Complete guide to independent director applicability in India: learn when Companies Act 2013 & SEBI LODR 2015 require listed & unlisted companies to appoint independent directors, thresholds, exemptions & penalties.

Table of Contents

Independent directors play a crucial role in strengthening corporate governance frameworks across Indian companies, acting as impartial voices that balance management interests with stakeholder protection.

However, not every company is required to appoint independent directors—the applicability depends on specific criteria related to company type, financial thresholds, and regulatory frameworks.

Understanding when a company must appoint independent directors is essential for maintaining compliance with the Companies Act, 2013, and SEBI regulations, avoiding penalties, and building investor confidence.

This comprehensive guide examines the complete legal framework governing independent director applicability in India.

I’ll walk you through the specific requirements for different company types, explain how Companies Act and SEBI regulations interact, clarify exemptions and special situations, and provide actionable compliance timelines.

Whether you’re a company secretary ensuring regulatory compliance, a CFO evaluating governance requirements, a retired professional looking for a seat in the board as an Independent Director or a legal professional advising clients on board composition, you’ll find the practical guidance you need to determine if and when independent directors are mandatory for your organization.

What does “independent director applicability” mean under Indian corporate law?

Independent director applicability refers to the legal determination of whether a company is required to appoint independent directors to its board under Indian law.

This determination is governed primarily by Section 149 of the Companies Act, 2013 and the SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015.

The concept encompasses identifying which categories of companies must comply, how many independent directors are required, and what minimum board composition ratios must be maintained.

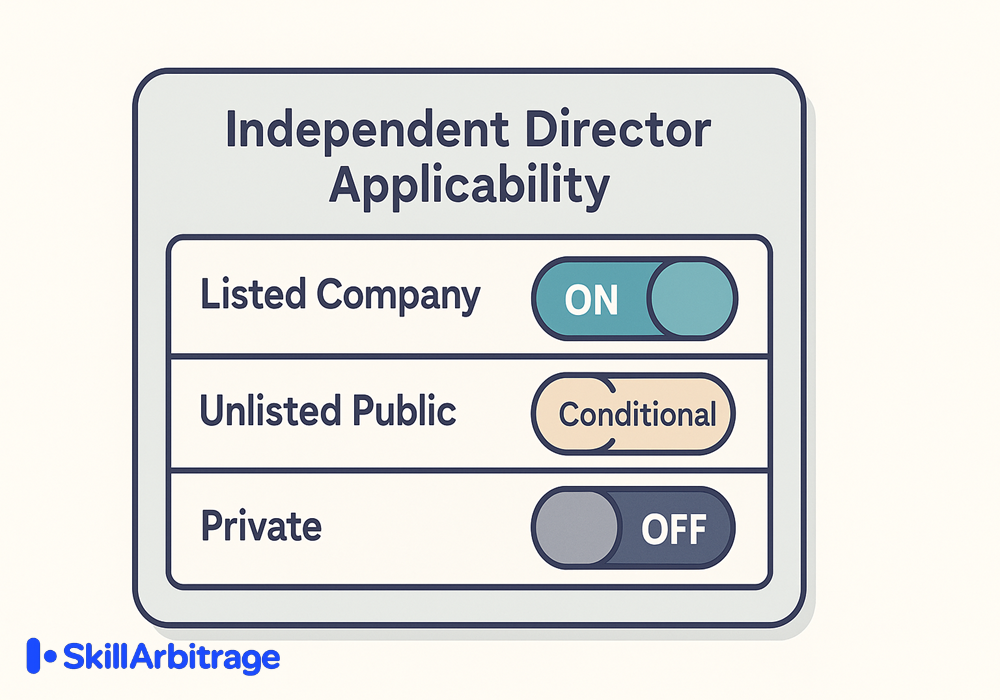

The applicability framework varies significantly based on company characteristics—listed public companies face mandatory requirements regardless of size, while unlisted public companies must meet specific financial thresholds related to paid-up capital, turnover, or outstanding borrowings.

Private companies are generally exempt unless subject to specific governance regulations, and certain categories like wholly-owned subsidiaries and dormant companies may qualify for exemptions even when they meet applicable thresholds.

Understanding these nuances helps companies proactively assess their obligations rather than discovering compliance gaps during audits or regulatory reviews.

Why are independent directors required — governance rationale and objectives?

The requirement for independent directors emerged from India’s commitment to strengthening corporate governance following global corporate scandals and domestic governance failures in the early 2000s.

Independent directors serve as impartial watchdogs who bring objective judgment to board deliberations, free from management influence or conflicts of interest that could compromise decision-making.

Their presence helps balance the power dynamics between controlling shareholders, management, and minority stakeholders, ensuring that board decisions reflect diverse perspectives rather than narrow interests.

Beyond regulatory compliance, independent directors fulfill critical governance functions that protect all stakeholders.

They oversee financial reporting integrity, evaluate management performance objectively, approve related-party transactions without bias, and ensure that companies operate within legal and ethical boundaries.

For minority shareholders and investors, independent directors provide assurance that their interests receive consideration in strategic decisions. For companies themselves, having independent directors enhances credibility with lenders, investors, and business partners while promoting long-term sustainable growth over short-term profit maximization that might benefit only controlling shareholders.

Professionals interested in serving on company boards can enhance their readiness through the Independent Director Course, which provides structured training on governance, board responsibilities, and compliance oversight.

What is the legal framework governing independent director applicability?

The legal framework governing independent director applicability in India operates through a dual regulatory structure: the Companies Act, 2013 establishes baseline requirements for all applicable companies, while the SEBI (LODR) Regulations, 2015 impose additional obligations specifically on listed entities.

