all business expenses are tax-deductible, and understanding the difference protects your clients from IRS problems. While you’re not expected to be a tax expert, knowing the basics helps you categorize questionable expenses appropriately and flag issues for the CPA.

Ordinary and necessary test: According to IRS Publication 535 (Business Expenses), an expense must be both “ordinary” and “necessary” to be deductible. “Ordinary” means common and accepted in your industry. “Necessary” means helpful and appropriate for your business. The expense doesn’t have to be required. They just need to be helpful and reasonable.

Fully deductible expenses include:

- Office supplies and equipment

- Business insurance premiums

- Software and subscriptions used for business

- Advertising and marketing

- Professional fees (legal, accounting, consulting)

- Business interest on loans

- Rent for business space

- Contract labor payments

- Business phone and internet

- Trade publications and memberships

- Employee wages and benefits

- State and local business taxes

Partially deductible expenses:

- Meals and entertainment: Generally 50% deductible. If you take a client to lunch and spend $100, only $50 is deductible.

- Business vehicle: Either actual expenses or the standard mileage rate can be deducted, but only for business use percentage. If a vehicle is 60% business and 40% personal, only 60% of costs are deductible.

- Home office: Deductible based on percentage of home used exclusively for business. A 200 sq ft office in a 2,000 sq ft home can deduct 10% of home expenses (mortgage interest, property tax, utilities, and insurance).

Never deductible expenses:

- Personal expenses (personal meals, personal shopping, personal travel)

- Fines and penalties (traffic tickets, IRS penalties, late fees to government)

- Political contributions and lobbying

- Commuting costs from home to regular office

- Most clothing (unless uniforms or protective gear)

- Club memberships for recreation or leisure (country clubs, athletic clubs)

- Personal life insurance premiums

Questionable expenses that need careful handling:

Luxury items might be challenged: Is the $5,000 executive office chair necessary, or is it extravagant? Is the first-class airfare justified, or should the client fly economy? Generally, as long as the expense has business purpose and isn’t wildly unreasonable, it’s deductible. But document the business purpose clearly.

Mixed-use expenses (partially business, partially personal) should be allocated appropriately. The client’s cell phone might be 70% business and 30% personal. Deduct only the business portion. Document the allocation method in case of audit.

Startup costs (expenses before the business officially begins operating) have special rules. First $5,000 can be immediately deducted, remainder is amortized over 15 years. These go in a separate “Startup Costs” account, not regular expense accounts.

Capital expenditures (equipment, vehicles, and buildings costing over $2,500) are generally not immediately deductible. They’re recorded as assets and depreciated over their useful life (5 years for computers, 7 years for office furniture, 27.5 years for residential rental property, 39 years for commercial property). However, Section 179 allows immediate deduction of up to $1,220,000 (2025 limit) for qualifying equipment purchases.

As a bookkeeper, create an “Ask CPA” expense account for questionable items. When you encounter an expense that seems personal or you’re uncertain about, categorize it to “Ask CPA” and flag it for review. This protects the client while demonstrating your diligence.

Common mistakes to avoid: Don’t categorize personal expenses as business expenses (even if the client asks, politely refuse and explain it’s not deductible). Don’t guess on large or unusual expenses. Ask the client for clarification or flag for CPA. Don’t mix deductible and non-deductible items in the same category. Keep them separate for clean tax preparation.

Recording and Reconciling Credit Card Transactions for US Small Businesses

Business credit cards are essential tools for US small businesses, offering cash flow flexibility and rewards programs. As a bookkeeper, you’ll manage credit card transactions almost as much as bank transactions. Here’s how to handle them properly.

Setting up credit cards in accounting software:

Create a separate account for each business credit card under the Liabilities section of your COA. Name it clearly: “Credit Card – Chase Ink Business” or “Credit Card – American Express Blue.” Connect the credit card to your accounting software’s bank feed so transactions auto-import, just like checking account transactions.

Recording credit card charges:

When transactions import through bank feeds, you categorize each charge to the appropriate expense account. For example: $49.99 charge to Adobe = categorize to “Software & Subscriptions,” $87.50 charge to restaurant = categorize to “Meals & Entertainment” with note “Client meeting with John Smith.”

The accounting entry behind the scenes: Debit Software & Subscriptions $49.99, Credit Credit Card Payable $49.99. This increases both the expense (debit) and the liability owed on the credit card (credit).

Recording credit card payments:

When the client pays the credit card bill, you record a transfer from the checking account to the credit card account. In QuickBooks, use “Transfer” not “Expense” for this transaction. The entry is: Debit Credit Card Payable (reduces the liability), Credit Checking Account (reduces cash).