Understanding both frameworks is essential because listed companies must satisfy the more stringent requirements when provisions conflict, while unlisted companies need only comply with Companies Act provisions. The Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) oversees Companies Act enforcement, whereas SEBI regulates listed company compliance, creating two parallel enforcement mechanisms with distinct penalty structures and reporting obligations.

What are the legal provisions under the Companies Act, 2013?

Section 149 of the Companies Act, 2013 forms the foundation of independent director requirements in India.

Specifically, Section 149(4) mandates that every listed public company must have at least one-third of its total directors as independent directors, with any fraction in that one-third being rounded up to one. For example, if a listed company has 10 directors, it must appoint at least 4 independent directors (one-third of 10 equals 3.33, rounded up to 4).

For unlisted public companies, Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 establishes specific financial thresholds that trigger the independent director requirement.

Unlisted public companies must appoint at least two independent directors if they meet any one of the following criteria:

(1) paid-up share capital of ₹10 crore or more,

(2) turnover of ₹100 crore or more, or

(3) aggregate outstanding loans, debentures, and deposits exceeding ₹50 crore.

These thresholds are calculated based on the last audited financial statements, meaning companies must evaluate their compliance status annually after finalizing accounts.

Section 149(6) defines who qualifies as an independent director by establishing stringent independence criteria. An independent director must be a person of integrity with relevant expertise and experience, must not be a promoter or related to promoters or directors, and cannot have any pecuniary relationship with the company exceeding prescribed limits. The definition specifically prohibits persons who held key managerial positions in the preceding three financial years or were associated with the company’s auditors, legal advisors, or consultants during that period. This comprehensive definition ensures that independent directors maintain genuine independence from management influence.

To understand the eligibility process and examination requirements for aspiring independent directors, read our detailed guide on the Independent Director Exam.

The Companies Act also establishes procedural requirements for independent director appointments. Section 149(10) limits independent directors to a maximum term of five consecutive years, with eligibility for reappointment for one additional five-year term through special resolution. Section 149(11) prevents any person from serving as an independent director for more than two consecutive terms, though they become eligible for reappointment after a three-year cooling-off period. These tenure limitations ensure board refreshment and prevent independent directors from becoming too aligned with management over extended periods.

What are the independent director requirements under SEBI (LODR) Regulations, 2015?

The SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015, commonly referred to as SEBI LODR, establishes additional independent director requirements specifically for listed entities. Regulation 17(1)(b) mandates that listed entities maintain a board composition with at least one-third independent directors, aligning with the Companies Act requirement but applying exclusively to entities with listed equity shares. However, when the chairman of a listed company is an executive director or is related to a promoter, the requirement increases to at least half of the board comprising independent directors.

SEBI Regulation 17(1E) also requires that any independent director vacancy must be filled within three months from the date of vacancy, ensuring continuous compliance with minimum board composition requirements.

Regulation 17A of SEBI LODR prescribes additional caps on the number of directorships for listed entities, which are more restrictive than the general limits in Section 165 of the Companies Act.

Regulation 25 of SEBI LODR indeed governs tenure, meetings, performance evaluation, resignation, and role of independent directors. It includes clauses on separate meetings, training, appointment limits, resignation process, and liability clarification.

SEBI LODR also mandates specific disclosure requirements regarding independent directors. Listed entities must disclose the appointment, resignation, or removal of independent directors to stock exchanges within prescribed timelines, provide detailed reasons for resignations, and confirm whether the resigning director has raised any concerns about the company’s governance.

Regulation 25(8) & (9) requires the board of a listed entity to annually verify and disclose that all independent directors meet the independence criteria laid down under Regulation 16(1)(b), while Regulation 46 mandates disclosure of directors’ skills and competencies on the company’s website.

How do the Companies Act and SEBI LODR frameworks differ in approach and scope?

The Companies Act 2013 and SEBI LODR Regulations 2015 differ fundamentally in their scope of application and enforcement mechanisms. The Companies Act applies universally to all companies incorporated in India—listed, unlisted, public, and private—with specific provisions triggered based on company characteristics.

In contrast, SEBI LODR applies exclusively to entities that have listed their equity shares, debt securities, or other specified securities on recognized stock exchanges, making it a more specialized regulatory framework targeting market-facing entities where investor protection concerns are heightened.

The enforcement approaches also differ significantly. The Ministry of Corporate Affairs enforces Companies Act provisions through the Registrar of Companies, and adjudication through the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT).

SEBI enforces LODR provisions through stock exchange monitoring and SEBI adjudication mechanisms, with penalties including fines, suspension of trading, and potential delisting for persistent non-compliance. Listed companies must therefore maintain dual compliance—meeting both MCA requirements for their corporate existence and SEBI requirements for their listed status.

When conflicts arise between the two frameworks, listed companies must follow the more stringent requirement. For instance, if Companies Act requires one-third independent directors while a specific SEBI provision requires half the board to be independent (in cases where the chairman is an executive director related to a promoter), the SEBI requirement prevails for listed companies. Similarly, the SEBI limit of seven directorships in listed entities operates independently of the Companies Act’s general twenty-company directorship limit, meaning an individual must comply with both restrictions simultaneously.

The reporting and disclosure obligations under each framework also differ substantially. Companies Act requires filings with the ROC through forms like DIR-12 for director appointments and removals, with prescribed timelines typically within 30 days of board resolutions. SEBI LODR mandates real-time disclosures to stock exchanges—appointment or resignation of independent directors must be disclosed within 24 hours under Regulation 30, with detailed reasons and implications shared with shareholders. This dual reporting creates additional administrative burden for listed companies but provides greater transparency to market participants.