Never categorize a credit card payment as an expense—that would double-count the expenses (you already categorized them when charges occurred). Credit card payments are simply transfers reducing the liability.

Reconciling credit card accounts:

Reconciliation works the same as bank reconciliation. At least monthly (ideally when the statement arrives): Access the credit card statement (online or PDF), In QuickBooks/Xero, begin reconciliation for the credit card account, Enter the statement ending date and ending balance, Mark all transactions that appear on the statement, Verify the difference is zero, Complete the reconciliation.

If the reconciliation doesn’t balance, common causes include: Missing transactions that didn’t auto-import, Duplicate transactions entered manually and also imported, Transactions categorized to wrong account, Returns or credits not recorded, Payment not recorded properly.

Credit card rewards and cashback:

When clients redeem credit card rewards or receive cashback, record it as “Other Income” or create a specific account called “Credit Card Rewards.” This is technically taxable income but often minimal amounts. If rewards are redeemed as statement credits, record the credit directly against the credit card liability (reduces what’s owed).

Common credit card issues:

Personal charges on business credit cards happen frequently with small business owners. When you spot clearly personal charges (grocery stores, retail shopping, personal entertainment), categorize them to “Owner’s Draw” or “Shareholder Distribution” rather than business expenses. Document with notes: “Personal expense – transferred to owner draw.”

Split transactions where one credit card charge covers multiple expense categories should be split properly. A $500 purchase at an office supply store might be $300 office supplies + $200 computer equipment. Most software allows splitting transactions into multiple categories.

Foreign transaction fees (typically 1-3% on international purchases) should be categorized to “Bank Charges & Fees” separately from the main purchase.

Recurring charges for subscriptions should be reviewed annually. I’ve found numerous cases where clients paid for software they no longer used. Part of your value-add as a bookkeeper is flagging these: “I notice you’re paying $99/month for [Software X]. Are you still using this?”

Managing Petty Cash and Employee Reimbursements in US Bookkeeping

Petty cash and employee reimbursements are less common in modern US businesses (most use credit cards), but you still need to understand proper handling.

Petty cash is a small amount of physical cash kept on hand for minor expenses: parking meters, small office supplies, emergency purchases, tips and delivery fees. Most businesses maintain $100-500 in petty cash.

Setting up petty cash:

Create a “Petty Cash” account under Assets in your COA. When the business first establishes petty cash, record the transfer: Debit Petty Cash $200, Credit Checking Account $200.

Recording petty cash expenses:

When cash is spent, record the expense with supporting receipts. For example, $15 spent on office supplies: Debit Office Supplies $15, Credit Petty Cash $15. This reduces the petty cash balance and increases the expense account.

Replenishing petty cash:

When petty cash runs low, the client writes a check to replenish it back to the original amount. If the petty cash account shows $50 remaining (after $150 spent), write a check for $150 to bring it back to $200. The entry is Debit Petty Cash $150, Credit Checking Account $150.

Important: you don’t record the expenses when replenishing. You recorded them as they occurred. The replenishment simply refills the cash fund.

Employee reimbursements occur when employees pay business expenses personally and request reimbursement. Common examples: Mileage for business driving in a personal vehicle, travel expenses paid personally (hotels, meals, flights), and office supplies purchased with personal funds.

Recording reimbursements:

The proper method uses Accounts Payable: Create a bill to the employee for the reimbursable amount (categorized to appropriate expense accounts). When you pay the employee, record the payment against the bill, just like paying a vendor.

The entries are: When creating bill: Debit [various expense accounts], Credit Accounts Payable – Employee Name

When paying an employee: Debit Accounts Payable – Employee Name, Credit Checking Account.

This method properly tracks what’s owed to employees and ensures reimbursements show separately from regular expenses in reports.

Mileage reimbursements for US businesses use the IRS standard mileage rate (67 cents per mile in 2025). Employees should submit mileage logs with dates, destinations, business purposes, and miles driven. Calculate: Miles × Rate = Reimbursement Amount.

Approval and documentation standards:

Establish clear reimbursement policies with clients: All reimbursement requests require receipts, Mileage requires detailed log, Reimbursement requests submitted within 30 days of expense, Manager approval before reimbursement processed.

As the bookkeeper, you verify documentation is complete before processing reimbursements. Missing receipts or unclear business purpose? Request clarification from the employee before reimbursing.

Accounts Payable and Receivable Management

Managing vendor bills and payment schedules in US Small Business Bookkeeping

Accounts Payable (AP) management—tracking what your client owes to vendors and ensuring bills are paid on time—is a core bookkeeping responsibility. Strong AP management helps clients maintain good vendor relationships, avoid late fees, and manage cash flow strategically.

Entering bills correctly:

When a vendor bill arrives (email PDF, paper bill, online statement), enter it as a “Bill” in QuickBooks/Xero, not directly as an expense. This creates an Accounts Payable entry: Debit [appropriate expense account], Credit Accounts Payable – [Vendor Name].

Include all relevant details: Vendor name, Bill date, Due date (based on payment terms), Bill number (vendor’s invoice number), Amount, Expense categories (split across multiple accounts if necessary), Attach the bill PDF to the transaction in the software.

Why enter bills instead of directly recording expenses?

Recording bills separately from payments provides several benefits: You see what’s owed at any moment (liability tracking), You can print “Unpaid Bills” reports showing cash needed, You avoid accidentally paying the same bill twice, You can time payments strategically (pay early for discounts, or conserve cash by paying on due date), Your balance sheet accurately reflects liabilities.

Payment prioritization:

Not all bills need immediate payment. Strategic AP management pays bills in priority order: Priority 1: Payroll taxes and government obligations (serious penalties for late payment), Priority 2: Bills with early payment discounts (pay within discount period for savings), Priority 3: Essential services (utilities, rent, critical software), Priority 4: Vendors you rely on regularly (maintain good relationships), Priority 5: One-time vendors and non-critical expenses (can wait until due date if cash is tight).

Creating a bill payment schedule:

I recommend a weekly bill payment schedule: review all unpaid bills, identify which are due within the next 7-10 days, check cash available in the checking account, prepare payments (checks or ACH), record payments in software, send payments to vendors.

This weekly rhythm prevents last-minute scrambles, late payments, and overdrafts. You’re always aware of upcoming obligations and can alert clients if cash flow is insufficient to cover scheduled payments.

Recording bill payments:

When paying a bill, use the “Pay Bills” function in QuickBooks/Xero. Select the bill(s) being paid, choose the bank account funds come from, enter the payment date, select payment method (check, ACH, credit card). The software records: Debit Accounts Payable – [Vendor Name], Credit Checking Account.

This reduces the AP liability and reduces cash, properly reflecting the transaction. The software also marks the bill as “Paid” so you don’t pay it again accidentally.

Handling credits and refunds:

When vendors issue credits (for returns, overpayments, or errors), record them as “Vendor Credits” in your software. Then apply the credit against future bills from that vendor. This reduces what you owe and maintains accurate vendor balances.

Common AP mistakes:

Paying bills directly as expenses without entering as bills first (loses liability tracking), Paying the same bill twice because it wasn’t marked paid in software, Missing early payment discounts because bills weren’t reviewed timely, Not tracking due dates resulting in late fees, Recording bill payments as new expenses instead of payments against AP.

Tracking customer payments and overdue invoices for US Bookkeepers

Accounts Receivable (AR) management, tracking what customers owe your client and ensuring timely payment, directly impacts cash flow. Strong AR management turns invoices into cash faster, which is often the difference between business success and failure.

Recording customer payments:

When a customer pays an invoice, record the payment in QuickBooks/Xero using the “Receive Payment” function. Select the customer, identify which invoice(s) the payment covers, enter the payment date and amount, choose the payment method (check, ACH, or credit card), and select the bank account where funds were deposited.

The software automatically creates the entry: Debit Checking Account (or Undeposited Funds if using that feature), Credit Accounts Receivable – [Customer Name].

This reduces the AR asset and increases cash, reflecting that you now have the money the customer owed.

Undeposited Funds account:

QuickBooks includes an “Undeposited Funds” account that’s useful when you receive multiple payments and deposit them together. When you receive Payment 1 ($500) and Payment 2 ($800): record both to Undeposited Funds. When you make a single bank deposit of $1,300, create a Bank Deposit transaction in QuickBooks transferring the two payments from Undeposited Funds to Checking Account.

This ensures your QuickBooks deposits match your bank statement deposits exactly, making reconciliation easier. Xero handles this differently with its “reconcile” function matching multiple payments to a single deposit.

Tracking overdue invoices:

Run an Accounts Receivable Aging Report at least weekly. This report groups unpaid invoices by age: Current (not yet due), 1-30 days overdue, 31-60 days overdue, 61-90 days overdue, and 90+ days overdue.