What are the exemptions and relaxations applicable?

Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 provides specific exemptions for three categories of unlisted public companies even when they meet the financial thresholds:

(1) joint venture companies,

(2) wholly-owned subsidiaries, and

(3) dormant companies as defined under Section 455 of the Companies Act.

Additionally, if a company that was previously required to appoint independent directors ceases to meet the applicability criteria for three consecutive financial years, it is no longer required to comply with independent director provisions until it again meets any of the threshold conditions.

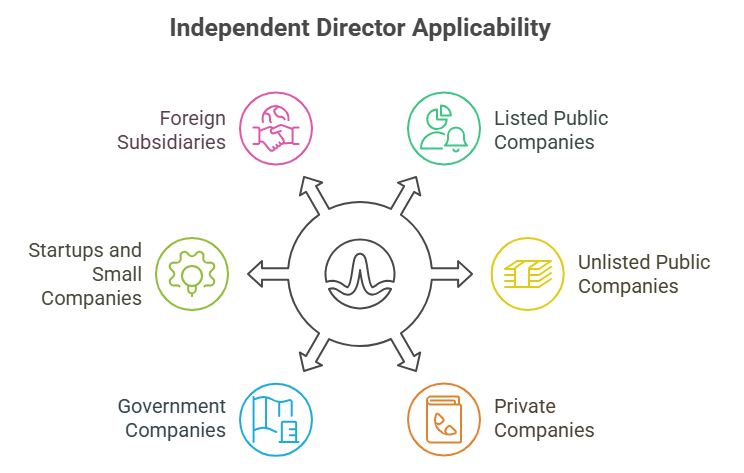

Independent director applicability based on company type

Understanding independent director requirements requires examining applicability through the lens of company type and classification under Indian corporate law.

The legal framework creates distinct compliance tiers:

- listed public companies face mandatory requirements regardless of size,

- unlisted public companies must evaluate financial thresholds annually,

- private companies generally remain exempt unless specific governance rules apply, and

- special categories like government companies and foreign subsidiaries follow modified frameworks.

Each company type presents unique compliance considerations that determine not just whether independent directors are required, but how many must be appointed and what governance structures must be established.

What is the requirement for listed public companies?

Listed public companies face the most stringent independent director requirements under Indian law.

Like I discussed above, Section 149(4) of the Companies Act, 2013 mandates that every listed public company must have at least one-third of the total number of directors as independent directors, with any fractional number rounded up to one.

The requirement applies automatically upon listing—the moment a company’s shares are listed on any recognized stock exchange in India, it must ensure compliance with independent director provisions. There are no exemptions based on market capitalization, trading volume, or company size for this fundamental requirement. Even if a company lists through an initial public offering (IPO) with minimal public shareholding or lists on the SME platform of stock exchanges, the one-third independent director requirement applies from the date of listing. Companies planning IPOs must therefore ensure board composition compliance before listing to avoid immediate regulatory violations.

SEBI LODR Regulation 17 reinforces this requirement and adds complexity in specific situations. When the chairperson of a listed company is an executive director or is related to the promoter or a person occupying management positions at the board level or one level below the board, at least half of the board must comprise independent directors. For example, if a listed company’s founder serves as both chairman and CEO (an executive chairperson), and the board has ten directors, at least five must be independent directors rather than the standard four required under the one-third rule.

Listed companies must also satisfy additional committee composition requirements that indirectly affect independent director numbers.

- The Audit Committee must comprise at least three directors, with a majority being independent under Section 177 of the Companies Act and at least two-thirds being independent under Regulation 18(1)(b) of SEBI LODR.

- Regulation 19(1)(c) (Nomination & Remuneration Committee): requires at least 2/3rd independent directors.

- Regulation 20(2A) (Stakeholders Relationship Committee): requires at least three directors with at least one independent.

- Regulation 21(2) of SEBI LODR mandates that the Risk Management Committee have at least three members, a majority from the board, including one independent director; and where SR equity shares exist, two-thirds must be independent.

If a listed company’s board has only the minimum one-third independent directors, it may struggle to populate the committees adequately while leaving sufficient independent directors for other committees like the nomination and remuneration committee.

Practical board design for listed companies often results in independent directors comprising 40-50% of the board to ensure all committee composition requirements are met comfortably.

What are the requirements for unlisted public companies (capital, turnover, and borrowing thresholds)?

Unlisted public companies face conditional independent director requirements based on three distinct financial thresholds established under Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014.

Unlike listed companies where the requirement is automatic, unlisted public companies must evaluate their compliance obligation annually based on their audited financial statements. If an unlisted public company meets even one of the three threshold criteria, it must appoint at least two independent directors to its board.

Threshold 1: Paid-up share capital of ₹10 crore or more

The first threshold examines the company’s paid-up share capital as reflected in the last audited financial statements.

Paid-up share capital represents the actual amount shareholders have paid for shares issued by the company, not the authorized capital mentioned in the memorandum of association. For example, if a company has authorized capital of ₹20 crore but has issued shares worth only ₹8 crore and received full payment, its paid-up capital is ₹8 crore—below the threshold. However, if the company issues additional shares worth ₹3 crore during the financial year, bringing paid-up capital to ₹11 crore, it crosses the threshold when those financial statements are audited and must appoint two independent directors.

Companies must include all classes of share capital in this calculation—equity shares, preference shares, and any other shares issued and paid-up are aggregated to determine total paid-up capital. Premium amounts received on shares are not included in paid-up share capital but are credited to the securities premium account, so a company that issues ₹5 crore worth of shares at a premium of ₹5 crore (collecting ₹10 crore total) has only ₹5 crore paid-up capital for this threshold calculation. This distinction is crucial for startups and growth companies that often raise capital at high premiums.

Threshold 2: Annual Turnover of ₹100 Crore or More

The second threshold evaluates annual turnover as disclosed in the last audited financial statements. Turnover refers to the gross revenue from operations before deducting any expenses, discounts, or returns—essentially the total sales or income generated from the company’s business activities. For a manufacturing company, turnover includes sales of goods; for a service company, it includes service revenue; for a trading company, it includes revenue from trading activities. Companies following Indian Accounting Standards (Ind AS) or previous Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) report this figure as “Revenue from Operations” in their profit and loss statement.

The ₹100 crore turnover threshold is calculated based on standalone financial statements of the unlisted public company, not consolidated statements including subsidiaries. If an unlisted public company has three subsidiaries and the parent company’s standalone turnover is ₹80 crore while consolidated group turnover exceeds ₹200 crore, the parent company does not meet the threshold based on its own financials. However, each subsidiary that is itself an unlisted public company must separately evaluate whether its standalone turnover exceeds ₹100 crore, triggering its own independent director requirement.

Companies approaching the ₹100 crore threshold must plan ahead because turnover can fluctuate significantly year-over-year based on business conditions. A company with ₹95 crore turnover in one year might cross ₹100 crore the next year due to business growth or a single large contract, triggering the independent director requirement. Once audited financial statements confirm turnover exceeds ₹100 crore, the company must appoint independent directors even if it expects lower turnover in the subsequent year—the requirement is based on historical audited figures, not future projections.

Threshold 3: Outstanding Loans, Debentures, and Deposits Exceeding ₹50 Crore

The third threshold examines the aggregate of outstanding loans, debentures, and deposits as reported in the last audited financial statements. This is the most complex threshold because it requires aggregating multiple liability categories from the balance sheet. “Outstanding loans” include term loans from banks and financial institutions, working capital facilities utilized, and loans from related parties or other companies. “Debentures” include both convertible and non-convertible debentures issued by the company that remain outstanding (not yet redeemed). “Deposits” refer to deposits accepted from the public under the Companies (Acceptance of Deposits) Rules, 2014, not bank deposits owned by the company.

The rule specifies “aggregate outstanding” meaning all three categories are added together to determine if the total exceeds ₹50 crore. For example, if an unlisted public company has ₹30 crore in bank loans, ₹15 crore in outstanding debentures, and ₹8 crore in public deposits, the aggregate is ₹53 crore, exceeding the threshold and triggering the two independent director requirement. Companies must use the balance sheet date figures from the last audited financial statements, not the current outstanding amounts, for this evaluation.

Importantly, this threshold focuses on borrowed funds and public deposits, not trade payables, advance payments from customers, or other operational liabilities. A company with ₹100 crore in trade payables to suppliers but only ₹20 crore in loans and no debentures or public deposits has an aggregate of just ₹20 crore for this threshold—well below the ₹50 crore limit. This distinction ensures the threshold captures companies with significant external financing rather than those with large operational liabilities in the normal course of business.

Annual evaluation and compliance timing

Unlisted public companies must evaluate these thresholds annually upon finalization of audited financial statements. If a company crosses any threshold for the first time, it must appoint the required independent directors at the earliest, but not later than the immediate next board meeting or within three months from the date the threshold is crossed, whichever is later. This provides a reasonable compliance window while preventing indefinite delays. Companies operating near any threshold should proactively assess whether upcoming transactions—like a major capital raise, significant loan drawdown, or exceptional revenue contract—will trigger compliance obligations, allowing time for identifying, evaluating, and appointing suitable independent directors.

Do private companies ever need independent directors?

Private limited companies generally do not face mandatory independent director requirements under the Companies Act, 2013. The independent director provisions in Section 149 and Rule 4 specifically apply to listed public companies and unlisted public companies meeting prescribed thresholds.

Private companies—whether private limited companies or one-person companies—are excluded from these requirements because they have restrictions on share transferability and typically involve closer relationships between shareholders and management, reducing the governance concerns that independent directors address.

Private companies that voluntarily choose to adopt higher governance standards sometimes appoint independent directors even without legal obligation. This is particularly common among venture capital or private equity-backed startups where investors negotiate board composition rights, often including independent director appointments to protect investor interests.

Family-owned private companies transitioning toward institutional ownership or planning eventual public listings may also voluntarily appoint independent directors to establish governance frameworks proactively. While not legally required, these voluntary appointments can strengthen corporate credibility and prepare the organization for future growth or listing.

Private companies should note that if they convert to public companies through legal restructuring, they immediately become subject to public company provisions.

If the newly converted public company meets any of the three financial thresholds (₹10 crore paid-up capital, ₹100 crore turnover, or ₹50 crore aggregate borrowings), it must appoint at least two independent directors. Companies planning such conversions—often in preparation for external fundraising or eventual IPOs—should anticipate this requirement and begin identifying suitable independent directors before conversion to ensure seamless compliance.

How do the rules apply to government companies and PSUs?

Government companies and public sector undertakings (PSUs) are governed by a dual framework for independent director appointments—combining the Companies Act, 2013 with the Department of Public Enterprises (DPE) Guidelines on Corporate Governance for CPSEs (2010) and related circulars of the Ministry of Corporate Affairs.

Under Section 2(45) of the Companies Act, a government company is one in which not less than 51 per cent of paid-up share capital is held by the Central Government, State Government(s), or both. Such companies are required to appoint independent directors if they fall within the general applicability thresholds prescribed under Section 149(4) and Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014—unless exempted (for instance, wholly-owned government companies).

For listed PSUs, Section 149(4) of the Companies Act and Regulation 17(1)(b) of SEBI (LODR) Regulations, 2015 mandate that one-third of the board comprise independent directors. Where the chairman is an executive director or related to the promoter, the proportion increases to at least one-half. The DPE’s 2010 Guidelines (para 3.1.4) reiterate this principle:

“In a CPSE listed on the Stock Exchange with an executive chairman, at least 50 per cent of the board shall comprise independent directors; and in other CPSEs (listed without an executive chairman or unlisted CPSEs), at least one-third of the board members shall be independent directors.”

Unlisted government companies and PSUs must evaluate their status against the three financial thresholds just like unlisted private sector public companies. Given that most PSUs operate at significant scale, many exceed at least one threshold (particularly the ₹100 crore turnover or ₹50 crore borrowing thresholds) and therefore require at least two independent directors. The Department of Public Enterprises issues additional guidelines that sometimes prescribe higher corporate governance standards for Central PSUs, including recommendations for greater board independence beyond the statutory minimum.

One key distinction for government companies relates to the definition of “independent director” under Section 149(6). The independence criteria exclude persons related to promoters, and since the government is the promoter in government companies, government officials actively involved in the ministry or department overseeing the PSU cannot qualify as independent directors. However, retired civil servants, former government employees, and officials from unrelated government departments may qualify as independent directors if they meet all other independence criteria, particularly the requirement that they not have held key managerial positions in the company in the preceding three financial years.

Are startups or small companies required to appoint independent directors?

Startups and small companies face independent director requirements only if they meet specific criteria—there is no blanket exemption or special relaxation for entities recognized as startups under the Startup India initiative or companies below certain size thresholds. The applicability determination depends entirely on whether the startup or small company is structured as a private limited company (generally exempt) or public limited company (subject to threshold evaluation), and whether it has listed securities (mandatory requirement regardless of size).

Most startups incorporate as private limited companies, which exempts them from mandatory independent director requirements under current regulations.

A technology startup structured as “XYZ Technologies Private Limited” with ₹50 crore paid-up capital and ₹200 crore annual turnover has no legal obligation to appoint independent directors under the Companies Act. However, if that same startup converts to a public limited company as “XYZ Technologies Limited” (which sometimes occurs during fundraising from institutional investors who prefer public company structures), it immediately becomes subject to the unlisted public company thresholds. With ₹50 crore paid-up capital (exceeding the ₹10 crore threshold), ₹200 crore turnover (exceeding the ₹100 crore threshold), and likely significant borrowings, the company would require at least two independent directors immediately upon conversion.

Startups planning initial public offerings must appoint independent directors before listing to comply with the one-third board composition requirement applicable to all listed companies. IPO-bound startups typically begin restructuring their boards 12-18 months before filing draft prospectuses, appointing independent directors who can provide governance oversight during the pre-IPO audit period and lend credibility to the offering. The presence of reputable independent directors on startup boards often positively influences investor perception during IPOs, making early appointment strategically valuable beyond mere compliance.

Venture capital and private equity investors frequently require independent director appointments through shareholders’ agreements even when not legally mandated. An investor might negotiate the right to appoint one independent director as a term of investment, or require that the startup maintain at least two independent directors to ensure governance oversight of management. While these are contractual obligations rather than statutory requirements, startups accepting such investments must comply with independent director provisions even as private limited companies. The independent directors in such cases play crucial roles in audit committees, reviewing related-party transactions, and overseeing management performance on behalf of minority investors.

Small companies as defined under Section 2(85) of the Companies Act—companies with paid-up capital not exceeding ₹4 Crore and turnover not exceeding ₹40 crore—generally do not meet any of the three threshold criteria for unlisted public companies. However, the small company definition provides various procedural relaxations and compliance exemptions across different provisions of the Companies Act, but it does not create a specific exemption from independent director requirements. If a small company is a public limited company that happens to meet any threshold (most unlikely given the ₹4 crore capital and ₹40 crore turnover caps, but possible if it has significant borrowings exceeding ₹50 crore), it must appoint independent directors despite its small company status.

What about foreign subsidiaries and wholly-owned subsidiaries operating in India?

Foreign subsidiaries and wholly-owned subsidiaries operating in India present unique scenarios for independent director applicability. The determining factors include how the entity is incorporated (Indian company vs. foreign company with Indian operations), whether it is a wholly-owned subsidiary (100% owned by another company) or majority-owned subsidiary, and whether the parent company is listed or unlisted. Each permutation creates different compliance obligations under the Companies Act and SEBI regulations.

Wholly-Owned indian subsidiaries of foreign companies

When a foreign company establishes a wholly-owned subsidiary in India (for example, “ABC India Private Limited” owned 100% by “ABC Corporation USA”), the subsidiary is an Indian company subject to the Companies Act. If structured as a private limited company, it generally has no independent director requirement regardless of size. If structured as a public limited company, Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 provides explicit exemption—wholly-owned subsidiaries are not required to appoint independent directors even when they meet the financial thresholds of ₹10 crore paid-up capital, ₹100 crore turnover, or ₹50 crore borrowings.

This exemption recognizes that wholly-owned subsidiaries operate under complete control of their parent companies, and the independent director requirement for the parent company (if it is an Indian listed or qualifying unlisted public company) provides sufficient governance oversight across the group. However, the exemption applies only to wholly-owned subsidiaries—if the parent owns 99.9% with 0.1% held by another entity or individual, the subsidiary does not qualify for exemption and must appoint independent directors if it meets any threshold as an unlisted public company.

Listed subsidiaries of indian or foreign companies

If a subsidiary company itself lists its shares on Indian stock exchanges (even if majority-owned by a parent), the subsidiary becomes subject to the mandatory one-third independent director requirement under Section 149(4) and SEBI LODR Regulation 17. The wholly-owned subsidiary exemption does not apply to listed entities under any circumstances. Additionally, Regulation 24 of SEBI LODR requires that at least one independent director on the board of a listed parent company must also be a director on the board of a material unlisted subsidiary, creating an additional governance linkage requirement for subsidiary oversight.

Indian subsidiaries of listed indian parent companies

When an Indian listed company owns a subsidiary (whether wholly-owned or majority-owned), the subsidiary’s independent director obligations depend on its own characteristics. A wholly-owned subsidiary benefits from the exemption in Rule 4 and need not appoint independent directors even if it exceeds financial thresholds. However, if the subsidiary has minority shareholders (not wholly-owned) and meets any of the three thresholds as an unlisted public company, it must appoint at least two independent directors. The parent company’s listed status does not automatically exempt the subsidiary from independent director requirements—each entity is evaluated independently for compliance.

Foreign companies operating in India

Foreign companies operating in India through branch offices or liaison offices are not considered Indian companies incorporated under the Companies Act and therefore are not subject to Indian independent director requirements. These entities follow governance norms of their home jurisdiction. However, if a foreign company establishes a Section 8 company (non-profit organization), or incorporates an Indian subsidiary company, that Indian entity becomes fully subject to the Companies Act including independent director provisions based on company type and applicable thresholds. The distinction between operating through branch offices (not subject to Indian independent director rules) versus incorporated subsidiaries (fully subject to Indian law) is critical for multinational corporations planning their Indian presence.

Independent director applicability under Companies Act 2013 vs SEBI LODR Regulations 2015

Listed companies in India operate under a dual regulatory framework where the Companies Act, 2013 establishes foundational corporate governance requirements while SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 impose additional market-facing obligations.

Understanding how these frameworks differ in their approach to independent director applicability is crucial because listed entities must comply with the stricter requirement when provisions diverge.

While both frameworks share the goal of strengthening board independence and protecting stakeholder interests, they differ significantly in minimum board composition ratios, maximum directorship limits, tenure restrictions, and special provisions for high-profile listed entities.

What are the differences in minimum board composition ratios?

The Companies Act and SEBI LODR establish similar baseline board composition requirements but diverge significantly in specific situations involving executive leadership structures.

Section 149(4) of the Companies Act requires that every listed public company have at least one-third of its total directors as independent directors, with any fraction rounded up to one. SEBI LODR Regulation 17(1)(b) mirrors this requirement, stipulating that the board of a listed entity shall have at least one-half of the board comprising independent directors when the chairperson is an executive director or is related to the promoter or persons occupying management positions.

How do maximum directorship and tenure limits differ?

Maximum directorship limits for independent directors represent a critical difference between the Companies Act and SEBI LODR frameworks.

The Companies Act establishes general directorship limits under Section 165, allowing a person to be appointed as director in a maximum of twenty companies, with a sub-limit of ten public companies. However, this section does not create a specific limit on the number of companies where one can serve as an independent director.

In contrast, SEBI LODR Regulation 17A imposes a precise restriction: a person cannot serve as an independent director in more than seven listed entities simultaneously.

This seven-listed-entity limit operates independently of the Companies Act’s twenty-company limit, meaning an individual could theoretically be a director in twenty companies total but serve as an independent director in only seven of those if they are listed entities.

The restriction becomes more stringent for individuals who are whole-time directors (including managing directors or executive directors) in any listed company—such persons can serve as independent directors in not more than three listed entities. This provision prevents executive leaders from spreading their attention too thin across multiple independent director roles while maintaining demanding executive responsibilities in their primary employment.

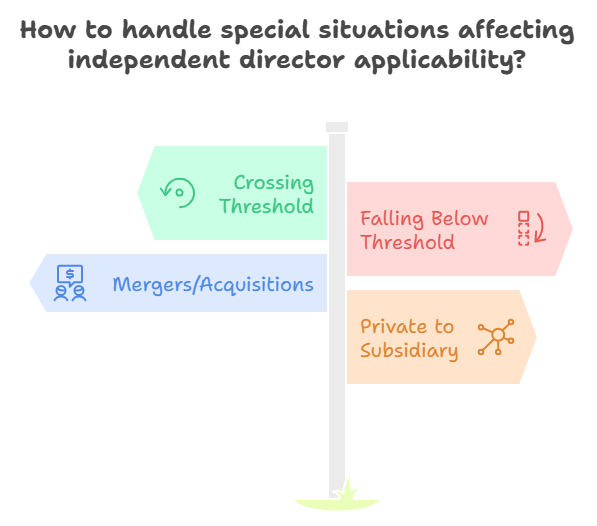

Special situations affecting independent director applicability

Corporate structures and circumstances rarely remain static—companies cross regulatory thresholds through organic growth, fall below thresholds during business downturns, undergo mergers and acquisitions that reshape their legal structure, and navigate transitions between private and public company status.

Understanding these edge cases is essential for proactive compliance management, particularly for companies operating near applicability thresholds or planning significant corporate actions that might trigger or eliminate independent director requirements.

What happens when a company crosses or falls below the applicability threshold?

When an unlisted public company crosses any of the three financial thresholds for the first time—exceeding ₹10 crore paid-up share capital, ₹100 crore turnover, or ₹50 crore aggregate borrowings—the independent director requirement triggers immediately upon finalization of the audited financial statements confirming the threshold breach. The company must appoint the required minimum two independent directors at the earliest, but not later than the immediate next board meeting or within three months from the date of crossing the threshold, whichever is later, as stipulated in Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014. For practical purposes, the “date of crossing” is typically the balance sheet date when the threshold was exceeded, not the date when audited financials were actually signed.

The three-month compliance window provides companies reasonable time to identify suitable independent director candidates, conduct due diligence on their qualifications and independence, obtain their consent, convene board and shareholder meetings for appointment approval, and complete MCA filings. Companies approaching thresholds should monitor their financial position quarterly and begin identifying potential independent directors proactively when threshold breach appears likely, rather than waiting until audited financials confirm the requirement.

How do mergers, acquisitions, or restructurings impact compliance?

Mergers, acquisitions, and corporate restructurings create complex independent director applicability scenarios because these transactions fundamentally alter company structures, combining previously separate entities or splitting single entities into multiple companies. Under the Companies Act, mergers and amalgamations approved by the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) result in the dissolution of the transferor company and the transferee company absorbing all assets, liabilities, and obligations. The board composition of the transferor company ceases to exist, and the surviving company’s board composition determines independent director obligations based on the post-merger entity’s characteristics.

If an unlisted public company that does not meet independent director thresholds merges with another unlisted public company, and the combined entity exceeds any threshold (for example, if Company A with ₹8 crore paid-up capital merges with Company B having ₹5 crore paid-up capital, creating a merged entity with ₹13 crore paid-up capital), the merged entity must appoint independent directors within the three-month window from the effective date of merger. Similarly, if a private limited company is amalgamated with a public limited company and the merged entity is structured as a public company meeting thresholds, independent director requirements apply immediately post-merger.

What if a private company becomes a subsidiary of a public company?

When a private limited company becomes a subsidiary of a public limited company—whether through acquisition, conversion, or restructuring—the private subsidiary’s independent director obligations depend entirely on its own characteristics, not those of its public parent. If the private subsidiary remains structured as a private limited company after becoming a subsidiary, it continues to be exempt from independent director requirements regardless of the parent’s status, size, or listing. The Companies Act evaluates each company’s compliance obligations independently based on that company’s incorporation type and financial thresholds.

However, two scenarios can trigger independent director requirements for a private subsidiary.

First, if the parent company requires the private subsidiary to convert to a public limited company as part of post-acquisition integration or corporate structure rationalization, the converted entity immediately becomes subject to public company provisions. If the newly converted public subsidiary meets any of the three financial thresholds, it must appoint at least two independent directors within three months.

Second, if the parent company is a listed entity and the subsidiary exceeds the materiality threshold defined in SEBI LODR Regulation 16(1)(c) —where the subsidiary’s income or net worth exceeds 10% of the listed parent’s consolidated financials—the listed parent must ensure that at least one independent director from its own board serves on the material subsidiary’s board.

Within how much time must new independent directors be appointed after the applicability triggers?

The Companies Act and rules establish specific timelines for appointing independent directors once the requirement arises, though these timelines vary slightly depending on the triggering event. For unlisted public companies crossing financial thresholds for the first time, Rule 4 mandates appointment “at the earliest” but grants a maximum window of the immediate next board meeting or three months from the date the threshold was crossed, whichever is later. If a company’s audited financial statements finalized on August 15, 2025, confirm that it crossed the ₹10 crore paid-up capital threshold as of March 31, 2025, the company must appoint independent directors by November 15, 2025 (three months from the triggering event).

For listed companies and other scenarios involving intermittent vacancies—when an existing independent director resigns or is removed—the timeline is more stringent. Rule 4 specifies that any intermittent vacancy shall be filled “at the earliest” but not later than the immediate next board meeting or three months from the date of vacancy, whichever is later.

Consequences of Non-Compliance With Independent Director Requirements

Non-compliance with independent director requirements carries serious legal, financial, and reputational consequences for companies and their officers. The regulatory framework establishes penalties that extend beyond monetary fines to include director disqualification, potential invalidation of board decisions taken without proper composition, and adverse impacts on listed company standing with stock exchanges. Understanding these consequences is essential for boards and management teams to prioritize compliance, particularly when facing operational pressures or challenges in identifying suitable independent director candidates.

What are the consequences of non-compliance with independent director requirements?

If a company required to appoint independent directors under Section 149(4) fails to do so, it amounts to a contravention of the provisions of Chapter XI of the Companies Act, 2013. Under Section 172, such non-compliance attracts a monetary penalty — the company and every officer in default are liable to a fine of not less than ₹50,000 and which may extend to ₹5 lakh.

While Section 454 of the Act empowers the Registrar or adjudicating officer to levy such penalties, it does not provide for imprisonment. Thus, the non-appointment of independent directors primarily leads to financial penalties rather than criminal prosecution, though it can have reputational and regulatory consequences (e.g., SEBI action for listed entities).

Are there penalties beyond monetary fines — e.g., invalid board decisions or disqualification risks?

Beyond direct monetary penalties, non-compliance creates several additional legal risks. Board resolutions passed when the board composition violates statutory requirements may be challenged as void or voidable, particularly resolutions concerning material transactions like related-party dealings, major asset sales, or fund raising that specifically require independent director approval or oversight through audit committees.

While Indian courts have not universally held all decisions of non-compliant boards void, the legal uncertainty creates risk for third parties transacting with the company and may lead to disputes regarding the enforceability of contracts approved by defectively constituted boards.

Conclusion

Independent director applicability in India follows a carefully structured regulatory framework designed to enhance corporate governance without imposing undue compliance burdens on smaller companies or closely-held private entities. Listed public companies face mandatory requirements automatically upon listing, needing at least one-third independent directors with enhanced requirements when executive chairpersons have promoter relationships. Unlisted public companies must evaluate three distinct financial thresholds annually—₹10 crore paid-up capital, ₹100 crore turnover, or ₹50 crore aggregate borrowings—and appoint minimum two independent directors when meeting any threshold, unless qualifying for exemptions as wholly-owned subsidiaries, joint ventures, or dormant companies.

The dual regulatory framework requiring compliance with both the Companies Act, 2013 and SEBI LODR Regulations, 2015 for listed entities creates complexity but ultimately strengthens investor protection and market confidence. Companies must navigate special situations like threshold crossings, mergers and restructurings, and subsidiary relationships carefully, with clear compliance timelines requiring appointment within three months of triggering events. Non-compliance carries significant consequences including fines up to ₹5 lakh for companies, personal penalties for officers in default, and potential disqualification risks. Whether you’re a company secretary ensuring regulatory compliance, a CFO planning corporate actions that might trigger requirements, or a board evaluating governance structures, understanding these applicability rules enables proactive compliance and helps build sustainable governance frameworks that benefit all stakeholders.

If you’re planning to qualify and serve as one, here’s a step-by-step guide on How to Become an Independent Director — covering eligibility, databank registration, and appointment process.

Frequently Asked Questions About Independent Director Applicability

Do all companies in India need to appoint independent directors?

No, not all companies in India need independent directors. Listed public companies must appoint them mandatorily regardless of size. Unlisted public companies need them only if meeting specific financial thresholds. Private limited companies generally don’t require independent directors.

What is the minimum number of independent directors required?

Listed public companies need at least one-third of their board as independent directors. Unlisted public companies meeting thresholds need a minimum of two independent directors. If the chairman of a listed company is an executive director related to promoters, at least half the board must be independent.

Are private limited companies required to have independent directors?

Private limited companies generally do not need independent directors under the Companies Act, 2013. However, they may be required if subject to specific governance regulations, or if investors require them through shareholders’ agreements, or if they voluntarily choose to adopt higher governance standards.

How do I calculate if my unlisted public company meets the threshold?

Check your last audited financial statements for three criteria: (1) paid-up share capital ≥₹10 crore, (2) turnover ≥₹100 crore, or (3) aggregate outstanding loans + debentures + deposits ≥₹50 crore. Meeting any one threshold requires appointing two independent directors.

What happens if my company crosses the ₹10 crore paid-up capital threshold mid-year?

The requirement triggers when audited financial statements confirm the threshold breach. You must appoint independent directors at the earliest, but not later than the next board meeting or within three months from the balance sheet date showing the threshold was exceeded, whichever is later.

Are foreign subsidiaries operating in India subject to independent director requirements?

Foreign subsidiaries incorporated in India as Indian companies follow the same rules as domestic companies—private subsidiaries generally exempt, public subsidiaries evaluated based on thresholds. Wholly-owned subsidiaries are specifically exempted even if meeting thresholds. Foreign companies operating through branch offices are not subject to Indian independent director rules.

Can a wholly-owned subsidiary avoid appointing independent directors?

Yes, Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 specifically exempts wholly-owned subsidiaries from independent director requirements even when they exceed financial thresholds. However, this exemption does not apply if the subsidiary itself lists its shares.

What is the difference between Companies Act and SEBI requirements for listed companies?

Both require one-third independent directors baseline, but SEBI LODR increases this to half when the chairperson is an executive director related to promoters. SEBI limits independent directors to seven listed entity directorships, while Companies Act has no specific independent director limit. Both must be satisfied by listed companies.

How many listed companies can one person serve as an independent director?

Under SEBI LODR Regulation 17A, a person cannot serve as independent director in more than seven listed entities. If the person is a whole-time director in any listed company, the limit reduces to three listed entities for independent directorships.

What is the penalty for not appointing independent directors when required?

If a company required to appoint independent directors under Section 149(4) fails to do so, it amounts to a contravention of the provisions of Chapter XI of the Companies Act, 2013. Under Section 172, such non-compliance attracts a monetary penalty — the company and every officer in default are liable to a fine of not less than ₹50,000 and which may extend to ₹5 lakh.

Do dormant companies need independent directors?

No, Rule 4 specifically exempts dormant companies (defined under Section 455) from independent director requirements even if they meet financial thresholds. This recognizes that dormant companies conduct no business operations and don’t present governance concerns independent directors address.

When does the three consecutive years exemption rule apply?

If an unlisted public company that previously required independent directors ceases to meet all three financial thresholds for three consecutive financial years, it is no longer required to maintain independent directors until it again meets any threshold. The requirement doesn’t end after just one year below thresholds.

Is the appointment of independent directors mandatory for startups?

Startups structured as private limited companies have no mandatory independent director requirement regardless of size. If structured as public limited companies and meeting thresholds, they must appoint two independent directors. Startups planning IPOs must appoint one-third independent directors before listing.

What forms need to be filed with MCA after appointing independent directors?

Companies must file Form DIR-12 within 30 days of the board resolution appointing independent directors. Independent directors must provide consent in Form DIR-2 and disclosure in Form DIR-8. Listed companies must also disclose appointments to stock exchanges within 24 hours under SEBI LODR.

How soon must independent directors be appointed after the requirement arises?

Independent directors must be appointed at the earliest, but not later than the immediate next board meeting or three months from when the requirement arose, whichever is later.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications